Abstract

Purpose

Pain, dyspnea, and thirst are three of the most prevalent, intense, and distressing symptoms of intensive care unit (ICU) patients. In this report, the interdisciplinary Advisory Board of the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU (IPAL-ICU) Project brings together expertise in both critical care and palliative care along with current information to address challenges in assessment and management.

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive review of literature focusing on intensive care and palliative care research related to palliation of pain, dyspnea, and thirst.

Results

Evidence-based methods to assess pain are the enlarged 0–10 Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) for ICU patients able to self-report and the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool or Behavior Pain Scale for patients who cannot report symptoms verbally or non-verbally. The Respiratory Distress Observation Scale is the only known behavioral scale for assessment of dyspnea, and thirst is evaluated by patient self-report using an 0–10 NRS. Opioids remain the mainstay for pain management, and all available intravenous opioids, when titrated to similar pain intensity end points, are equally effective. Dyspnea is treated (with or without invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation) by optimizing the underlying etiological condition, patient positioning and, sometimes, supplemental oxygen. Several oral interventions are recommended to alleviate thirst. Systematized improvement efforts addressing symptom management and assessment can be implemented in ICUs.

Conclusions

Relief of symptom distress is a key component of critical care for all ICU patients, regardless of condition or prognosis. Evidence-based approaches for assessment and treatment together with well-designed work systems can help ensure comfort and related favorable outcomes for the critically ill.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Critical illness and its management in the intensive care unit (ICU) present special challenges for control of pain and other symptoms that cause patient distress. Many patients cannot provide self-reports, the gold standard of symptom information, in real time. Interventions used to diagnose and treat critical illness are themselves common sources of symptom distress, as are routine and noninvasive aspects of patient care such as turning. Treatments to relieve symptoms must take account of the complex pharmacologic and physiologic issues that accompany multiple organ failures. At the same time, relief of symptom distress is a foundational aspect of palliative care, which is an integral component of comprehensive critical care for all ICU patients, from the time of admission, regardless of prognosis [1, 2]. Evidence-based strategies for symptom assessment and management can not only promote patient comfort in the ICU but help modulate the stress response, with potential physiologic benefits [3–5]. When knowledge and skill are applied in a systematic effort, symptom relief can be fully consistent with restorative treatment of critical illness [6].

Expert guidelines are available to assist in the management of pain [7] and dyspnea [8, 9], but additional empirical evidence to support clinical care is needed, and wide variation in practice is common. Meanwhile, the high prevalence, frequency, and intensity of other distressing physical symptoms, such as thirst, and psychological symptoms, have come into clearer view recently, but without development and rigorous testing of palliative interventions. The Improving Palliative Care in the ICU (IPAL-ICU) Project, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health and the Center to Advance Palliative Care, shares technical assistance, evidence, and tools to integrate palliative care and intensive care successfully from the onset of critical illness for all ICU patients, including those pursuing intensive therapies to prolong life and restore baseline health. In this review, the interdisciplinary IPAL-ICU Advisory Board brings together the combined expertise of its members in palliative care and intensive care to address challenges in assessment and management of pain, dyspnea, and thirst during critical illness. We focus on the following questions: (1) What are key elements necessary to assess these three common symptoms in the ICU? (2) What are optimal strategies for managing these symptoms during critical illness? (3) How can symptom care be systematized for improvement?

What are the most prevalent and distressing symptoms experienced by critically ill patients?

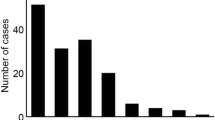

Over a period spanning two decades, studies conducted in various ICU settings confirm that pain, dyspnea, and thirst are among the most prevalent and distressing physical symptoms experienced by critically ill patients who can provide a symptom self-report. In a survey from the early 1990s, 70 % of patients recalled pain (rated as moderate or severe by 63 %) during treatment in medical and surgical ICUs [10]. Findings of a more recent study [11] were strikingly similar: 77 % of patients transferred from cardiac surgery ICUs recalled pain, and 64 % of them rated the pain as moderate or severe. In a study of critically ill cancer patients receiving ICU care, 56 % of those who could self-report symptoms experienced moderate or severe pain, while 34 and 71 % reported dyspnea and unsatisfied thirst, respectively, at these levels [12]. In another recent study, more than 400 interviews with 171 critically ill patients at high risk of dying revealed pain in 40 %, dyspnea in 44 %, and thirst in 71 % of these assessments [13]. A study focusing on patients receiving mechanical ventilation showed that almost half of patients experienced dyspnea, which was significantly associated with anxiety [14]. The contribution of diagnostic and treatment-related procedures to pain and other suffering in the ICU has been demonstrated in major studies in the USA and elsewhere. Evaluating more than 6,000 patients in 167 ICUs, the Thunder Project II® examined the painfulness of turning, tracheal suctioning, non-burn wound care, wound drain removal, central line insertion, and femoral sheath removal [15]. The most painful procedure for adults was turning. Post-cardiac and abdominal surgery ICU patients reported moderate to severe pain associated with endotracheal (ET) suctioning and/or chest tube removal [16]. Moderate to severe pain has been reported by over 30 % of cancer patients who underwent the following ICU procedures: ET suctioning, turning, arterial blood gas puncture, arterial catheter insertion, central catheter insertion, or peripheral intravenous (IV) insertion [12]. The symptom experience of cognitively impaired patients is less well understood [17].

What are key elements necessary to assess symptoms in the ICU?

The cornerstone of effective symptom control is systematic symptom assessment. Ideally, symptoms are reported and rated by patients themselves, using a tool that is sufficiently simple and brief while providing adequate information for clinical use. Below is a summary of approaches for ICU patients who can report their symptoms, either verbally or non-verbally, and for non-communicative patients.

