Abstract

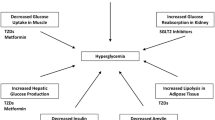

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are agonists of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) nuclear transcription factor. Two members of this drug class, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, are commonly used in the management of type II diabetes mellitus, and play emerging roles in the treatment of other clinical conditions characterized by insulin resistance. Over the past decade, a consistent body of in vitro and animal studies has demonstrated that PPARγ signaling regulates the fate of pluripotent mesenchymal cells, favoring adipogenesis over osteoblastogenesis. Treatment of rodents with TZDs decreases bone formation and bone mass. Until recently, there were no bone-related data available from studies of TZDs in humans. In the past year, however, several clinical studies have reported adverse skeletal actions of TZDs in humans. Collectively, these investigations have demonstrated that the TZDs currently in clinical use decrease bone formation and accelerate bone loss in healthy and insulin-resistant individuals, and increase the risk of fractures in the appendicular skeleton in women with type II diabetes mellitus. These observations should prompt clinicians to evaluate fracture risk in patients for whom TZD therapy is being considered, and initiate skeletal protection in at-risk individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Henney JE (2000) From the food and drug administration. JAMA 283:2228

Yki-Jarvinen H (2004) Thiazolidinediones. N Engl J Med 351:1106–1118

Yki-Jarvinen H (2005) The PROactive study: some answers, many questions. Lancet 366:1241–1242

Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA et al (2006) Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. N Engl J Med 355:2427–2443

Stout DL, Fugate SE (2005) Thiazolidinediones for treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome. Pharmacotherapy 25:244–252

Dream Trial Investigators (2006) Effect of rosiglitazone on the frequency of diabetes in patients with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 368:1096–1105

Nissen SE, Wolski K (2007) Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 356:2457–2471

Psaty BM, Furberg CD (2007) Rosiglitazone and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 356:2522–2524

[no authors listed] (2007) Rosiglitazone: seeking a balanced perspective. Lancet 369:1834

Krall RL (2007) Cardiovascular safety of rosiglitazone. Lancet 369:1995–1996

Home PD, Pocock SJ, Beck-Nielsen H et al (2007) Rosiglitazone evaluated for cardiovascular outcomes—an interim analysis. N Engl J Med 357:28–38

Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJA et al (2005) Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 366:1279–1289

Vestergaard P (2007) Discrepancies in bone mineral density and fracture risk in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes—a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 18:427–444

Strotmeyer ES, Cauley JA, Schwartz AV et al (2005) Nontraumatic fracture risk with diabetes mellitus and impaired fasting glucose in older white and black adults: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition study. Arch Intern Med 165:1612–1617

Nicodemus KK, Folsom AR (2001) Type 1 and type 2 diabetes and incident hip fractures in postmenopausal women. Diabetes Care 24:1192–1197

Schwartz AV, Sellmeyer DE, Ensrud KE et al (2001) Older women with diabetes have an increased risk of fracture: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:32–38

Bonds DE, Larson JC, Schwartz AV et al (2006) Risk of fracture in women with type 2 diabetes: the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:3404–3410

Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L (2005) Relative fracture risk in patients with diabetes mellitus, and the impact of insulin and oral antidiabetic medication on relative fracture risk. Diabetologia 48:1292–1299

Ivers RQ, Cumming RG, Mitchell P et al (2001) Diabetes and risk of fracture: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Diabetes Care 24:1198–1203

Ahmed LA, Joakimsen RM, Berntsen GK et al (2006) Diabetes mellitus and the risk of non-vertebral fractures: the Tromso study. Osteoporos Int 17:495–500

Miao J, Brismar K, Nyren O et al (2005) Elevated hip fracture risk in type 1 diabetic patients: a population-based cohort study in Sweden. Diabetes Care 28:2850–2855

Whiteside GT, Boulet JM, Sellers R et al (2006) Neuropathy-induced osteopenia in rats is not due to a reduction in weight born on the affected limb. Bone 38:387–393

Cundy TF, Edmonds ME, Watkins PJ (1985) Osteopenia and metatarsal fractures in diabetic neuropathy. Diabet Med 2:461–464

Zhou Z, Immel D, Xi C-X et al (2006) Regulation of osteoclast function and bone mass by RAGE. J Exp Med 203:1067–1080

Katayama Y, Akatsu T, Yamamoto M et al (1996) Role of nonenzymatic glycosylation of type I collagen in diabetic osteopenia. J Bone Miner Res 11:931–937

Miyata T, Notoya K, Yoshida K et al (1997) Advanced glycation end products enhance osteoclast-induced bone resorption in cultured mouse unfractionated bone cells and in rats implanted subcutaneously with devitalized bone particles. J Am Soc Nephrol 8:260–270

