Abstract

Purpose

Endotracheal intubation (ETI) of critically ill patients is a high-risk procedure that is commonly performed by resident physicians. Multiple attempts (≥2) at intubation have previously been shown to be associated with severe complications. Our goal was to determine the association between year of training, type of residency, and multiple attempts at ETI.

Methods

This was a cohort study of 191 critically ill patients requiring urgent intubation at two tertiary care teaching hospitals in Vancouver, Canada. Multivariable logistic regression was used to model the association between postgraduate year (PGY) of training and multiple attempts at ETI.

Results

The majority of ETIs were performed for respiratory failure (68.6%) from the hours of 07:00–19:00 (60.7%). Expert supervision was present for 78.5% of the intubations. Multiple attempts at ETI were required in 62%, 48%, and 34% of patients whose initial attempt was performed by PGY-1, PGY-2, and PGY-3 non-anesthesiology residents, respectively. Anesthesiology residents required multiple attempts at ETI in 15% of patients, regardless of the year of training. The multivariable model showed that both higher year of training (risk ratio [RR] 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.54-0.93; P < 0.01) and residency training in anesthesiology (RR 0.52; 95% CI 0.20-1.0; P = 0.05) were independently associated with a decreased risk of multiple intubation attempts. Finally, intubations performed at night were associated with an increased risk of multiple intubation attempts (RR 1.3; 95% CI 1.0-1.4; P = 0.03).

Conclusion

Year of training, type of residency, and time of day were significantly associated with multiple tracheal intubation attempts in the critical care setting.

Résumé

Objectif

L’intubation endotrachéale (IET) des patients en phase critique est une intervention à haut risque qui est souvent réalisée par les médecins résidents. Il a été démontré par le passé que des tentatives multiples (≥2) d’intubation étaient associées à des complications graves. Notre objectif était de déterminer l’association entre l’année de formation, le type de résidence et les tentatives multiples d’IET.

Méthode

Cette étude de cohorte a examiné 191 patients en phase critique nécessitant une intubation d’urgence dans deux hôpitaux universitaires de soins tertiaires à Vancouver, au Canada. Une méthode de régression logistique multivariée a été utilisée pour illustrer l’association entre l’année de résidence (R) et les tentatives multiples d’IET.

Résultats

La plupart des IET ont été réalisées en raison d’insuffisance respiratoire (68,6 %) entre 7 h et 19 h (60,7 %). La supervision par un expert était disponible dans 78,5 % des cas d’intubation. Plusieurs tentatives d’IET ont été nécessaires chez 62 %, 48 % et 34 % des patients chez lesquels la première tentative avait été réalisée par un résident R1, R2 et R3, respectivement, dont la discipline était autre que l’anesthésiologie. Les résidents en anesthésiologie ont nécessité plusieurs tentatives d’IET chez 15 % des patients, indépendamment du nombre d’années de formation. Le modèle multivarié a montré qu’une année de formation plus élevée (risque relatif [RR] 0,74; intervalle de confiance 95 % [IC] 0,54-0,93; P < 0,01) et une résidence en anesthésiologie (RR 0,52; IC 95 % 0,20-1,0; P = 0,05) étaient indépendamment associées à un risque réduit de tentatives d’intubation multiples. Enfin, les intubations réalisées pendant la nuit étaient associées à un risque accru d’intubations multiples (RR 1,3; IC 95 % 1,0-1,4; P = 0,03).