Assessment approaches for communicative patients

Table 1 presents symptom assessment tools for use with ICU patients who can communicate verbally (by stating their answers) or non-verbally (by pointing to numbers or words that rate or describe their pain or by pointing to a body outline diagram to localize their pain). Owing to its simplicity, a 0–10 Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), with anchor words at each end that identify extremes of severity, is recommended for assessing dyspnea in patients with advanced illness [18]. The NRS has also been used frequently to measure the intensity and distress of pain [15, 19, 20] and thirst/dry mouth [21]; patients can say or point to a number that approximates symptom severity. A 0–10 visually enlarged, horizontal NRS was found to be the most valid and feasible of five pain intensity rating scales tested in over 100 self-reporting ICU patients [22]. A vertical visual analog scale (VAS) was preferred by patients over a horizontal VAS for reporting dyspnea [23]. Like an NRS, a VAS allows for measurement of symptom severity but the VAS is difficult for many patients in the ICU to understand and use.

The Condensed Form of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale [24] and the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale [25] are tools that allow for verbal or non-verbal patient reports by which a diverse group of physical symptoms including pain and dyspnea as well as psychological symptoms can be measured. Recently, a 10-item multi-symptom scale was validated in a large group of self-reporting ICU patients [13]. Clinicians can provide patients opportunities to report symptoms by having them point to one of these short symptom word lists or helping them to localize their pain by offering body outline diagrams and asking patients to point to the place(s) where they are feeling pain [19]. Speech language pathologists can help augment the patient’s ability to communicate and to assist communication through alternative approaches [26]. Such strategies include alphabet and number boards, electronic speech-generating devices, or a touch screen requiring minimal physical pressure to activate message buttons.

Assessment approaches for non-communicative patients

Three approaches have been used to help understand the experience of patients who cannot report their symptoms verbally or non-verbally: (1) behavioral assessment; (2) proxy assessment; and (3) presumption of symptom distress in situations in which communicative patients typically report such distress.

Behavioral symptom assessment

Important advances have been made in development of pain assessment tools based on patient behaviors. The Behavior Pain Scale (BPS) [27] and the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) [28] have good psychometric properties and are recommended for use with adult ICU patients excluding those with brain injuries [7]. All such tools must be used cautiously, since the findings are an indirect representation of a patient’s perceptual experience. Investigators validated specific procedure-related pain behaviors in a large study of procedural pain, with the most frequent being grimacing, rigidity, wincing, shutting of eyes, verbalization, moaning, and clenching of fists [29].

The Respiratory Distress Observation Scale (RDOS) is the only known behavioral scale for assessment of dyspnea. RDOS includes eight observer-rated parameters: heart rate, respiratory rate, accessory muscle use, paradoxical breathing pattern, restlessness, grunting at end-expiration, nasal flaring, and a fearful facial display. Each parameter is scored on an ordinal scale from 0 to 2 points and the points are summed. Behavior variables that comprise the RDOS were identified from videotaping mechanically ventilated patients undergoing a failed ventilator weaning trial and experiencing dyspnea [30]. Construct, convergent, and discriminant validity have been demonstrated for this tool, as have internal consistency and inter-rater reliability [31, 32].

Proxy symptom assessment

The use of symptom reports from surrogates, such as family members, or bedside clinicians, remains controversial. In some studies, patients rank their symptoms higher than proxy reporters [33, 34], while in other reports the opposite is true [35, 36]. Recently, the agreement between ICU patients and their family members on the distress of patient pain, dyspnea, restlessness, fear, and thirst was demonstrated to be moderately strong [37]. Overall, data suggest that proxy reporters can help identify symptoms that might be distressing for the patient. In addition, although evidence remains limited, proxy data may be useful for trending symptom distress over time.

Assume symptom presence under certain circumstances

When patients are unable to self-report, and unable to demonstrate symptom-related behaviors (such as when chemically paralyzed), clinicians can use their experience and judgment to identify possible sources of symptom distress. The assumption that the patient is experiencing distress from pain, thirst, or dyspnea given the surrounding circumstances may lead clinicians to further attempts to determine the presence of the symptom and address it appropriately. An analgesic trial, starting with a low dose fast-acting opioid (e.g., fentanyl), followed by observation of the patient for pain-related behaviors, may help to verify the presence of pain [38, 39]. If behaviors indicating pain persist and no other cause for the behaviors has been identified, the initial dose can be increased. Alternatively, if pain-related behaviors seem to decrease in response to the analgesic, further interventions, such as scheduled analgesic dosing, can be planned. The same approach can be applied to observed respiratory distress using opioids.

What are current strategies for managing symptoms during critical illness?

Pain

Treatments to relieve symptoms must take into account the complex pharmacologic and physiologic issues that accompany multiple organ failures. Concerns about secondary effects of certain treatments, including hypotension, sedation, respiratory depression, delirium, and other alterations of consciousness, further complicate patient management.

Opioids remain the primary medications to manage pain in ICU patients [40]. Recent guidelines from the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) [7] recommend intravenously administered opioids as the drug class of choice to treat non-neuropathic pain in critically ill patients. These guidelines note that all available intravenously administered opioids, when titrated to similar pain intensity end points, are equally effective, and the optimal choice of opioid and the dosing regimen used for an individual patient depend on many factors including age, underlying comorbidities/end-organ function, and the chosen opioid’s pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. Although some opioid side effects (e.g., sedation) tend to abate with continued treatment, constipation is the most common persistent side effect. Thus, except in the face of bowel obstruction, diarrhea, or another contraindication, a bowel regimen with a stimulant (e.g., senna) or osmotic (e.g., lactulose) laxative must be prescribed when sustained opioid dosing is initiated. Tracking bowel function is a basic component of ICU monitoring. Table 2 summarizes key elements of using opioids for critically ill patients.

