Abstract

Population ageing in most western countries involves an increase in public expenditures and the risk of labour shortage. One way to meet these challenges is to retain older workers in the labour market by improving their work life. This article assesses whether quality of work life measures differ in importance for male and female workers in their retirement planning. This study applies samples of workers and retirees born in 1940 and 1945 drawn from Danish panel surveys in 1997 and 2002 and merged with longitudinal register data. Results suggest that male and female workers’ retirement plans are affected differently by various aspects of the job. Indeed, job demands lower planned retirement age, while increases in earnings, work hour satisfaction, and the opportunity to use skills on the job increase this age for men and women. Nevertheless, the impact of earnings is largest for men, and only male workers attach importance to job control and job security. These gender differences suggest, first, that men are more influenced than women by the quality of job dimensions in their retirement planning and, second, that an employer-initiated effort directed towards retaining older workers at the workplace will not necessarily be as effective for female as for male workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 2005, the labour force participation rate for men aged 50–59 years was 88.7% (OECD 2007).

In 2005, more than 218,000 60- to 66-year olds received VERP benefits corresponding to 48% of the age group (Department of Unemployment Insurance 2007).

At the moment where survey and register data were merged, register data from 2002 were not available.

Correlation coefficients are not shown but are available on request.

Further, the standard decomposition between income effect and substitution effect of earnings on retirement age is confirmed by the fact that, in general, no wealth effect is shown.

For further discussion of gender differences with respect to job control, see Blekesaune and Solem (2005).

These results are not shown but are available on request.

Information on work-related factors is obtained from the first wave for these individuals.

References

Blekesaune, M., & Solem, P. E. (2005). Working conditions and early retirement. A prospective study of retirement behavior. Research on Aging, 27(1), 3–30. doi:10.1177/0164027504271438.

Blöndal, S., & Scarpetta, S. (1999). ‘The retirement decision in OECD countries.’ OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 202. Paris: OECD.

Börsch-Supan, A. (2000). Incentive effects of social security on labour force participation: Evidence in Germany and across Europe. Journal of Public Economics, 78, 25–49. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(99)00110-3.

Christensen, B. J., & Gupta, N. D. (1994). ‘A dynamic programming model of married couples’ retirement behavior.’ CAE Working Paper No. 94-02, Cornell University.

Clark, A. E. (1997). Job satisfaction and gender: Why are women so happy at work? Labour Economics, 4(4), 341–372. doi:10.1016/S0927-5371(97)00010-9.

Clark, A. (2005a). What makes a good job? Evidence from OECD countries, p. 11–30 in Bazen, Stephen, Claudio Lucifora and Wiemer Salverda, Eds. ‘Job Quality and Employer Behaviour.’ New York.

Clark, A. (2005b). Your money or your life: Changing job quality in OECD countries. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 43(3), 377–400. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8543.2005.00361.x.

Clark, A., Oswald, A., & Warr, P. (1996). Is job satisfaction u-shaped in age? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 69, 57–81.

Dahl, S. -Å., Nilsen, Ø. A., & Vaage, K. (2003). Gender differences in early retirement behaviour. European Sociological Review, 19(2), 179–198. doi:10.1093/esr/19.2.179.

Danish Economic Council (2006). Danish Economy, Autumn 2006. Copenhagen.

Department of Unemployment Insurance (2007) http://www.arbejdsdirektoratet.dk/ (05.01.2007)

Disney, R., & Tanner, S. (1999). What can we learn from retirement expectation data? The Institute for Fiscal Studies, Working Paper Series No. W99/17.

Dwyer, D. S., & Hu, J. (1998). Retirement expectations and realizations: The role of health shocks and economic factors. Pension Research Council Working Paper 98-18, Wharton School Pension Research Council, University of Pennsylvania.

Elovainio, M., Forma, P., Kivimäki, M., Sinervo, T., Sutinen, R., & Laine, M. (2005). Job demands and job control as correlates of early retirement thoughts in Finnish social and health care employees. Work and Stress, 19(1), 84–92. doi:10.1080/02678370500084623.