Conclusion

L’année de formation, le type de résidence et le moment de la journée sont trois facteurs qui ont été associés de manière significative à des tentatives multiples d’intubation trachéale dans un contexte de soins critiques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Day-to-day care of patients in academic intensive care units (ICUs) is often provided by postgraduate physicians-in-training (residents) who are under the supervision of attending physicians. Residents provide a range of clinical services in the ICU, including life-saving medical procedures that may be associated with a high risk of complications. One such procedure is endotracheal intubation (ETI). In the operating theatre, ETI is generally performed in controlled circumstances by anesthesiologists and carries a low risk of complications.1 In contrast, ETI in the ICU is often performed under suboptimal conditions, in patients who have limited physiologic reserve, and by individuals who may have variable levels of expertise in airway management. Up to 54% of critically ill patients who undergo ETI may experience a complication.2 Even in ICUs where the majority of intubations are performed by highly skilled individuals (experienced anesthesiology residents or staff intensivists), severe life-threatening complications have been reported in 28% of cases.3

At our institution and in many similar teaching hospitals, many ETIs in critically ill patients are performed by resident physicians who do not have formal training in anesthesiology. Under these conditions, we have found that 39% of ETIs are associated with complications, including severe hypoxemia (19.1%), severe hypotension (9.6%), esophageal intubation (7.4%), and aspiration of gastric contents (5.9%).4 Furthermore, if multiple (≥2) attempts at ETI are required to successfully intubate the patient’s trachea, there is a three-fold increased risk of severe complications, including hypotension and hypoxemia.4 We hypothesized that a lower postgraduate year (PGY) of training and being in a non-anesthesiology residency program are associated with multiple attempts at ETI. The purpose of this study was to assess the extent to which the type and level of training of the resident physician are associated with successful outcomes during ETI.

Methods

The protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver General Hospital, and St. Paul’s Hospital. This was a cohort study of critically ill patients requiring ETI. Information was collected regarding ETIs performed in the ICUs at two tertiary care teaching hospitals affiliated with the University of British Columbia from January 1, 2008 to October 30, 2008. The ICUs at Vancouver General Hospital (27 beds) and St. Paul’s Hospital (15 beds) are both “closed” mixed medical-surgical units; most patients in these units have a 1:1 nurse to patient ratio. The ICUs are managed by board-certified intensivists who have backgrounds in anesthesiology, emergency medicine, internal medicine, or general surgery. The ICUs are also staffed by first, second, and third year residents from varying programs and by an ICU fellow. The ICU fellowship is a postgraduate program of the Royal College of Physicians & Surgeons of Canada, and admission requires near completion of specialty training in internal medicine, emergency medicine, general or cardiac surgery, or anesthesiology. Within each ICU, there are two separate teams consisting of at least one junior (PGY-1) and two to four senior (PGY-2 & 3) residents, an ICU attending, and a fellow. Residents rotating through the ICU attend to hospital resuscitations. This “code-blue” team consists of two senior residents (PGY-2 and above) or clinical associates, respiratory therapists, and nurses. The resuscitations that occur during the day (07:00-19:00 hr) are attended by the ICU attending or fellow. They are not on site at night and thus not immediately available (must be within 15 min). There is an on-site anesthesiologist who will attend if there are any anticipated or real problems in airway management. At Vancouver General Hospital, there are two clinical associates (experienced hospitalist physicians who assist the rotating residents) who each have been working in the ICU for more than five years. Clinical associates at St. Paul’s Hospital are residents who have already completed their senior ICU rotation and who work only when there is an insufficient number of residents on call. All clinical associates are on site and are part of the “code-blue” team.

Procedure and data collection

At the beginning of their ICU rotation, the residents receive a lecture on airway management from the attending physician or clinical fellow. The ICU team is responsible for intubations in the ICU as well as for attending to hospital resuscitations outside of the emergency department, operating theatres, and cardiac surgery ICU. The majority of intubations are supervised by the attending staff, ICU fellows, non-intensivist anesthesiologists, or clinical associates. Medications are not standardized and are administered at the discretion of the physicians. After each ETI performed during the study period, the intubating physician completed a standardized web-based data collection form consisting of intubating physician, patient, and procedural information. This web-based form has been used routinely since January 2008 to collect information on intubations in both ICUs. The following data were recorded: year-of-training and residency program of the primary operator, level and specialty of the supervisor (if present during the intubation), indication and location of ETI, equipment used (including type of laryngoscope and blade, end-tidal CO2 detectors, and medications), use of cricoid pressure (to prevent gastric aspiration), vital signs before the ETI, lowest arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) during each intubation attempt, and vital signs after the procedure (at five and 30 min). Airway physical examination (Mallampati score,5 mouth opening,6 thyromental distance,7 and neck extension),6 Cormack-Lehane grade,8 and duration of each attempt at intubation were recorded. We defined an attempt as inserting the laryngoscope into the mouth. Any repositioning or suctioning while maintaining the laryngoscope in position would be counted as a single attempt. Chest radiographs were obtained after all ETIs (part of our daily practice), and demographics, length of stay, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II scores, and mortality data were obtained from our ICU database. The ETIs we included in our analysis were only those where the initial attempt was performed by a resident.