Non-opioid analgesics can be used in the ICU including orally or intravenously administered acetaminophen [41]; intravenously administered ketamine [42]; intravenously administered nefopam [43, 44] (thought to inhibit reuptake of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin; used primarily in Europe); and orally, intravenously, and rectally administered cyclooxygenase inhibitors [45], although the last of these are limited by their side effect profile. Use of these medications in conjunction with opioids may decrease the overall quantity of opioids administered and the incidence and severity of opioid-related side effects [7]. All non-opioid analgesics should be used with caution because of drug-specific toxicities that may affect end-organ function [46]. For patients with neuropathic pain, gabapentin and carbamazepine can be considered [47, 48]. Both are categorized as antiepileptic and antihyperalgesic drugs, and both have been tested in ICU patients. Newer drugs for neuropathic pain such as pregabalin, lamictal, trileptal, duloxetine, and venlafaxine require further testing during critical illness. Intravenously administered acetaminophen is now approved for use in the USA. Its safety and effectiveness as an adjunct to opioids have been demonstrated in ICU patients after major general [41] and cardiac surgery, but it may not be necessary unless enteral administration is contraindicated [49]. Ketamine, an anesthetic and analgesic agent, has been used in ICU patients to help prevent or reduce opioid tolerance and to provide pain relief, especially when pain is refractory to opioids and other agents [50, 51]. Ketamine is an N-methyl-d-aspartate/glutamate receptor (NMDA) antagonist that interferes with the normal excitatory effects of glutamate and aspartate and also interacts with opioid receptors [51]. Sub-anesthetic doses of ketamine can be administered with opioids to help reduce the overall opioid dose [51]. With or without coadministration of opioids, patients receiving ketamine may experience psychotomimetic side effects (dysphoria, nightmares, hallucinations), especially at higher ketamine doses. There is limited research on the efficacy of regional anesthetics in ICU patients, although thoracic epidural anaesthesia/analgesia is recommended by the American College of Critical Care Medicine for consideration for postoperative pain in patients undergoing abdominal aortic surgery [7].

Treating pain in the presence of physiologic instability is an ongoing concern of ICU clinicians. Fears of hypotension, respiratory depression, sedation, and addiction are often exaggerated but may lead to physician reluctance to prescribe appropriate analgesia and to administration of suboptimal doses by nurses [52–55]. Clinicians should not allow pain or other distressing symptoms to persist as a way to help maintain blood pressure and/or stimulate respiratory effort. Clinicians should use all ICU resources (interdisciplinary team along with patient and family input) and seek consultative advice if necessary to find an appropriate combination of symptom relief and physiologic stability in the context of the patient’s goals of care [5]. Preventing pain could actually be associated with better control of the acute stress response in patients which could, in turn, increase physiological stability.

Non-pharmacologic interventions for pain management, such as massage, music therapy, and relaxation techniques, cost little and are safe and easy to provide. However, the effectiveness of non-pharmacologic interventions for pain in ICU patients is not yet clearly established by empirical evidence [46, 56].

More than a decade ago, guidelines were published for management of acute and procedure-related pain [57]. Simple pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions exist to decrease such pain. Still, few patients undergoing procedures receive a specific intervention for procedural pain [40]. ICU clinicians should be prepared to premedicate even for procedures that can be completed quickly, such as chest tube or sheath removal, or for routine procedures (such as turning or bathing) that are painful for many patients. Opioids and/or non-opioids with rapid onset and offset, augmented by relaxation, visualization, or other techniques, can be used to prevent or decrease procedural pain.

Dyspnea

Dyspnea is treated by optimizing the underlying etiological condition, such as with inotropes and diuretics for heart failure, along with drug and non-drug treatments. Mechanical ventilation, invasive or noninvasive, can reduce dyspnea from respiratory failure, but may not be appropriate for some patients in light of risks and burdens to the patient, and some mechanically ventilated patients experience dyspnea [14]. The use of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) for symptom palliation in patients forgoing invasive mechanical ventilation was addressed by a task force of the SCCM [58]. Although NIV can be an effective treatment for acute respiratory failure associated with exacerbation of obstructive lung disease, cardiogenic pulmonary edema, neuromuscular disease, and certain other conditions, effectiveness for relief of dyspnea is less well established. NIV was more effective than oxygen in reducing dyspnea and the need for morphine in a study of patients with solid tumors and respiratory failure, particularly those with hypercarbia; however, NIV was discontinued in 7 % of the study group owing to patient intolerance [59]. In a descriptive study of other outcomes of NIV in patients with do-not-intubate directives, dyspnea was not measured; 10 % of these patients requested discontinuation of NIV and 76 % experienced disruption of sleep quality, as evaluated by nurses [60, 61]. As stated by the SCCM’s task force, the appropriate end point for use of NIV with a critically ill patient whose treatment is focused exclusively on comfort is symptom relief, while failure to improve or distress warrant discontinuation of NIV [58]. Some patients will not want to undergo any form of mechanical ventilation and the treatment of dyspnea will rely on drug and non-drug treatments (see Table 3).

Positioning can be an important non-pharmacologic treatment. For example, dyspnea in COPD can be reduced by upright positioning with arms elevated on pillows or a bedside table [62, 63]. In unilateral lung disease a side-lying position may be optimal, with the “good” lung up or down to increase perfusion and/or ventilation. Using the patient as his/her own control and measuring dyspnea or respiratory distress in various positions will help to identify the best position. Patient activity, whether active or passive, increases oxygen consumption that may lead to dyspnea. Since nurses coordinate most patient care in the ICU, their input is essential in determining timing of activity to minimize or prevent dyspnea.

Oxygen is considered standard therapy for dyspnea in patients with hypoxemia [64, 65], but robust data are lacking and no predictable relationship has been found between the degree of hypoxemia and the symptomatic response to supplemental oxygen [66, 67]. No benefit from oxygen compared to medical air was found in a study of patients with advanced lung disease who were not hypoxemic [68]. Patients who were near death and at risk for dyspnea remained comfortable without oxygen [69]. A fan directed at the patient’s face may provide relief [70], although use in the ICU may be limited by bioengineering restrictions.

Opioids are the mainstay of pharmacological management of dyspnea that is refractory to disease-modifying and/or non-pharmacologic symptom treatment, and their effectiveness has been demonstrated in numerous clinical trials [54, 55]. The doses of opioids for acute dyspnea exacerbations are less well known than those used to treat acute pain. “Low and slow” intravenous titration of an immediate-release opioid, repeated every 15 min, should be provided until the patient reports or displays relief. Around the clock dosing may be best if the patient has dyspnea continuously or at rest, but with pro re nata (prn) dosing for episodic dyspnea [71]. Benzodiazepines have not generally been effective as a primary treatment for dyspnea [72]. The addition of an adjunctive benzodiazepine to the opioid regimen has been successful in patients with advanced COPD [73, 74]. As with opioids, these agents should be titrated to effect.