Gimble JM, Robinson CE, Wu X et al (1996) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation by thiazolidinediones induces adipogenesis in bone marrow stromal cells. Mol Pharmacol 50:1087–1094

Johnson TE, Vogel R, Rutledge SJ et al (1999) Thiazolidinedione effects on glucocorticoid receptor-mediated gene transcription and differentiation in osteoblastic cells. Endocrinology 140:3245–3254

Jeon MJ, Kim JA, Kwon SH et al (2003) Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma inhibits the Runx2-mediated transcription of osteocalcin in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem 278:23270–23277

Jackson SM, Demer LL (2000) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor activators modulate the osteoblastic maturation of MC3T3-E1 preosteoblasts. FEBS Lett 471:119–124

Diascro DD, Vogel RL, Johnson TE et al (1998) High fatty acid content in rabbit serum is responsible for the differentiation of osteoblasts into adipocyte-like cells. J Bone Miner Res 13:96–106

Nuttall ME, Patton AJ, Olivera DL et al (1998) Human trabecular bone cells are able to express both osteoblastic and adipocytic phenotype: implications for osteopenic disorders. J Bone Miner Res 13:371–382

Mbalaviele G, Abu-Amer Y, Meng A et al (2000) Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma pathway inhibits osteoclast differentiation. J Biol Chem 275:14388–14393

Chan BY, Gartland A, Wilson PJM et al (2007) PPAR agonists modulate human osteoclast formation and activity in vitro. Bone 40:149–159

Lecka-Czernik B, Gubrij I, Moerman EJ et al (1999) Inhibition of Osf2/Cbfa1 expression and terminal osteoblast differentiation by PPARgamma2. J Cell Biochem 74:357–371

Khan E, Abu-Amer Y (2003) Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma inhibits differentiation of preosteoblasts. J Lab Clin Med 142:29–34

Kawaguchi H, Akune T, Yamaguchi M et al (2005) Distinct effects of PPARgamma insufficiency on bone marrow cells, osteoblasts, and osteoclastic cells. J Bone Miner Metab 23:275–279

Lecka-Czernik B, Moerman EJ, Grant DF et al (2002) Divergent effects of selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma 2 ligands on adipocyte versus osteoblast differentiation. Endocrinology 143:2376–2384

Kim SH, Yoo CI, Kim HT et al (2006) Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARgamma) induces cell death through MAPK-dependent mechanism in osteoblastic cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 215:198–207

Okazaki R, Toriumi M, Fukumoto S et al (1999) Thiazolidinediones inhibit osteoclast-like cell formation and bone resorption in vitro. Endocrinology 140:5060–5065

Reid IR, Cornish J, Baldock PA (2006) Nutrition-related peptides and bone homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res 21:495–500

Fain JN, Cowan GS Jr, Buffington C et al (2000) Regulation of leptin release by troglitazone in human adipose tissue. Metabolism 49:1485–1490

Williams LB, Fawcett RL, Waechter AS et al (2000) Leptin production in adipocytes from morbidly obese subjects: stimulation by dexamethasone, inhibition with troglitazone, and influence of gender. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:2678–2684

Cornish J, Callon KE, Bava U et al (2002) Leptin directly regulates bone cell function in vitro and reduces bone fragility in vivo. J Endocrinol 175:405–415

Ducy P, Amling M, Takeda S et al (2000) Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay: a central control of bone mass. Cell 100:197–207

Maeda N, Takahashi M, Funahashi T et al (2001) PPARgamma ligands increase expression and plasma concentrations of adiponectin, an adipose-derived protein. Diabetes 50:2094

Oshima K, Nampei A, Matsuda M et al (2005) Adiponectin increases bone mass by suppressing osteoclast and activating osteoblast. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 331:520–526

Williams GA, Callon KE, Watson M et al (2006) Adiponectin knock-out mice have increased trabecular number and bone volume at 14 weeks of age. Australia New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society, Port Douglas, QA, O28

Cornish J, Callon KE, Reid IR (1996) Insulin increases histomorphometric indices of bone formation in vivo. Calcif Tissue Int 59:492–495

Cornish J, Callon KE, King AR et al (1998) Systemic administration of amylin increases bone mass, linear growth, and adiposity in adult male mice. Am J Physiol 38:E694–E699

Cornish J, Callon KE, Bava U et al (2007) Preptin, another peptide product of the pancreatic beta-cell, is osteogenic in vitro and in vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292:E117–E122

Lecka-Czernik B, Ackert-Bicknell C, Adamo ML et al (2007) Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) by rosiglitazone suppresses components of the insulin-like growth factor regulatory system in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology 148:903–911