Statistical considerations

All analyses were completed using Stata 10.0 (StataCorp. 2007, Stata Statistical Software: Release 10, College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LP). Fisher’s exact testing for categorical data and independent t tests for normally distributed continuous data were used for univariate analyses. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare number of ICU days between the three groups (PGY-1, PGY-2, and PGY-3). A complete-case analysis was performed. All tests were two-sided. We considered a P value < 0.05 level to be statistically significant.

Assuming ten outcome events would be required per covariate of interest in the final model, we required approximately 80 outcome events. Based on our prior study,4 multiple ETI attempts by non-experts would be required in approximately 40% of intubations. Thus, a total sample of 200 patients would be required. This number was increased to account for repeated tracheal intubation attempts in the same patient and for potential missing data.

Multivariable logistic regression was used to model the association between postgraduate year of training and multiple attempts at ETI (two or more attempts). The following covariates included in the final model were selected a priori based on their potential to confound the exposure outcome relationship: anesthesiology residency program (vs other programs); examination suggestive of difficult intubation (Mallampati grade III or IV, or thyromental distance <2 cm, or mouth opening ≤2 cm), APACHE II score, age of patient, use of neuromuscular blockers, hospital, and presence of a supervisor. Using univariate logistic regression, linearity in the log-odds of continuous covariates was assessed visually and by comparing the linear with a categorical model (using indicator variables with bins of equal widths) by likelihood ratio testing. This approach resulted in a P value of 0.76 for year-of-training, indicating that the linear trend model fit the data adequately. Given the high prevalence of our outcome, we applied a correction to approximate the risk ratio from the odds ratio.9 Finally, effect measure modification was assessed by using the Mantel-Haenzel test of homogeneity.

Results

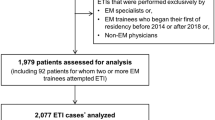

During the study period, data were collected for 275 ETIs. Fifty-two patients received more than one ETI during the study period, and only their first intubation was included in the analysis. Also excluded were 20 intubations where the first attempt was performed by clinical fellows, clinical associates, or attending physicians and 12 intubations for which there were missing data. Thus, the total cohort analyzed was 191 intubations. There were no deaths recorded during the procedures, although one patient required a surgical airway after two failed attempts at direct laryngoscopy.

The mean age in our cohort was 61.2 years; 37.7% were female, and the mean APACHE II score was 23.5 (Table 1). The majority of ETIs were performed in the ICU (61.8%). The most common reason for ETI was respiratory failure (68.6%), with 61% of all intubations occurring from 07:00–19:00 hr.

Overall, 13.6% of residents were in an anesthesiology training program (Table 2). Supervisors were present for 78.5% of the ETIs, but there was less supervision of primary operators who were more senior in their training (P = 0.06). Supervisors consisted of ICU fellows (40%), ICU attendings (20%), non-intensivist anesthesiologists (17%), and clinical associates (16%). Data were missing on supervisor background in 7% of intubations. Direct laryngoscopy was used for the first attempt in 93.2% of ETIs, regardless of the year of training (P = 0.91). Fifty-two percent of patients had at least one physical examination finding suggestive of a potentially difficult tracheal intubation. There was less use of cricoid pressure by residents in the third year of training (P = 0.04). There was no effect modification on the relationship of third year residents and use of cricoid due to the presence of a supervisor (test of homogeneity P = 0.38). There was no relationship between year of residency training and either ICU length of stay (P = 0.65) or patient mortality (P = 0.27).