Thirst and xerostomia

Several methods of alleviating thirst and xerostomia (dry mouth) have been identified. Topical products that contain olive oil, betaine, and xylitol, artificial saliva, and salivary flow stimulants have been effective [75]. The effectiveness of frozen gauze pads with normal saline, wet gauze, or ice was documented in post-laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients [76]; patients receiving frozen gauze or ice reported significantly less thirst than patients receiving wet gauze pads. These interventions have not been specifically tested in ICU patients. A randomized trial was recently completed in ICU patients to test the effects of sprays of cold sterile water, swabs of cold sterile water, and use of a mouth and lip moisturizer [21]. This “bundle” of thirst interventions significantly decreased thirst intensity and distress in a group of ICU patients when compared to patients who did not receive the intervention. Use of lemon–glycerin swabs is not recommended because they produce an acid pH [77], dry oral tissues [78], cause irreversible enamel softening and erosion [79], and exhaust salivary mechanisms over time, leading to increased xerostomia [80]. For non-intubated patients receiving high flow oxygen therapy, the use of heated humidifiers versus bubble humidifiers significantly lowered mouth and throat dryness [81]. Table 4 provides a summary of key steps to assess and manage thirst in the ICU patient.

Incorporating family members in symptom management

Family members may want to participate in providing symptom care as a way of feeling connected to their critically ill loved one. Most family members want to be with the patient [82] and to know about the patient’s condition and treatments [83]; patients value this [1]. Some seek directions as to what they can do at the bedside [83]. In a survey of 20 relatives and 27 ICU nurses [84], a high proportion of both agreed that families can be involved in physical care of the patient including mouth and eye care, bed bathing, turning, and positioning the patient. ICU family members have identified themselves as providing care to their loved ones including massaging, repositioning, distracting, and assisting with activities of daily living [85]. Thus, family members can be queried about their interest in assisting with pain, dyspnea, and thirst-relieving measures. For example, they might assist in evaluating patients’ responses to procedures and activities that can cause pain (such as turning, suctioning, and mobilization) [15] and report their observations to the ICU team. They might help the patient find an optimal position and use a fan that reduces dyspnea. Family members could provide simple mouth care and/or ice chips to relieve thirst if not contraindicated. While not all family members want to provide direct care [86], inclusion of interested families in providing patient care can have positive effects for patients and family members alike. Family members who were invited to provide care were almost twice as likely to perceive more respect, increased collaboration, greater support, and higher overall family-centered care (ORs 1.6–1.9) from ICU staff than control group families [87].

Involvement of palliative care specialists in symptom management

Specialist palliative care consultation is a consideration when the patient’s symptoms are difficult to manage, no matter what the diagnosis or prognosis. For example, patients who require high doses of opioids pose a challenge for ICU clinicians who may have little experience with complex and escalating dosing regimens or side effect management. Choosing optimal primary and adjunctive therapies in the context of liver or renal failure is another example of symptom care that may be enhanced by specialist palliative care consultation.

How can symptom care be systematized for improvement?

The SCCM has published clinical practice guidelines based on best available evidence for pain, agitation, and delirium [7]. Yet, as the SCCM acknowledged, “closing the gap between the evidence highlighted in these guidelines and ICU practice will be a significant challenge for ICU clinicians and is best accomplished using a multifaceted, interdisciplinary approach” [7]. In some ICUs, structured approaches have been used with success to improve pain assessment and treatment [6, 88, 89]. For example, one ICU [89] tested a group of interventions to improve pain: (1) clinician education on the importance of standardizing methods of pain evaluation and treatment; (2) incorporation in every bedside medical record of a VAS for pain assessment; (3) implementation of house staff reporting of pain scores on daily ICU rounds; (4) interdisciplinary collaboration to develop a plan of care when pain scores above a specified threshold indicated an adverse event comparable to a medication error. The percentage of 4-h patient–nurse intervals in which nurses documented pain scores increased from 42 to 71 %, and the percentage of pain scores 3 or less on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (maximum pain) increased from 59 to 97 %. The investigators emphasized the contribution of the ICU staff to the development of the specific interventions, the simplicity and feasibility of these interventions, the attention to work process efficiency (specifically, making the pain assessment tools consistently available at the bedside), the accountability provided by continuing measurement and feedback of performance, and the attitudinal shift about analgesic practice that was fostered across the ICU team.

In another study [6], nurses reported pain assessments on daily rounds with physicians, and alerted the physician promptly when a patient’s pain or agitation exceeded specified levels. Attending physicians, house officers, and nurses received verbal and written educational materials, such as pocket cards with assessment scales, and a laminated poster of the pain scale was placed on the wall of each patient room. After implementation, the investigators observed significant decreases in the incidence of pain (63 to 42 %) and agitation (29 to 12 %) along with a decrease in reports of severe pain and agitation. The duration of mechanical ventilation and rate of nosocomial infections were both significantly reduced in the intervention group, and the proportion of nurses who were satisfied with the management of pain and sedation was dramatically increased. Although focused primarily on symptom assessment, the interdisciplinary approach of this initiative appeared to enhance the timeliness of physicians’ responses and allowed closer titration of analgesics and sedatives, including both increases and decreases in dosing, based on improvements in the nurses’ assessments.

An improvement effort addressing symptom management and assessment can be organized in the same way that has been recommended for improving ICU palliative care and other areas of critical care practice [81, 82, 90]. Key elements, which we have previously described [90], are set forth in Table 5. Success in achieving organizational change is more likely if supported by “champions”, who ideally are individuals with authority and respect in the ICU and institution. At the same time, enduring change appears to depend on design of work systems and processes that facilitate delivery of high-quality care [52, 91]. Examples include the use of “preprinted and/or computerized protocols and order forms, and quality ICU rounds checklists to facilitate the use of pain…management guidelines…”, as recently recommended by SCCM and others [52, 92]. As another example that is analogous to use of preoperative “time outs” to promote safety, a protocol for an invasive procedure could require that both the nurse and physician agree on the adequacy of preemptive analgesia before proceeding. The regular agenda for rounds might be modified to begin with presentation of symptom scores and related issues [6], such as the targeted level of symptom control, with documentation on a daily goals sheet [93]. If a palliative care consultant or service is available in the hospital, the ICU might implement a screen to identify patients with complex or refractory symptom issues who could benefit from specialist input [94]. Inclusion of all disciplines in development of system and process supports is necessary. Shadowing of clinicians during symptom assessment and management processes can help identify obstacles and suggest steps to a more efficient and effective process [95].

