Abstract

Many older adults in our society suffer from loneliness – a painful, distressing feeling arising from the perception that one’s social connections are inadequate. When loneliness is experienced over prolonged periods of time, it can become devastating to older adults’ physical and mental health. Loneliness has been associated with depression, cognitive decline, and mortality. As the ageing population around the world grows in size and proportion, tackling late life loneliness is becoming a top priority in both ethical and economic terms. Previous studies have attempted to attribute late life loneliness to individual (micro) and social network (meso)-level characteristics. We argue that ageism at the societal (macro)-level – encompassing stereotypes, prejudices, and de facto discrimination against older adults – predisposes the older population to neglect, social isolation, and ultimately, loneliness. We propose three mechanisms whereby ageism may contribute to loneliness. First, chronic social rejection may incline older adults to avoid and withdraw from social participation. Second, individuals may self-embody the stereotypes of old age such as old age being a time of loneliness. The last path is an objective one, which emphasizes age-based discriminatory practices that increase social exclusion of older adults thereby increasing their risk of becoming lonely.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

9.1 Introduction

Europe is seeing unprecedented growth in the ageing population. The World Health Organization projects that from 2000 to 2050, the ageing population over 60 years will triple in size from 600 million to two billion (World Health Organization 2015). As this trend progresses, governments are faced with the ethical and moral imperative to ensure that older persons maintain a high quality of life as they age.

One of the major hazards to older people’s well-being is loneliness (de Jong Gierveld et al. 2016). Loneliness is the subjective, unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of companionship (De Jong Gierveld 1998). It is distinguished from social isolation; While the latter reflects an objective social situation characterized by lack of relationships with others (Dykstra 2009), loneliness is a marker of the quality of a person’s social interactions. As such, loneliness develops when one’s social relationships are not accompanied by the desired degree of intimacy (De Jong Gierveld 1998).

In recent years, interest in ageing and loneliness has grown for two primary reasons. First, loneliness is a socially prevalent phenomenon among old people. In a representative sample of British community-dwelling older adults, almost 40% reported experiencing some degree of loneliness (Victor et al. 2005). Similar prevalence rates were found in Finland among a random sample of people aged 75 and over (Savikko et al. 2005). In the United States, Theeke (2007) reports that approximately 17% of the people aged 50 and above reported feeling lonely. Chronic loneliness, afflicting individuals over prolonged periods of time, affects approximately 10% of older people (Harvey and Walsh 2016).

A second reason for the rising interest in late-life loneliness has to do with its detrimental effects to physical and mental health which have been recorded in numerous studies. In a population-based study (CHASRS), loneliness was found to be associated with elevated systolic blood pressure (Hawkley et al. 2006). Moreover, the researchers found loneliness to be a unique predictor of age-related increases in systolic blood pressure (Hawkley et al. 2006). Loneliness was also found to compromise cardiovascular health (Hawkley et al. 2003), and was identified as a significant risk factor for coronary heart conditions (Sorkin et al. 2002; Thurston and Kubzansky 2009). Furthermore, in a study carried out in the Netherlands among 2788 community-dwelling individuals aged between 55 and 85 years, peripheral vascular disease, lung disease, and arthritis were found to be associated with greater loneliness after adjusting for demographic variables and other diseases, such as stroke and cancer (Penninx et al. 1999). A prospective association between loneliness and mortality years later has been repeatedly reported in the literature (Holt-Lunstad et al. 2015; Luo et al. 2012; Shiovitz-Ezra and Ayalon 2010).

Along with its adverse effects on physical health, loneliness is also associated with poor mental health. In both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, greater loneliness has been associated with higher levels of depression even after taking into account central demographic and psychosocial factors (Cacioppo et al. 2006). Feelings of loneliness are positively associated with psychological distress (Constanca et al. 2006), hopelessness (Barg et al. 2006), serious thoughts of suicide and parasuicide (Stravynski and Boyer 2001), passive death wishes (Ayalon and Shiovitz-Ezra 2011), and negatively associated with emotional well-being (Lee and Ishii-Kuntz 1987).

Several studies, too, have noted the negative association between loneliness and cognition in later life. In a cross-sectional community based study, loneliness was found to be associated with impaired global cognition after adjusting for depression, social network and demographic characteristics (O’Luanaigh et al. 2012). In a longitudinal study conducted in Finland, loneliness at baseline predicted cognitive decline 10 years later (Tilvis et al. 2004). In accordance with these findings, in a prospective study conducted in the U.S., loneliness was found to be a robust risk factor for developing clinical Alzheimer’s disease, net of the effect of potential confounders including social isolation (Wilson et al. 2007). More recently, in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, loneliness at baseline was found to be associated with poorer cognitive functioning, measured by immediate and delayed recall over a 4-year follow-up (Shankar et al. 2013).