Jennermann C, Triantafillou J, Cowan D et al (1995) Effects of thiazolidinediones on bone turnover in the rat. J Bone Miner Res 10 [Suppl 1]:S241

Rzonca SO, Suva LJ, Gaddy D et al (2004) Bone is a target for the antidiabetic compound rosiglitazone. Endocrinology 145:401–406

Ali AA, Weinstein RS, Stewart SA et al (2005) Rosiglitazone causes bone loss in mice by suppressing osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Endocrinology 146:1226–1235

Soroceanu MA, Miao D, Bai X-Y et al (2004) Rosiglitazone impacts negatively on bone by promoting osteoblast/osteocyte apoptosis. J Endocrinol 183:203–216

Li M, Pan LC, Simmons HA et al (2006) Surface-specific effects of a PPAR-gamma agonist, darglitazone, on bone in mice. Bone 39:796–806

Lazarenko OP, Rzonca SO, Suva LJ et al (2006) Netoglitazone is a PPAR-gamma ligand with selective effects on bone and fat. Bone 38:74–84

Tornvig L, Mosekilde LI, Justesen J et al (2001) Troglitazone treatment increases bone marrow adipose tissue volume but does not affect trabecular bone volume in mice. Calcif Tissue Int 69:46–50

Sottile V, Seuwen K, Kneissel M (2004) Enhanced marrow adipogenesis and bone resorption in estrogen-deprived rats treated with the PPARgamma agonist BRL49653 (rosiglitazone). Calcif Tissue Int 75:329–337

Lazarenko OP, Rzonca SO, Hogue WR et al (2007) Rosiglitazone induces decreases in bone mass and strength that are reminiscent of aged bone. Endocrinology 148:2669–2680

Akune T, Ohba S, Kamekura S et al (2004) PPAR-gamma insufficiency enhances osteogenesis through osteoblast formation from bone marrow progenitors. J Clin Invest 113:846–855

Klein RF, Allard J, Avnur Z et al (2004) Regulation of bone mass in mice by the lipoxygenase gene Alox15. Science 303:229–232

Okazaki R, Miura M, Toriumi M et al (1999) Short-term treatment with troglitazone decreases bone turnover in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr J 46:795–801

Watanabe S, Takeuchi Y, Fukumoto S et al (2003) Decrease in serum leptin by troglitazone is associated with preventing bone loss in type 2 diabetic patients. J Bone Miner Metab 21:166–171

Schwartz AV, Sellmeyer DE, Vittinghoff E et al (2006) Thiazolidinedione use and bone loss in older diabetic adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:3349–3354

Yaturu S, Bryant B, Jain SK (2007) Thiazolidinediones treatment decreases bone mineral density in type 2 diabetic men. Diabetes Care 30:1574–1576

Grey A, Bolland M, Gamble G et al (2007) The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist rosiglitazone decreases bone formation and bone mineral density in healthy postmenopausal women: a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:1305–1310

Berberoglu Z, Gursoy A, Bayraktar N et al (2007) Rosiglitazone decreases serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase activity in postmenopausal diabetic women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:3523–3530

Ton FN, Gunawardene SC, Lee H et al (2005) Effects of low-dose prednisone on bone metabolism. J Bone Miner Res 20:464–470

Sanders KM, Seeman E, Ugoni AM et al (1999) Age- and gender-specific rate of fractures in Australia: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int 10:240–247

Garraway WM, Stauffer RN, Kurland LT et al (1979) Limb fractures in a defined population. I. Frequency and distribution. Mayo Clin Proc 54:701–707

US Food and Drug Administration. Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/medwatch/safety/2007/Avandia_GSK_Ltr.pdf on 3 March 2007

US Food and Drug Administration. Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/medwatch/safety/2007/Actosmar0807.pdf on 13 March 2007

Saag KG, Emkey R, Schnitzer TJ et al (1998) Alendronate for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis Intervention Study Group. N Engl J Med 339:292–299

Adachi JD, Saag KG, Delmas PD et al (2001) Two-year effects of alendronate on bone mineral density and vertebral fracture in patients receiving glucocorticoids: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled extension trial. Arthritis Rheum 44:202–211

Grey AB, Cundy TF, Reid IR (1994) Continuous combined oestrogen/progestin therapy is well tolerated and increases bone density at the hip and spine in post-menopausal osteoporosis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 40:671–677

National Osteoporosis Foundation (2003) Physician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. In. National Osteoporosis Foundation, Washington, DC

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (2003) Medical guidelines for clinical practice for the prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Pract 9:544–564

Acknowledgements

Funding support is provided by the Health Research Council of New Zealand. The author is grateful to Ian Reid MD for reviewing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grey, A. Skeletal consequences of thiazolidinedione therapy. Osteoporos Int 19, 129–137 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0477-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0477-y