Measuring quality of care

In parallel with processes of care designed to improve symptom assessment and management, data should be captured to assess the quality of care. Specified measures are available to evaluate the quality of care related to pain and dyspnea in the ICU (see Table 6). For example, the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality posted measures 0 [2] focusing on the proportion of 4-h nurse–patient care intervals in which pain is assessed. Measures of respiratory distress were proposed on the basis of literature review and expert consensus by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care Peer Workgroup [96]. A consensus of experts convened by the American College of Chest Physicians recommended periodic review of patient and family satisfaction with symptom treatment, “bearing in mind that patients often report satisfaction with pain treatment despite experiencing severe pain, a high incidence of side effects, and inadequate pain treatment” [52]. This expert group also recommended surveying physicians and nurses for satisfaction to provide insight into aspects of care warranting further change. In choosing measures, ICUs should carefully consider feasibility of data collection, since few units will have resources for a complex or large-scale measurement effort, and most will have other improvement projects that compete for resource allocation. To reduce burden in their project to improve pain assessment and management, leaders in one ICU [89] limited data collection to a random subset of ICU patients at selected intervals. In addition, while ongoing evaluation is an essential component, measurement alone will not improve care but must be coupled with well-designed interventions to achieve better performance [97]. Finally, it is important to monitor for the emergence of unintended adverse effects of new processes of care [89], such as an unacceptable burden on staff, or an increase in duration of mechanical ventilation, alterations in patient mental status, or constipation, that might be thought to result from changes in symptom strategies.

Conclusion

An important goal for improving ICU palliative care is to not only promote patient comfort but to support other favorable outcomes of intensive care that are associated with symptom control. Pain, dyspnea, and thirst are prevalent symptoms that produce patient distress. We offer valid and reliable symptom assessment methods to meet the specific communication and cognitive abilities of critically ill patients in order to gain as much knowledge as possible of the patient’s experience. Treatment of pain, dyspnea, and thirst entails an array of techniques that must be appropriate to the source, or anticipated source, of the symptom, the condition of the patient, and the goals of care. The concerted, collaborative efforts of the entire ICU clinical team—physicians, nurses, and therapists—aided by input and support from patients and families will help close the gap between evidence and practice for treating distressing symptoms.

References

Nelson JE, Puntillo KA, Pronovost PJ, Walker AS, McAdam JL, Ilaoa D, Penrod J (2010) In their own words: patients and families define high-quality palliative care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 38:808–818

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services (2013) Intensive care unit (ICU) palliative care. http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id=28311&search=palliative+care. Accessed 22 Oct 2013

Swinamer DL, Phang PT, Jones RL, Grace M, King EG (1988) Effect of routine administration of analgesia on energy expenditure in critically ill patients. Chest 93:4–10

Karaman S, Kocabas S, Uyar M, Zincircioglu C, Firat V (2006) Intrathecal morphine: effects on perioperative hemodynamics, postoperative analgesia, and stress response for total abdominal hysterectomy. Adv Ther 23:295–306

Lewis KS, Whipple JK, Michael KA, Quebbeman EJ (1994) Effect of analgesic treatment on the physiological consequences of acute pain. Am J Hosp Pharm 51:1539–1554

Chanques G, Jaber S, Barbotte E, Violet S, Sebbane M, Perrigault PF, Mann C, Lefrant JY, Eledjam JJ (2006) Impact of systematic evaluation of pain and agitation in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 34:1691–1699

Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, Ely EW, Gelinas C, Dasta JF, Davidson JE, Devlin JW, Kress JP, Joffe AM, Coursin DB, Herr DL, Tung A, Robinson BR, Fontaine DK, Ramsay MA, Riker RR, Sessler CN, Pun B, Skrobik Y, Jaeschke R (2013) Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 41:263–306

Mahler DA, Selecky PA, Harrod CG, Benditt JO, Carrieri-Kohlman V, Curtis JR, Manning HL, Mularski RA, Varkey B, Campbell M, Carter ER, Chiong JR, Ely EW, Hansen-Flaschen J, O’Donnell DE, Waller A (2010) American College of Chest Physicians consensus statement on the management of dyspnea in patients with advanced lung or heart disease. Chest 137:674–691

Parshall MB, Schwartzstein RM, Adams L, Banzett RB, Manning HL, Bourbeau J, Calverley PM, Gift AG, Harver A, Lareau SC, Mahler DA, Meek PM, O’Donnell DE (2012) An official American Thoracic Society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185:435–452

Puntillo KA (1990) Pain experiences of intensive care unit patients. Heart Lung 19:526–533

Gelinas C (2007) Management of pain in cardiac surgery ICU patients: have we improved over time? Intensive Crit Care Nurs 23:298–303

Nelson JE, Meier DE, Oei EJ, Nierman DM, Senzel RS, Manfredi PL, Davis SM, Morrison RS (2001) Self-reported symptom experience of critically ill cancer patients receiving intensive care. Crit Care Med 29:277–282

Puntillo KA, Arai S, Cohen NH, Gropper MA, Neuhaus J, Paul SM, Miaskowski C (2010) Symptoms experienced by intensive care unit patients at high risk of dying. Crit Care Med 38:2155–2160

Schmidt M, Demoule A, Polito A, Porchet R, Aboab J, Siami S, Morelot-Panzini C, Similowski T, Sharshar T (2011) Dyspnea in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 39:2059–2065

Puntillo KA, White C, Morris AB, Perdue ST, Stanik-Hutt J, Thompson CL, Wild LR (2001) Patients’ perceptions and responses to procedural pain: results from Thunder Project II. Am J Crit Care 10:238–251

Puntillo KA (1994) Dimensions of procedural pain and its analgesic management in critically ill surgical patients. Am J Crit Care 3:116–122

Campbell ML (2012) Dyspnea prevalence, trajectories, and measurement in critical care and at life’s end. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 6:168–171