Overall, multiple attempts at ETI were required by 62% of PGY-1, 44% of PGY-2, and 30% of PGY-3 residents. After excluding anesthesiology residents, this relationship persisted with multiple attempts at ETI required by 62% of PGY-1, 48% of PGY-2, and 34% of PGY-3 non-anesthesiology residents. PGY-2 or PGY-3 anesthesiology residents required multiple attempts in 15% of ETIs regardless of the year of training. Univariate logistic regression model testing for trend demonstrated that each higher year of training was associated with a 26% decreased risk of multiple intubation attempts (risk ratio [RR] 0.74; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.58-0.91; P < 0.01). The final multivariable logistic regression model is presented in Table 3. There was no substantive change in the point estimate for year of training after adjustment for covariates (RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.54-0.93; P < 0.01). In addition, residency training in anesthesiology was associated with a decreased risk of multiple attempts at intubation (RR 0.52; 95% CI 0.20-1.0; P = 0.05). Finally, intubations performed at night (RR 1.3; 95% CI 1.0-1.4; P = 0.03) and any physical examination finding suggestive of difficult laryngoscopy (RR 1.4; 95% CI 1.2-1.5; P < 0.01) were both associated with an increased risk of multiple attempts at intubation.

Discussion

In our study, we found that each additional postgraduate year of training and a residency training program in anesthesiology were associated with a decreased risk of multiple attempts at ETI in critically ill patients. In addition, intubations performed at night (19:00-07:00 hr) were associated with an increased risk of multiple intubation attempts. Although not examined in the current study, multiple attempts at ETI have previously been shown to be associated with airway-related10 and severe cardiopulmonary complications.4 Our results for centres that have non-anesthesiology residents performing ETI in critically ill patients raise questions regarding the appropriate clinician to perform tracheal intubations in this patient population.

Although our group has previously found that non-expert operators required significantly more attempts than “experts” to intubate the trachea, there was no difference in complications between the two groups.4 However, in that analysis, we considered intubations performed by both residents and non-residents (ICU consultants, ICU fellows, and clinical associates) and did not examine level of postgraduate training as a predictor variable. The results of the current study add to this existing literature by specifically exploring the impact of year of training and success at ETI in an adult population of critically ill patients.

The mechanism by which non-anesthesiology residents improve over the course of their training remains unanswered by this study. Residents certainly accrue technical skills throughout their residency. However, non-anesthesiology residents would not be exposed to significant numbers of ETIs outside of their ICU rotation, as a rotation in anesthesiology was not a training requirement for surgery and internal medicine residents during the study period. Although emergency medicine residents have a dedicated rotation in anesthesia, they made up only 5.7% of our cohort. It may be that internal medicine residents, who make up the majority of the PGY-1 s and PGY-3 s, gain enough experience during their junior rotation to obtain a threshold of greater competency by the time they reach their senior year.

Given that a residency program in anesthesiology was associated with less risk of multiple attempts and intubation; one method to improve success may be to mandate that all ETIs in critically ill patients be performed by individuals with anesthesiology training. However, there may be limited access to such physicians in many institutions, and airway management must be provided by physicians who have various subspecialty backgrounds. Indeed, ETI remains a specific competency of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada objectives of training for internal medicine.11 Although ETI is not a specific requirement of the American Board of Internal Medicine, trainees must be competent in Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS)12 which, according to the 2005 American Heart Association Guidelines,13 includes use of an advanced airway (e.g., ETI) as a fundamental ACLS skill.

Nevertheless, given the high risk of a difficult intubation3 , 4 and limited physiologic reserve of critically ill patients,14 the need for minimizing attempts appears prudent. Although non-anesthesiology residents certainly improved with each year of training, PGY-3 s still required multiple attempts at ETI in 34% of cases vs 16% of cases for PGY-3 anesthesiology residents.