Filer, R. K., & Petri, P. A. (1988). A job-characteristics theory of retirement. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 70(1), 123–128. doi:10.2307/1928158.

Freeman, R. B. (1978). Job satisfaction as an economic variable. The American Economic Review, 68(2), 135–141. Papers and Proceedings of the Ninetieth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association.

Friedberg, L. (2003). The impact of technological change on older workers: Evidence from data on computer use. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 56(3), 511–529. doi:10.2307/3590922.

Gazioglu, S., & Tansel, A. (2006). Job satisfaction in Britain: Individual and job related factors. Applied Economics, 38, 1163–1171. doi:10.1080/00036840500392987.

Gonäs, L., & Karlsson, J. C. (2006). Division of Gender and Work. Chapter 1 in Gonäs, L. and Karlsson, J.C. (eds.): ‘Gender Segregation. Division of Work in Post-Industrial Welfare States’. London.

Gruber, J., & Wise, D. A. (Eds.) (1999). Social Security and Retirement around the World. Chicago: The National Bureau of Economic Research.

Gustman, A., & Steinmeier, T. L. (2000). Retirement in dual-career families: A structural model. Journal of Labor Economics, 18(3), 503–545. doi:10.1086/209968.

Hayward, M. D., & Grady, W. D. (1986). The occupational retention and recruitment of older men: The influence of structural characteristics of work. Social Forces, 64(3), 644–666. doi:10.2307/2578817.

Hayward, M. D., Grady, W. R., Hardy, M. A., & Sommers, D. (1989). Occupational influences on retirement, disability, and death. Demography, 26(3), 393–409. doi:10.2307/2061600.

Holt, Helle, Lars P. Geerdsen, Gunvor Christensen, Caroline Klitgaard and Marie Louise Lind. (2006). ‘Det kønsopdelte arbejdsmarked. En kvantitativ og kvalitativ belysning’. Copenhagen: The Danish National Institute of Social Research 06:02.

Hurd, M. D. (1990). The joint retirement decisions of husbands and wives. In D. A. Wise (Ed.), Issues in the economics of aging (pp. 231–258). Chicago: University of Chicago Press for NBER.

Hurd, M. D., & McGarry, K. (1993). The Relationship Between Job Characteristics and Retirement. Working Paper No. 4558. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Karasek, R. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 285–306. doi:10.2307/2392498.

Karasek, R., & Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy work: Stress, productivity and the reconstruction of working life. New York.

Kooiman, P., Euwals, R., van de Ven, M., & van Vuuren, D. (2004). Price and Income Incentives in Early Retirement: A Preliminary Analysis of a Dutch Pension Reform, paper presented at the NERO 2004 meeting, Paris, OECD.

Larsen, M. (2006). Fastholdelse og rekruttering af ældre. Arbejdspladsers indsats. The National Institute of Social Research 06:09. Copenhagen.

Larsen, M., & Gupta, N. D. (2004). The Impact of Health on Individual Retirement Plans: A Panel Analysis comparing Self-reported versus Diagnostic Measures. Working Paper 04-7. Department of Economics, Aarhus School of Business.

Leonesio, M. V. (1990). Effects of the social security earnings test on the labor-market activity of older Americans: A review of the evidence. Social Security Bulletin, 53(5), 2–21.

Madsen, K. Per. (2005). The danish road to ‘flexicurity’. Where are we? And how did we get there? Chapter 14 in Bredgaard, Thomas and Flemming Larsen (eds.). ‘Employment policy from different angles’. Copenhagen.

McGarry, K. (2004). Health and retirement: Do changes in health affect retirement expectations? The Journal of Human Resources, 39(3), 624–648. doi:10.2307/3558990.

Ministry of Employment (2006). ‘Velfærdsreform’, http://www.bm.dk/sw12500.asp (17.12.2006).

Mitchell, O. S., & Fields, G. S. (1984). The economics of retirement behavior. Journal of Labor Economics, 2(1), 84–105. doi:10.1086/298024.

OECD (2005). Ageing and Employment Policies, Synthesis Report. Paris: OECD.