Mularski RA, Campbell ML, Asch SM, Reeve BB, Basch E, Maxwell TL, Hoverman JR, Cuny J, Clauser SB, Snyder C, Seow H, Wu AW, Dy S (2010) A review of quality of care evaluation for the palliation of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181:534–538

Puntillo K, Weiss SJ (1994) Pain: its mediators and associated morbidity in critically ill cardiovascular surgical patients. Nurs Res 43:31–36

Puntillo K, Ley SJ (2004) Appropriately timed analgesics control pain due to chest tube removal. Am J Crit Care 13:292–301

Arai S, Cooper B, Nelson JE, Stotts N, Puntillo K (2012) A thirst intervention bundle decreases the distress of ICU patients’ thirst. Crit Care Med 40(12) (abstract no. 124)

Chanques G, Viel E, Constantin JM, Jung B, de Lattre S, Carr J, Cisse M, Lefrant JY, Jaber S (2010) The measurement of pain in intensive care unit: comparison of 5 self-report intensity scales. Pain 151:711–721

Gift A (1989) Validation of a vertical visual analogue scale as a measure of clinical dyspnea. Rehabil Nurs 14:323–325

Chang VT, Hwang SS, Kasimis B, Thaler HT (2004) Shorter symptom assessment instruments: the Condensed Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (CMSAS). Cancer Invest 22:526–536

Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K (1991) The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 7:6–9

Radtke JV, Baumann BM, Garrett KL, Happ MB (2011) Listening to the voiceless patient: case reports in assisted communication in the intensive care unit. J Palliat Med 14:791–795

Payen JF, Bru O, Bosson JL, Lagrasta A, Novel E, Deschaux I, Lavagne P, Jacquot C (2001) Assessing pain in critically ill sedated patients by using a behavioral pain scale. Crit Care Med 29:2258–2263

Gelinas C, Fillion L, Puntillo KA, Viens C, Fortier M (2006) Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool in adult patients. Am J Crit Care 15:420–427

Puntillo KA, Morris A, Thompson CL, Stanik-Hutt J, White CA, Wild LR (2004) Pain behaviors observed during six common procedures: results from Thunder Project II. Crit Care Med 32:421–427

Campbell ML (2007) Fear and pulmonary stress behaviors to an asphyxial threat across cognitive states. Res Nurs Health 30:572–583

Campbell ML (2008) Psychometric testing of a respiratory distress observation scale. J Palliat Med 11:44–50

Campbell ML, Templin T, Walch J (2010) A respiratory distress observation scale for patients unable to self-report dyspnea. J Palliat Med 13:285–290

Nekolaichuk CL, Bruera E, Spachynski K, MacEachern T, Hanson J, Maguire TO (1999) A comparison of patient and proxy symptom assessments in advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med 13:311–323

Neighbor ML, Puntillo K, O’Neill B (1999) Nurse underestimation of patient pain intensity (abstract). Acad Emerg Med 6:514

Miaskowski C, Zimmer EF, Barrett KM, Dibble SL, Wallhagen M (1997) Differences in patients’ and family caregivers’ perceptions of the pain experience influence patient and caregiver outcomes. Pain 72:217–226

Ferrell BR, Grant M, Borneman T, Juarez G, ter Veer A (1999) Family caregiving in cancer pain management. J Palliat Med 2:185–195

Puntillo KA, Neuhaus J, Arai S, Paul SM, Gropper MA, Cohen NH, Miaskowski C (2012) Challenge of assessing symptoms in seriously ill intensive care unit patients: can proxy reporters help? Crit Care Med 40:2760–2767

Herr K, Coyne PJ, Key T, Manworren R, McCaffery M, Merkel S, Pelosi-Kelly J, Wild L (2006) Pain assessment in the nonverbal patient: position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain Manag Nurs 7:44–52

Puntillo K, Pasero C, Li D, Mularski RA, Grap MJ, Erstad BL, Varkey B, Gilbert HC, Medina J, Sessler CN (2009) Evaluation of pain in ICU patients. Chest 135:1069–1074

Payen JF, Chanques G, Mantz J, Hercule C, Auriant I, Leguillou JL, Binhas M, Genty C, Rolland C, Bosson JL (2007) Current practices in sedation and analgesia for mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a prospective multicenter patient-based study. Anesthesiology 106:687–695

Memis D, Inal MT, Kavalci G, Sezer A, Sut N (2010) Intravenous paracetamol reduced the use of opioids, extubation time, and opioid-related adverse effects after major surgery in intensive care unit. J Crit Care 25:458–462

Schmittner MD, Vajkoczy SL, Horn P, Bertsch T, Quintel M, Vajkoczy P, Muench E (2007) Effects of fentanyl and S(+)-ketamine on cerebral hemodynamics, gastrointestinal motility, and need of vasopressors in patients with intracranial pathologies: a pilot study. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 19:257–262

Payen JF, Genty C, Mimoz O, Mantz J, Bosson JL, Chanques G (2013) Prescribing nonopioids in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients. J Crit Care 28:534.e7–534.e12

Chanques G, Sebbane M, Constantin JM, Ramillon N, Jung B, Cisse M, Lefrant JY, Jaber S (2011) Analgesic efficacy and haemodynamic effects of nefopam in critically ill patients. Br J Anaesth 106:336–343

Maddali MM, Kurian E, Fahr J (2006) Extubation time, hemodynamic stability, and postoperative pain control in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery: an evaluation of fentanyl, remifentanil, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs with propofol for perioperative and postoperative management. J Clin Anesth 18:605–610

Erstad BL, Puntillo K, Gilbert HC, Grap MJ, Li D, Medina J, Mularski RA, Pasero C, Varkey B, Sessler CN (2009) Pain management principles in the critically ill. Chest 135:1075–1086

Pandey CK, Bose N, Garg G, Singh N, Baronia A, Agarwal A, Singh PK, Singh U (2002) Gabapentin for the treatment of pain in Guillain–Barre syndrome: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Anesth Analg 95:1719–1723

Pandey CK, Raza M, Tripathi M, Navkar DV, Kumar A, Singh UK (2005) The comparative evaluation of gabapentin and carbamazepine for pain management in Guillain–Barre syndrome patients in the intensive care unit. Anesth Analg 101:220–225