The bio-physiological mechanisms whereby loneliness affects health are not yet well-understood, but growing evidence links loneliness to inflammation and metabolic deregulation. Loneliness was found to be associated with pro-inflammatory cytokine responses. In one study, lonelier participants showed elevated stimulated pro-inflammatory cytokine production in the presence of acute laboratory stress (Jaremka et al. 2013). In another study, loneliness was positively associated with IL-6 responses to acute laboratory psychological stress in an adjusted model that controlled for socioeconomic background and health behaviors among older women (Hackett et al. 2012). Loneliness was also independently associated with elevated HbA1c levels, a bio-marker of metabolic dysregulation (O’Luanaigh et al. 2012).

Considering the high prevalence of late-life loneliness and its deleterious effect on physical, mental and cognitive health, it is critical that we identify the risk factors associated with loneliness earlier in the trajectory of ageing so that appropriate public policy may be put in place to address the issue. One significant, albeit under-studied, risk factor for late-life loneliness is ageism – stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination against older persons. Below, we review loneliness and ageism separately. Following, we outline the pathways whereby ageism may contribute to late life loneliness, and bring initial evidence supporting the claims.

9.2 Loneliness

Loneliness is a subjective marker for deficits in one’s social relationships and interactions. These social deficits manifest in terms of both quantity (i.e., limited social interactions or absence of social interactions), and more importantly, quality (i.e., lack of intimacy, reliable alliance, and attachment; De Jong Gierveld 1998; Perlman 2004). Loneliness is characterized as a painful, distressing, and unpleasant experience (Peplau and Perlman 1982) deriving from a perceived discrepancy between desired and actual social connections. According to the cognitive discrepancy model, feelings of loneliness arise when there is a mismatch between what individuals want, need, or desire on the one hand, and their actual social relations on the other hand. Predisposing factors include cultural norms as well as precipitating events such as chronic conditions and widowhood, which become more prevalent in old age and potentially contribute to a gap between one’s desired and existing social environment. However, a perceived mismatch does not necessarily entail loneliness. Several cognitive processes of evaluation mediate between the perceived mismatch and feelings of loneliness. These processes include causal attributions, social comparisons, and perceived control. Past experience and the experience of other people in the social environment shape this evaluation process. Therefore, people vary in the way they interpret and react to their social circumstances.

Contrary to other theoretical views of loneliness, such as the social needs approach (represented by Weiss 1973, 1987), the cognitive discrepancy model of loneliness suggests an indirect relationship between objective deficits in one’s social network and feelings of loneliness, which is mediated by cognitive processes of perception and evaluation (De Jong Gierveld 1998; Perlman and Peplau 1998; Peplau and Perlman 1982). Therefore, loneliness is only associated with deficits in one’s objective social situation, but is not synonymous with the circumstances of that situation. For example, people can feel lonely in the company of many others (“lonely in the crowd”), or they can be alone for long periods of time without feeling lonely. Objective isolation does not lead to loneliness when the desired level of social relations is low; being alone is voluntary, or when the social situation is attributed to external factors beyond one’s control (Perlman 2004).

Similarly, the evolutionary theory of loneliness (Cacioppo et al. 2015a) views loneliness as an aversive signal deriving from a discrepancy between desired and actual social relationships, which motivates people to socially engage and reconnect. According to this perspective, loneliness plays a key role in the evolution of humanity, because reconnection with others is crucial for survival and reproduction (Goossens et al. 2015). The evolutionary theory argues that loneliness is similar to other biological needs such as hunger, in that it creates significant feelings of discomfort that motivate individuals to take action and extricate themselves from the painful and distressing experience.

Recently, a review of the ontogeny of loneliness has differentiated between environmental triggers of loneliness across the life span (Qualter et al. 2015). It was suggested that as of adolescence, romantic relationships become increasingly important, and that compromised quality of that type of relationship is mostly related to loneliness. This relationship is also evident throughout adulthood, including early adulthood and mid-life, when poor quality of marriage has been found to explain loneliness. Similarly, marital quality and life partnership fulfill needs for belonging in old age. However, at this stage of life these needs are challenged as widowhood, illness, and reduced social activities become sources of loneliness (Qualter et al. 2015).

