Abstract

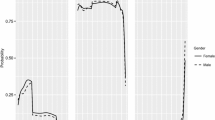

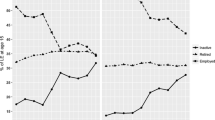

The paper focuses on the Average Effective Age of Retirement (AEAR) indicator allowing policy makers and scientists to evaluate potential gaps between the age of the end of the working life and the pension age in European countries. Used at the European level after the Barcelona European Council of March 2002, this indicator provided by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development raises a number of problems that are reviewed in this article. First, we show that employment rates of older workers dropped continuously in all European countries since 1970. From the mid-1990s and much more in the last 10 years, following European targets designed to increase older workers employment rates, the AEAR increases. Second, we analyse the formula of the AEAR as such. We show that the “employment rate” is the main component of its calculation. Using data from the European Social Surveys a new indicator based on individual data is provided. Last, using Labour Force Surveys, we develop at a macro-level a dynamic reading of labour market taking into account transitions into and outside employment. In addition, we focus particularly—at a micro-level—on individual factors via a multinomial logistic regression performed for Belgium, France and the Netherlands, particularly characterised by high rates of early retirement since the 1970s. We show that uses of exit arrangement vary depending on to gender, the level of education, and the professional and marital status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It should however be noted however that the principle of “job sharing” has been particularly criticised by a majority of economists during the last two decades. For a short state-of-the-art of this topic, see: Wels 2014b.

Obviously, European countries have not all gone through the same path. Some countries have known all these stages while other countries have experienced some selected ones. This is particularly true regarding the share of employment between generations which has been more significantly implemented in continental countries such as France, Belgium or Holland during the 1970’s while other countries such as Sweden or UK didn’t implement that.

The “Average Exit Age from the Labour Force” (AEALF) provided by Eurostat is sometimes used to evaluate the gap between end of employment and retirement. However, this indicator suffers the same methodological problems. As the AEAR, the AEALF can be calculated based on both static method (Latulippe 1996) and dynamic method (Scherer 2002), based on the logic of a cohort approach. Unlike the AEAR using the employment rate, the AEALF used the “activity rate” as a key-indicator. Based on a probability model, this indicator calculates an average age of transition from the active population aged 50–70 (Employed and Unemployed) to the inactive population. While taking into consideration the Activity Rate rather than the Employment Rate makes the indicator less sensitive to economic cycles (affecting mostly unemployment rates), the definition of the “inactivity rate” is still a problem. Indeed, once again, inactivity is considered as retirement while other arrangements and social benefits are also labelled as inactivity. More relevant than the AEAR, the AEALF raises the same issues. Furthermore, available since 2001, the AEALF hasn’t been selected as a significant indicator by European institutions, mainly because of the prevalence of the employment rate (and not the activity rate) in European targets.

“Die Macht der einen Zahl” (“The power of single-number”) is the tittle of a book written by P. Lepenies (2013) dedicated to the history of GDP and its growing importance in economy. As for the AEAR, the GDP is an aggregated number providing clear information about economic trends and, as for the AEAR, this kind of “single-number” should be criticized both historically (how this indicator became a key-indicator) and mathematically (how the indicator is calculated).

The table indicates, by country and gender, the percentage of individuals moving from one status to another between 2010 (or 2011) and 2011 (or 2012). For example, the table shows that, in Austria, 50.2 % of men aged 45–69 moved from “employment” to “employment” between 2010 and 2012.

For a complete definition of the ILO definition of the Employment Rate and criticisms, see Brandolini et al. (2006).

More precisely, we merge in the same multinomial logistic regression model transitions both form 2010 to 2011 and from 2011 to 2012 in order to consolidate the sampling.

Up to now, variables MAINSTAT and STAPRO1Y used for analyzing transition from one year to another are missing in the LFS database.

References

Abbott, A. (1995). Sequence analysis: New methods for old ideas. Annual Review of Sociology, 21, 93–113.

Aranki, T., & Macchiarelli, C. (2013). Employment duration and shifts into retirement in the EU, (1517). Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=2215763.

Aubert, P. (2012). Les âges de sortie d’activité. Revue française des affaires sociales, 4(4), 79–83. Retrieved from http://www.cairn.info/revue-francaise-des-affaires-sociales-2012-4-page-79.htm.

Barbier, J.-C. (2008). Qualité et flexibilité de l’emploi en Europe: de nouveaux risques. In Guillemard A-M (Ed.). Où va la protection sociale? (pp.69-85), Paris: PUF, Le lien social.

Blumer, H. (1971). Social problems as collective behavior. Social Problems, 18(3), 298–306.

Brandolini, A., Cipollone, P., & Viviano, E. (2006). Does the ILO definition capture all unemployment? Journal of the European Economic Association, 4(1), 153–179. doi:10.1162/jeea.2006.4.1.153.

Claes, T. (2012). La prépension conventionnelle (1974–2012). Courrier hebdomadaire du CRISP, 2154–2155, 5–94.

Corna, L. M., & Sacker, A. (2013). A lifetime of experience: Modeling the labour market and family histories of older adults in Britain. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 4(1), 33–56.

Daric, J. (1946). Vieillissement démographique et prolongation de la vie active. Population (French Edition), 1(1), 69–78. doi:10.2307/1524393.

Davoine, L. (2005). The Employment rate of ‘seniors’ and employment quality throughout the life cycle: A comparative approach. TLM.NET Working Paper, 2005(17).

De Vroom, B. (2004). Age-arrangements, age-culture and social citizenship: A conceptual framework for an institutional and social analysis. In T. Maltby, B. de Vroom, M. L. Mirabile, & E. Overbye (Eds.), Ageing and the transition to retirement. A comparative analysis of European welfare states (pp. 6–17). Cornwall: Ashgate.