Pettersson PH, Jakobsson J, Owall A (2005) Intravenous acetaminophen reduced the use of opioids compared with oral administration after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 19:306–309

De Pinto M, Jelacic J, Edwards WT (2008) Very-low-dose ketamine for the management of pain and sedation in the ICU. J Opioid Manag 4:54–56

Prommer E (2010) Ketamine use in palliative care #132. http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_132.htm. Accessed 22 Oct 2013

Pasero C, Puntillo K, Li D, Mularski RA, Grap MJ, Erstad BL, Varkey B, Gilbert HC, Medina J, Sessler CN (2009) Structured approaches to pain management in the ICU. Chest 135:1665–1672

Banzett RB, Adams L, O’Donnell CR, Gilman SA, Lansing RW, Schwartzstein RM (2011) Using laboratory models to test treatment: morphine reduces dyspnea and hypercapnic ventilatory response. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184:920–927

Jennings AL, Davies AN, Higgins JP, Gibbs JS, Broadley KE (2002) A systematic review of the use of opioids in the management of dyspnea. Thorax 57:939–944

Currow DC, McDonald C, Oaten S, Kenny B, Allcroft P, Frith P, Briffa M, Johnson MJ, Abernethy AP (2011) Once-daily opioids for chronic dyspnea: a dose increment and pharmacovigilance study. J Pain Symptom Manag 42:388–399

Cepeda MS, Carr DB, Lau J, Alvarez H (2006) Music for pain relief. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD004843

(1992) Availability of clinical practice guidelines on acute pain management: operative or medical procedures and trauma and urinary incontinence in adults—AHCPR. Fed Regist 57:12829–12831

Curtis JR, Cook DJ, Sinuff T, White DB, Hill N, Keenan SP, Benditt JO, Kacmarek R, Kirchhoff KT, Levy MM (2007) Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in critical and palliative care settings: understanding the goals of therapy. Crit Care Med 35:932–939

Nava S, Ferrer M, Esquinas A, Scala R, Groff P, Cosentini R, Guido D, Lin CH, Cuomo AM, Grassi M (2013) Palliative use of non-invasive ventilation in end-of-life patients with solid tumours: a randomised feasibility trial. Lancet Oncol 14:219–227

Azoulay E, Kouatchet A, Jaber S et al (2013) Noninvasive mechanical ventilation in patients having declined tracheal intubation. Intensive Care Med 39:292–301

Azoulay E, Kouatchet A, Jaber S, Mexiani F, Papazian L, Brochard L, Demoule A (2013) Non-invasive ventilation for end-of-life oncology patients. Lancet Oncol 14:200–201

Barach AL (1974) Chronic obstructive lung disease: postural relief of dyspnea. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 55:494–504

Sharp JT, Drutz WS, Moisan T, Foster J, Machnach W (1980) Postural relief of dyspnea in severe chronic obstructive lung disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 122:201–211

Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, Casey DE, Cross JT, Owens DK, Dallas P, Dolan NC, Forciea MA, Halasyamani L, Hopkins RH (2008) Evidence-based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 148:141–146

Guyatt GH, McKim DA, Austin P, Bryan R, Norgren J, Weaver B, Goldstein RS (2000) Appropriateness of domiciliary oxygen delivery. Chest 118:1303–1308

Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Wilkinson A, Mularski RA, Morton SC, Hughes RG, Hilton LK, Maglione M, Rhodes SL, Rolon C, Sun VC, Shekelle PG (2008) Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 148:147–159

Cranston JM, Crockett A, Currow D (2008) Oxygen therapy for dyspnoea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD004769

Abernethy AP, McDonald CF, Frith PA, Clark K, Herndon JE 2nd, Marcello J, Young IH, Bull J, Wilcock A, Booth S, Wheeler JL, Tulsky JA, Crockett AJ, Currow DC (2010) Effect of palliative oxygen versus room air in relief of breathlessness in patients with refractory dyspnoea: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 376:784–793

Campbell ML, Yarandi H, Dove-Medows E (2013) Oxygen is non-beneficial for most patients who are near death. J Pain Symptom Manag 45:517–523

Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M, Kuhnbach R, Higginson IJ (2010) Effectiveness of a hand-held fan for breathlessness: a randomised phase II trial. BMC Palliat Care 9:22

Rocker G, Horton R, Currow D, Goodridge D, Young J, Booth S (2009) Palliation of dyspnoea in advanced COPD: revisiting a role for opioids. Thorax 64:910–915

Simon ST, Higginson IJ, Booth S, Harding R, Bausewein C (2010) Benzodiazepines for the relief of breathlessness in advanced malignant and non-malignant diseases in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD007354

Navigante AH, Cerchietti LC, Castro MA, Lutteral MA, Cabalar ME (2006) Midazolam as adjunct therapy to morphine in the alleviation of severe dyspnea perception in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag 31:38–47

Sironi O, Sbanotto A, Banfi MG, Beltrami C (2007) Midazolam as adjunct therapy to morphine to relieve dyspnea? J Pain Symptom Manag 33:233–234

Ship JA, McCutcheon JA, Spivakovsky S, Kerr AR (2007) Safety and effectiveness of topical dry mouth products containing olive oil, betaine, and xylitol in reducing xerostomia for polypharmacy-induced dry mouth. J Oral Rehabil 34:724–732

Cho EA, Kim KH, Park JY (2010) Effects of frozen gauze with normal saline and ice on thirst and oral condition of laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients: pilot study. J Korean Acad Nurs 40:714–723

Wiley SB (1969) Why glycerol and lemon juice? Am J Nurs 69:342–344

Van Drimmelen J, Rollins HF (1969) Evaluation of a commonly used oral hygiene agent. Nurs Res 18:327–332

Meurman JH, Sorvari R, Pelttari A, Rytomaa I, Franssila S, Kroon L (1996) Hospital mouth-cleaning aids may cause dental erosion. Spec Care Dent 16:247–250

Miller M, Kearney N (2001) Oral care for patients with cancer: a review of the literature. Cancer Nurs 24:241–254