Previous studies have mostly attempted to attribute late life loneliness to individual (micro) and social network (meso)-level characteristics (Ayalon et al. 2016; Kahn et al. 2003; Shiovitz-Ezra 2013). However, restricted opportunities for meaningful social participation in old age may bring about feelings of loneliness. The following section explores how ageism, including stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination against older persons may lead to late-life loneliness.

9.3 Ageism

We live in a society that glorifies youth and dreads old age. We are deeply disturbed by the appearance of a new wrinkle adorning our face; we balk at the sight of our ever-expanding forehead gnawing higher and higher at our hairline. Both are reminders of the incontrovertible truth that we are getting older. A 140.3 billion-dollar anti-ageing industry capitalizes on these anxieties, selling the public the products – and promise – to hold off wrinkling, blur pigmentation, eliminate excess fat, and restore the growth of youthful hair (Zion Market Research 2016).

But people’s concerns about ageing go beyond the cosmetic. The imminent threats of sickness, disability, cognitive deterioration, loss of independence, and death, hang over the prospect of old age. Tremendous efforts on the side of scientists and pharmaceutical companies are made to discover new means to influence the physiological pathways leading to biological ageing, hoping to set back the clock, or at least slow it down. Our relentless efforts to hold off ageing and the sentiments they feed on speak volumes about how we, as a society, regard ageing (one famous gerontologist characterized these sentiments as “dread, discomfort, and denial”, Butler 1980, p. 10).

Not only are we disgruntled with our own ageing process, we also harbor ambivalent attitudes towards older people at large. Changes in societal structure over the past few centuries have rendered older adults “marginalized, institutionalized, and stripped of responsibility [and] power” (Nelson 2005, p. 208). The industrial revolution, which brought about increased mobility for workers, also in so doing contributed to the disintegration of the extended family structure. As a result, grandparents no longer lived with their families. In the light of technological advances, older people’s work experience became outdated, and their work obviated. Simultaneous advances in medicine extended people’s lives, and as the older population grew in size, they came to be regarded as non-contributing burdens on society (Nelson 2005).

A recent large-scale linguistic analysis encompassing two centuries of written American English has found that stereotypes of older adults have grown increasingly negative over the years (having started out slightly positive in the 1800s; Ng et al. 2015). The study found that negativity towards older adults has grown in step with their relative share within society, presumably due to concerns of the younger generation that older adults act as a drain on economic resources (Ng et al. 2015). Complicating matters still, these concerns are not completely unfounded; with fertility rates falling and lifespans extending in recent years, the retired population is growing larger and larger in proportion to the employed sector, and it is expected that care for older adults – formal and informal – will impose a heavy cost on society (Suzman and Beard 2011).

Negative attitudes towards older adults, including stereotypes, prejudices, and de facto discrimination based on age, have been termed Ageism. Butler (1980, p. 10) identified three societal problems posed by ageism: “(1) Prejudicial attitudes toward the aged, toward old age, and toward the aging process, including attitudes held by the elderly themselves; (2) discriminatory practices against the elderly, particularly in employment, but in other social roles as well; and (3) institutional practices and policies which, often without malice, perpetuate stereotypic beliefs about the elderly, reduce their opportunities for a satisfactory life and undermine their personal dignity.” (p. 8).

9.3.1 The Stereotypes of Ageing

What are the major stereotypes that people harbor about ageing? To answer this question, researchers have asked participants to note the typical traits that came to their minds when they thought about old people (regardless of whether they believed them to be accurate or not). Collectively, these studies have yielded seven general stereotypes, four negative and three positive, shared by people of all ages about older adults: Severely Impaired; Despondent; Shrew/Curmudgeon; Recluse; Golden Ager; Perfect Grandparent; and John Wayne Conservative (Hummert 2011).

A complementary approach to age stereotyping relates the stereotypes of older adults to their perceived status within society. According to the Stereotype Content Model (Cuddy and Fiske 2002; Cuddy et al. 2005) two core dimensions jointly determine the content of stereotypes applied to groups within society: those of “competence (e.g., independent, skillful, confident, able)” and “warmth (e.g., good-natured, trustworthy, sincere, friendly)” (Cuddy and Fiske 2002, p. 8). Of the possible constellations of the two dimensions, older adults occupy a quadrant defined by low competence and high warmth, or as Cuddy and Fiske (2002) put it, ‘doddering, but dear’. Other groups that fall in this cluster include retarded and disabled people (Fiske et al. 2002). The prejudices most commonly elicited by people in this quadrant include pity and sympathy (Fiske et al. 2002). The structural relationships within society that antecede the competence and warmth dimensions are status and competition; perceptions of a group as high status indicate its competence, while its perceived competitiveness designates it as cold (Fiske et al. 2002). Accordingly, people tend to see older adults as lower-status and relatively uncompetitive (Fiske et al. 2002). A meta-analysis encompassing decades of research on attitudes towards older adults confirms that old people are generally perceived more stereotypically, as less attractive and as less competent than younger adults (Kite et al. 2005). What is more, it was found that people tended to behave less favorably towards older, as compared to younger adults (ibid). In sum, evaluations towards older people are somewhat ambivalent, with a negative predominance.