How can residents acquire the necessary technical skills to become competent and what constitutes competency? These are questions that apply not only to residency programs but also to maintenance of skills by practicing physicians. Unfortunately for ETI, there is no current uniform standard by which we define competency, and there is no specified number of procedures required to attain competency. Certainly, high-fidelity patient simulation shows promise by demonstrating that experience gained through computerized simulator training improves airway management on scenario-based respiratory arrest assessments.15 - 17 Although it remains unclear if skills acquired through simulation translate to improved clinical performance, simulation may prove to be a valuable means for less experienced operators to improve airway management skills. Finally, there are newer intubation devices, such as the Glidescope® videolaryngoscope (Verathon Medical, Bothell WA, USA) and the Airtraq® optical laryngoscope (Prodol Ltd, Vizcaya, Spain) that are associated with improved laryngoscopic views compared with direct laryngoscopy.18-20 In addition, videolaryngoscopy has recently been shown to improve intubation success of novice users in the elective operative setting.21 Further studies are required to determine the definition of ETI competency in critically ill patients and to evaluate the efficacy of these and other training modalities on the acquisition and maintenance of competency for ETI in this patient population.

Finally, intubations performed during the hours of 19:00-07:00 hr were independently associated with an increased risk of multiple attempts at intubation. Although not answered by this present study, it is consistent with studies showing increased medical errors in critical care patients by sleep-deprived residents in both simulator22 and clinical settings.23

There are several limitations with the current study. The association between complications and multiple attempts at intubation, the outcome used in our study, has only been demonstrated in two observational studies.4,10 It may be that the magnitude of this surrogate outcome is overstated. In addition, a major limitation is that all of the data are self-reported and subject to reporting and recall bias. We have attempted to minimize this bias by using standardized data collection forms that were completed immediately after ETI and by limiting the scope of our outcome data to number of attempts at ETI. In addition, the number of PGY-1 residents was very small, leading to a very imprecise estimate (i.e., wide confidence interval) for this group. However, the linear relationship that persists through all three years of residency training helps mitigate this lack of precision. Although using ten events per covariate to determine sample size helps to ensure stability around our final point estimate, it is not designed to detect meaningful clinical differences between our groups. As we considered only those intubations performed by residents, selection bias could have been introduced because potentially difficult intubations may have been performed by fellows or staff. Similarly, there may be unmeasured confounding, as supervisors may have directed ETIs that appeared to be more difficult to more senior residents. However, this likely would have introduced positive confounding (towards the null), and thus our results may be an underestimate of the true point estimate. In addition, we were unable to examine how the variability in supervision modified the success in endotracheal intubation. This would be an important variable to assess in future studies. As with all observational research, unmeasured or residual confounding remains an alternative explanation for our results. Finally, the generalizability of these findings is limited to ICUs with similarities to our study in terms of patient profiles, physician expertise, and supervision.

In conclusion, anesthesiology residents were more successful in ETI in the critical care setting than their non-anesthesiology counterparts. For non-anesthesiology residents, there was an inverse relationship between number of years of training and risk of multiple attempts at intubation. Future research should be directed towards evaluating methods to improve performance during ETI, especially by junior and non-anesthesiology residents.

References

Cheney FW, Posner KL, Lee LA, Caplan RA, Domino KB. Trends in anesthesia-related death and brain damage: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 2006; 105: 1081-6.

Reid C, Chan L, Tweeddale M. The who, where, and what of rapid sequence intubation: prospective observational study of emergency RSI outside the operating theatre. Emerg Med J 2004; 21: 296-301.

Jaber S, Amraoui J, Lefrant JY, et al. Clinical practice and risk factors for immediate complications of endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: a prospective, multiple-center study. Crit Care Med 2006; 34: 2355-61.