De Vroom, B., & Guillemard, A.-M. (2002). From externalisation to integration of older workers: Institutional changes at the end of the worklife. In G. Andersen & P. H. Jensen (Eds.), Changing labour markets, welfare policies and citizenship (pp. 183–207). Glasgow: Policy Press.

Delsen, L. (1990). Part-time early retirement in Europe. The Geneva on Risk and Insurance, 15(55), 139–157.

Desmarez, P. (2001). Subordination et indépendance. Note pour une rélfexion sur les relations entre travail indépendant et travail salarié. In M. Alaluf, P. Rolle, & P. Schoetter (Eds.), Division du travail et du social (pp. 281–285). Toulouse: Octares.

Desmet, R., & Pestieau, P. (2003). Sécurité sociale et départ à la retraite. Revue française d’économie, 18(1), 3–21. Retrieved from http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/rfeco_0769-0479_2003_num_18_1_1477.

Evandrou, M., & Glaser, K. (2004). Family, work and quality of life: Changing economic and social roles through the lifecourse. Ageing and Society, 24(5), 771–791. doi:10.1017/S0144686X04002545.

Freyssinet, J. (2004). Taux de chômage ou taux d’emploi, retour sur les objectifs européens. Travail, genre et sociétés, 11(1), 109–120.

Ghesquière, F. (2014). Précarité du contrat de travail et risque de perte d’emploi en Europe. Sociologie, 5(3), 271–290.

Ghesquière, F., & Wels, J. (2014). Revenus du travail et emploi atypique, comparaison entre les analyses sociétales et individuelles. Revue de l’IRES, 81(2), 33–58.

Guillemard, A. -M. (1993). Travailleurs vieillissants et marché du travail en Europe. Travail et emploi, 57, 60–79. Retrieved from http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=3848278.

Guillemard, A.-M. (2002). L’Europe continentale face à la retraite anticipée: Barrières institutionnelles et innovations en matière de réforme. Revue française de sociologie, 43(2), 333–368.

Guillemard, A.-M. (2010). Les défis du vieillissement. Age emploi, retraite. Perspetives internationales. Paris: Artmand Colin.

Holzmann, R. (2012). Global pension systems and their reform. Social protection & labor discussion paper, 1213.

Jacobs, K., Kohli, M., & Rein, M. (1991). The evolution of early exit: A comparative analysis of labour force participation patterns. In M. Kohli, M. Rein, A.-M. Guillemard, & H. Van Gunsteren (Eds.), Time for retirement. Comparative studies of early exit from the labour force (pp. 36–66). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jolivet, A. (2006). Usages nationaux des sorties anticipées liées à la santé: les exemples suédois et néerlandais. Retraite et société, 49(3), 99–119. Retrieved from http://www.cairn.info/revue-retraite-et-societe-2006-3-page-99.htm.

Jousten, A., & Lefèbvre, M. (2010). The effects of early retirement on youth unemployment: The case of Belgium. In J. Gruber & D. A. Wise (Eds.), Social security programs and retirement around the world: The relationship to youth employment (pp. 47–76). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8251.pdf.

Latulippe, D. (1996). Effective retirement age and duration of retirement in the industrial countries between 1950 and 1990. International Labor Office. doi:10.1016/S0022-3913(12)00047-9.

Lepenies, P. (2013). Die Macht der einen Zahl: Eine politische Geschichte des Bruttoinlandsprodukts. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Monnier, A. (1979). Les limites de la vie active et la retraite: I. L’âge au départ en retraite: âge effectif, âge probable, âge souhaité. Population (French Edition), 34(4/5), 801–823. doi:10.2307/1533003.

Mouhanna, C. (2011). Entretien avec Alain Desrosières. Sociologies pratiques, 22(1), 15–18.

OECD. (2006). Vivre et travailler plus longtemps. Paris: Editions OECD. Retrieved from http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/employment/vivre-et-travailler-plus-longtemps_9789264035898-fr.

OECD. (2011). Panorama des pensions 2011: les systèmes de retraites dans les pays de l’OECD et du G20 (p. 372).

Paugam, S. (1993). La société française et ses pauvres. Paris: PUF.

Robinson, W. S. (1950). Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. American Journal of Sociology, 15, 351–357.

Salais, R. (2004). La politique des indicateurs. Du taux de chômage au taux d’emploi dans la stratégie européenne pour l’emploi (SEE). In B. Zimmermann (Ed.), Les sciences sociales à l’épreuve de l’action. Le savant, le politique et l’Europe (pp. 1–28). Paris: Maison des Sciences de l’Homme.

Scherer, P. (2002). Age of withdrawal from the labour force in OECD countries. Paris. doi:10.1787/327074367476.

Schmid, G. (1995). Le plein emploi est-il encore possible? Travail et emploi, 65, 5–18. Retrieved from http://www.travail-emploi-sante.gouv.fr/publications/Revue_Travail-et-Emploi/pdf/65_69.pdf.

Spasova, S. (2013). Les réformes des retraites dans les pays d’Europe centrale et orientale : entre influences internationales et déterminants nationaux. La revue de l’IRES, 77(2), 129–163.

Wels, J. (2014a). La politique des fins de carrière. Vers un modèle européen convergent ? Sociologie, 5(3), 233–253.

Wels, J. (2014b). Le partage d’emploi entre générations. Analyse des effets régulateurs et redistributifs de la réduction du temps de travail en fin de carrière sur l’emploi des jeunes. Recherches Sociologiques et Anthropologiques, 45(2), 157–174.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wels, J. The Statistical Analysis of End of Working Life: Methodological and Sociological Issues Raised by the Average Effective Age of Retirement. Soc Indic Res 129, 291–315 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1103-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1103-6