9.3.2 Neglect and Social Exclusion

What kind of behaviors derive from the stereotypes (doddering, but dear) and prejudices (pity and sympathy) towards older adults? Cuddy et al. (2007) found that perceived warmth of a group correlated with behavioral tendencies of helping, presumably mediated by pity, while perceived incompetence correlated with tendencies to neglect. This observation, once again, highlights the ambivalent nature of attitudes towards older adults. Older people are targets for help and sympathy, and at the same time are often neglected and socially excluded. Two major arenas where ageist practices are widespread are the health-care system (Ben-Harush et al. 2016) and the labor market (Pasupathi and Löckenhoff 2002). In both fields ageist beliefs and attitudes can join and become institutionalized forms of discriminatory norms and practices that intensify social exclusion of older adults. One prominent example from the labor market is mandatory retirement that occurs at a certain age without any consideration of whether the older worker prefers to continue working and contribute in the professional domain. Ending the working phase has many adverse consequences, including the narrowing of social network size (greater details about the retirement–social exclusion-loneliness relation will be provided later in this chapter).

Studies show that age-based discrimination is widespread. In the United States, 29.1% of adults 52 years and older in a sample of 4818 individuals reported being discriminated against on a range of interpersonal and medical issues, including being treated with disrespect, being threatened, and receiving worse medical services, based on their age (Rippon et al. 2015). In the UK, 34.8% of a sample of 7478 respondents reported being discriminated against (Rippon et al. 2015). Across 28 European countries, about a quarter of adults 62 years and older reported being discriminated against based on their age, treated with prejudice, with disrespect or treated badly because of their advanced age (van den Heuvel and van Santvoort 2011).

9.4 Pathways from Ageism to Loneliness

So far we have examined the phenomenon of ageism, as well as the content of ageing stereotypes and their societal roots. We have also seen some ways in which older people are discriminated against, presumably as a result of widespread ageism. As mentioned earlier, nowadays, one of the major difficulties faced by older adults is social exclusion and loneliness. The following section will sketch out how negativity towards older adults may contribute to social exclusion and loneliness.

9.4.1 Social Rejection

One psychological theory accounts for how discrimination against older adults could result in their progressive withdrawal from social participation and growing feelings of loneliness. Smart Richman and Leary (2009) propose a model for how humans, in general, respond to discrimination and stigmatization. While the model has yet to be applied to older adults, its relevance will briefly become apparent.

“[T]he psychological core of all instances in which people receive negative reactions from other people is that they represent, to varying degrees, threats to the goal of being valued and accepted by other people.” (Smart Richman and Leary 2009, p. 373) According to the theory, the primary emotion evoked by feeling socially devalued, unwanted and rejected is hurt. Smart Richman and Leary report on a study of emotional word associations (Storm and Storm 1987) which found that feelings of hurt are most strongly associated the terms neglected, rejected, unwanted, unwelcome, betrayal, misunderstood, different and isolated.

Following a rejection episode, people typically feel three sets of motives which may promote competing behaviors: (1) a desire for social connection; (2) antisocial aggressive or defensive urges, and (3) a drive to withdraw in order to avoid further rejection. What determines which motive will win out is the affected person’s construal of the rejection event. According to the theory, rejection that is experienced chronically over a prolonged period of time will increase the likelihood of withdrawal and avoidance behaviors.

To the extent that elderly people experience discrimination often and for prolonged periods of time (as indeed has been found, see the sections above), they would be expected to respond with behavioral avoidance, and to forego social participation opportunities. The hypothesis has yet to be directly tested. However, two studies give initial credence to the logic of discrimination-induced withdrawal in older adults.

Coudin and Alexopoulos (2010) asked older adults to read a text passage, ostensibly in order to gauge their language comprehension. The text was said to be taken from a speech in a gerontology conference, and its content was manipulated so as to include either positive, negative, or neutral portrayals of older adults. Subsequently the participants completed a questionnaire measuring their social and emotional loneliness (adapted from the UCLA Loneliness Scale, a well-known loneliness scale, Russel 1996). The authors found that the older adults who read the negative text subsequently reported feeling lonelier than those who had read the positive or neutral passages. Thus an experience of being negatively stereotyped can immediately lead a person to feel lonelier.