Griesdale DE, Bosma TL, Kurth T, Isac G, Chittock DR. Complications of endotracheal intubation in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med 2008; 34: 1835-42.

Mallampati SR, Gatt SP, Gugino LD, et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study. Can Anaesth Soc J 1985; 32: 429-34.

el-Ganzouri AR, McCarthy RJ, Tuman KJ, Tanck EN, Ivankovich AD. Preoperative airway assessment: predictive value of a multivariate risk index. Anesth Analg 1996; 82: 1197-204.

Frerk CM. Predicting difficult intubation. Anaesthesia 1991; 46: 1005-8.

Cormack RS, Lehane J. Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia 1984; 39: 1105-11.

Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA 1998; 280: 1690-1.

Mort TC. Emergency tracheal intubation: complications associated with repeated laryngoscopic attempts. Anesth Analg 2004; 99: 607-13.

Objectives of Training in Internal Medicine 2003. Available from URL: http://rcpsc.medical.org/residency/certification/objectives/intmed_e.pdf (accessed May 2010).

Policies and Procedures for Certification August 2009. Available from URL: http://www.abim.org/pdf/publications/Policies-and-Procedures-cert-August2009.pdf (accessed May 2010).

2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 7.1: Adjuncts for airway control and ventilation. Circulation 2005; 112: IV-51-7.

Mort TC. Preoxygenation in critically ill patients requiring emergency tracheal intubation. Crit Care Med 2005; 33: 2672-5.

Kory PD, Eisen LA, Adachi M, Ribaudo VA, Rosenthal ME, Mayo PH. Initial airway management skills of senior residents: simulation training compared with traditional training. Chest 2007; 132: 1927-31.

Mayo PH, Hackney JE, Mueck JT, Ribaudo V, Schneider RF. Achieving house staff competence in emergency airway management: Results of a teaching program using a computerized patient simulator. Crit Care Med 2004; 32: 2422-7.

Rosenthal ME, Adachi M, Ribaudo V, Mueck JT, Schneider RF, Mayo PH. Achieving housestaff competence in emergency airway management using scenario based simulation training: comparison of attending vs housestaff trainers. Chest 2006; 129: 1453-8.

Sun DA, Warriner CB, Parsons DG, Klein R, Umedaly HS, Moult M. The GlideScope video laryngoscope: Randomized clinical trial in 200 patients. Br J Anaesth 2005; 94: 381-4.

Cooper RM, Pacey JA, Bishop MJ, McCluskey SA. Early clinical experience with a new videolaryngoscope (GlideScope) in 728 patients. Can J Anesth 2005; 52: 191-8.

Maharaj CH, Costello JF, Higgins BD, Harte BH, Laffey JG. Learning and performance of tracheal intubation by novice personnel: a comparison of the Airtraq and Macintosh laryngoscope. Anaesthesia 2006; 61: 671-7.

Nouruzi-Sedeh P, Schumann M, Groeben H. Laryngoscopy via Macintosh blade versus GlideScope: success rate and time for endotracheal intubation in untrained medical personnel. Anesthesiology 2009; 110: 32-7.

Sharpe R, Koval V, Ronco JJ, et al. The impact of prolonged continuous wakefulness on resident clinical performance in the intensive care unit: a patient simulator study. Crit Care Med 2010; 38: 766-70.

Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, et al. Effect of reducing interns’ work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1838-48.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Ms. Shelly Fleck-McCaskill for her invaluable assistance with data acquisition. We also thank the residents, respiratory therapists and nurses at Vancouver General Hospital and St. Paul’s Hospital for their support of this project.

Funding

Dr. Ayas was funded by a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award and by an Established Clinician Scientist Award from Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute. Dr. Griesdale is supported in part by the members of the Vancouver Hospital Department of Anesthesia and through a Clinician Scientist Award from the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute.

Competing interests

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hirsch-Allen, A.J., Ayas, N., Mountain, S. et al. Influence of residency training on multiple attempts at endotracheal intubation. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 57, 823–829 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-010-9345-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-010-9345-x