OECD (2007). OECD Statistics. http://www.oecd.org (02.05.2007).

Quinn, J. (1978). Job characteristics and early retirement. Industrial Relations, 17(3), 315–323. doi:10.1111/j.1468-232X.1978.tb00141.x.

Solem, P. E., & Mykletun, R. (1997). Work Environment and Early Exit from Work, p. 285–92 in Kilbom, Åsa, Peter Westerholm, Lennart Hallsten, and Bengt Furåker. Eds. ‘Work after 45?’ Series Arbete och Hälsa. Solna, Sweden: National Institute for Working life.

Sousa-Poza, A., & Sousa-Poza, A. A. (2000). Taking another look at the gender/job-satisfaction paradox. Kyklos, 53(2), 135–152. doi:10.1111/1467-6435.00114.

Warr, P. (1999). Well-being and the Workplace, in Kahneman, Daniel, Ed Diener and Norbert Schwarz (eds.): ‘Well-being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology’. New York.

Welfare Commission (2004). Fremtidens velfærd kommer ikke af sig selv. Analyserapport. Copenhagen.

Acknowledgement

This work is part of the research of the Graduate School for Integration, Production and Welfare. Financial support from the Danish Social Science Research Council is gratefully acknowledged.

I am grateful for comments by Peder Pedersen, Paul Bingley, Michael Rosholm, Torben Tranæs, Nabanita Datta Gupta and two anonymous referees. Thanks also to the participants at the 4th International Research Conference on Social Security 2003 in Antwerp, the PhD Workshop at the Graduate School for Integration, Production and Welfare 2003 in Odense and the Workplace and Gender Workshop 2005 in Copenhagen. All remaining errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

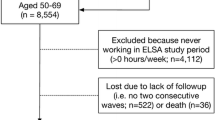

Appendix. Selection of sample

Appendix. Selection of sample

In 1997, a representative sample of individuals born every fifth year from 1920 to 1945, consisting of 5,864 individuals, were interviewed in their homes. The response rate was 70%. In 2002, the same respondents were contacted primarily by phone for a second interview. Seventy-nine percent of the first wave respondents participated in the second wave. Thus, 4,634 individuals form part of both waves.

To minimize sample selection due to retirement, I limit my sample to individuals born in 1940 and 1945, i.e. people aged about 52 and 57 years in 1997. This number corresponds to 2,658 individuals. I also restrict my sample to wage earners (or those temporarily unemployed) in 1997. Consequently, one source of potential sample selection is omission of already retired individuals and individuals who were self-employed. However, as key information on quality of work life measures and many relevant economic characteristics are unavailable for these individuals, including them in the analysis is not possible. Restricting the sample to be representative for wage earners thus results in a sample of 1,836 individuals, corresponding to 69% of the original sample for the two birth cohorts.

A large part (86%) of the selected sample of 1,836 individuals participated in the second wave in 2002. I extend the sample with observations for 2002 for these individuals who are wage earners (or temporarily unemployed) in the second wave. I also include observations for those who retired between the two waves, as I have full information on all covariates on these individuals.Footnote 10 Planned retirement age is set equal to the actual retirement age (reported in the survey) for this group. Including observations from the second wave leaves a sample of 3,360 person-wave observations.

Finally, since the dependent variable is planned (or actual) retirement age, I am only able to include person-wave observations for individuals who report a given age in the wave in question when asked about planned (or actual) retirement age. Unfortunately, in 20% of the cases, the answer was ‘don’t know’ or ‘as long as possible’. While it is feasible to set ‘as long as possible’ to a maximum of, say, 75 or 85 years as in some previous studies (e.g. Dwyer and Mitchell 1999), I hesitate to do so, as this latter group of individuals turns out to be a very heterogeneous group whose characteristics do not generally resemble those individuals who cite a high retirement age. When I throw out person-wave observations without information about an exact planned (or actual) retirement age, I end up with a sample consisting of 2,704 person-wave observations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Larsen, M. Does Quality of Work Life Affect Men and Women’s Retirement Planning Differently?. Applied Research Quality Life 3, 23–42 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-008-9045-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-008-9045-7