Chanques G, Constantin JM, Sauter M, Jung B, Sebbane M, Verzilli D, Lefrant JY, Jaber S (2009) Discomfort associated with under humidified high-flow oxygen therapy in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 35:996–1003

Engstrom A, Soderberg S (2004) The experiences of partners of critically ill persons in an intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 20:299–308

Chien WT, Chiu YL, Lam LW, Ip WY (2006) Effects of a needs-based education programme for family carers with a relative in an intensive care unit: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Nurs Stud 43:39–50

Hammond F (1995) Involving families in care within the intensive care environment: a descriptive survey. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 11:256–264

McAdam JL, Arai S, Puntillo KA (2008) Unrecognized contributions of families in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 34:1097–1101

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Arich C, Brivet F, Brun F, Charles PE, Desmettre T, Dubois D, Galliot R, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Goldgran-Toledano D, Herbecq P, Joly LM, Jourdain M, Kaidomar M, Lepape A, Letellier N, Marie O, Page B, Parrot A, Rodie-Talbere PA, Sermet A, Tenaillon A, Thuong M, Tulasne P, Le Gall JR, Schlemmer B (2003) Family participation in care to the critically ill: opinions of families and staff. Intensive Care Med 29:1498–1504

Mitchell M, Chaboyer W, Burmeister E, Foster M (2009) Positive effects of a nursing intervention on family-centered care in adult critical care. Am J Crit Care 18:543–552

Gelinas C (2010) Nurses’ evaluations of the feasibility and the clinical utility of the critical-care pain observation tool. Pain Manag Nurs 11:115–125

Erdek MA, Pronovost PJ (2004) Improving assessment and treatment of pain in the critically ill. Int J Qual Health Care 16:59–64

Nelson J, Campbell ML, Cortez TB, Curtis JR, Lustbader DR, Mosenthal AC, Mulkerin C, Puntillo KA, Ray DE, Bassett R, Boss RD, Brasel KJ, Weissman DE (2010) Organizing an ICU palliative care initiative: a technical assistance monograph from the IPAL-ICU project. http://ipal-live.capc.stackop.com/downloads/ipal-icu-organizing-an-icu-palliative-care-initiative.pdf. Accessed 22 Oct 2013

Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Needham DM (2008) Translating evidence into practice: a model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ 337:a1714

Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, Sinopoli D, Chu H, Cosgrove S, Sexton B, Hyzy R, Welsh R, Roth G, Bander J, Kepros J, Goeschel C (2006) An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med 355:2725–2732

Pronovost P, Berenholtz S, Dorman T, Lipsett PA, Simmonds T, Haraden C (2003) Improving communication in the ICU using daily goals. J Crit Care 18:71–75

Gay EB, Weiss SP, Nelson JE (2012) Integrating palliative care with intensive care for critically ill patients with lung cancer. Ann Intensive Care 2:3

Gurses AP, Kim G, Martinez EA, Marsteller J, Bauer L, Lubomski LH, Pronovost PJ, Thompson D (2012) Identifying and categorising patient safety hazards in cardiovascular operating rooms using an interdisciplinary approach: a multisite study. BMJ Qual Saf 21:810–818

Mularski RA, Curtis JR, Billings JA, Burt R, Byock I, Fuhrman C, Mosenthal AC, Medina J, Ray DE, Rubenfeld GD, Schneiderman LJ, Treece PD, Truog RD, Levy MM (2006) Proposed quality measures for palliative care in the critically ill: a consensus from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation critical care workgroup. Crit Care Med 34:S404–S411

Nelson JE, Brasel KJ, Campbell ML, Cortez TB, Curtis JR, Lustbader DR, Mosenthal AC, Mulkerin C, Puntillo KA, Ray DE, Bassett R, Boss RD, Weissman DE (2010) Evaluation of ICU palliative care quality: a technical assistance monograph from the IPAL-ICU project. http://ipal-live.capc.stackop.com/downloads/ipal-icu-evaluation-of-icu-palliative-care-quality.pdf. Accessed 22 Oct 2013

Downie WW, Leatham PA, Rhind VM, Wright V, Branco JA, Anderson JA (1978) Studies with pain rating scales. Ann Rheum Dis 37:378–381

Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S (1986) The measurement of clinical pain intensity: a comparison of six methods. Pain 27:117–126

Reading AE (1980) A comparison of pain rating scales. J Psychosom Res 24:119–124

Nelson JE, Meier DE, Litke A, Natale DA, Siegel RE, Morrison RS (2004) The symptom burden of chronic critical illness. Crit Care Med 32:1527–1534

Futier E, Chanques G, Cayot Constantin S, Vernis L, Barres A, Guerin R, Chartier C, Perbet S, Petit A, Jabaudon M, Bazin JE, Constantin JM (2012) Influence of opioid choice on mechanical ventilation duration and ICU length of stay. Minerva Anestesiol 78:46–53

Chaveron D, Silva S, Sanchez-Verlaan P, Conil JM, Sommet A, Geeraerts T, Genestal M, Minville V, Fourcade O (2012) The 90% effective dose of a sufentanil bolus for the management of painful positioning in intubated patients in the ICU. Eur J Anaesthesiol 29:280–285

Oliverio C, Malone N, Rosielle DA (2012) Opioid use in liver failure #260. http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_260.htm. Accessed 22 Oct 2013

Arnold R, Verrico P, Davison SN (2009) Opioid use in renal failure #161. http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_161.htm. Accessed 22 Oct 2013

Wilson RK, Weissman DE (2006) Neuroexcitatory effects of opioids: patient assessment #057. http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_057.htm. Accessed 22 Oct 2013

Wilson RK, Weissman DE (2009) Neuroexcitatory effects of opioids: treatment #058. http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_058.htm. Accessed 22 Oct 2013

Schwartzstein RM, Lahive K, Pope A, Weinberger SE, Weiss JW (1987) Cold facial stimulation reduces breathlessness induced in normal subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis 136:58–61

Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR et al (2008) Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College [corrected] of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 36(3):953–963

Conflicts of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Puntillo, K., Nelson, J.E., Weissman, D. et al. Palliative care in the ICU: relief of pain, dyspnea, and thirst—A report from the IPAL-ICU Advisory Board. Intensive Care Med 40, 235–248 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-013-3153-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-013-3153-z