Sutin et al. (2015) explored the longitudinal relationship between perceived discrimination and subsequent loneliness in a nationally representative sample of adults 50 years and older in the American Health and Retirement Survey. The study followed 7622 participants (average age 67.5) over a 5 year period, measuring their baseline levels of everyday perceived discrimination and subsequent reports of loneliness. It was found that perceptions of discrimination based on age significantly predicted feelings of loneliness 5 years later (other types of discrimination had a similar effect). Age discrimination, like other forms of discrimination, can lead to feelings of loneliness that build up over time.

How do the experiences of ageism translate into feelings of loneliness? Vitman et al. (2014) demonstrate how ageism could lead to social exclusion of older adults in their neighborhood. In the study, younger adults in three neighborhoods in Tel Aviv, Israel completed questionnaires regarding attitudes towards older people. As a measure of social integration, older adults in the same neighborhoods indicated how often they participated in neighborhood activities, how familiar they are with neighbors, and to what degree they feel a ‘sense of neighborhood’. Regression analysis revealed that higher ageism in the neighborhood predicted reduced social integration. Encountering ageist attitudes in one’s neighborhood may lead to behavioral withdrawal and avoidance, in line with Smart Richman and Leary’s (2009) theory.

9.4.2 Stereotype Embodiment

Another pathway whereby ageism may affect loneliness is stereotype embodiment. Stereotype embodiment theory (Levy 2009) proposes that individuals absorb stereotypes present in their surrounding culture, giving rise to self-definitions that, in turn, affect functioning and health.

Various longitudinal studies have found that the endorsement of elderly stereotypes by ageing people themselves (called self-perceptions of ageing) foretell significant adverse effects to physical and mental functioning, sometimes decades down the line (Levy 2009). For example, one study, based on the Ohio Longitudinal Study of Aging and Retirement (utilizing data from 660 individuals) found that positive self-perceptions of ageing at baseline predicted survival rates more than 20 years later (Levy et al. 2002b). Self-perceptions of ageing were measured using items such as “Things keep getting worse as I get older” and “As you get older, you are less useful”. The effect of positive self-perceptions on survival remained significant even after controlling for baseline age, socioeconomic status, functional health, and loneliness. Another study (Levy et al. 2002a) based on a similar dataset found that positive self-perceptions of ageing at baseline were related to better functional health more than two decades later, adjusting for baseline functional health, self-rated health, age, gender, race, and socioeconomic status.

Experimental studies have found that exposing older adults to ageing stereotypes affects their performance in a stereotype-consistent manner (Levy and Leifheit-Limson 2009). For example, priming older adults with negative stereotypes of physical functioning was found to degrade motor performance, while priming them with negative stereotypes of cognitive function led to decrements in memory performance. In other words, the stereotypes people assimilate from the surrounding culture and identify with may act as self-fulfilling prophecies.

Pikhartova et al. (2016) sought to explore whether late-life loneliness stereotypes can, too, become self-fulfilling prophecies. The study utilized data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. First, the authors identified participants who reported no feelings of loneliness at baseline. Subsequently, these participants’ endorsement of statements expressing (1) their expectation to become lonelier as they age, and (2) the stereotype that old age is a time of loneliness, were analyzed and related to levels of reported feelings of loneliness several years later. It was found that approximately a third of participants expected to become lonelier as they aged, and about a quarter of the sample endorsed the stereotype that old age is a time of loneliness. In addition, it was found that both expectations and stereotypes of loneliness in old age predicted feelings of loneliness several years ahead, even after controlling for measures of social inclusion and a host of other demographic variables. In other words, this study found that harboring expectations and stereotypes of old-age loneliness – even when one is presently not feeling lonely – could act as self-fulfilling prophecies.

And yet, evidence that loneliness stereotypes operate as self-fulfilling prophecies is equivocal. One longitudinal study investigated the link between expectations of loneliness on the one hand and loneliness, new friendships, and perceived social support on the other (Menkin et al. 2016). The data were taken from the Baltimore Experience Corps Trial, a longitudinal volunteer intervention for older adults. The participants, 424 Baltimore residents age 60 and older, were randomly assigned either to an intervention group, who was to provide academic support to elementary school students, or to a control group that received information on other volunteer opportunities. At baseline, the participants answered a questionnaire measuring expectations regarding ageing. One and two years later, the participants completed measures of new friendships forged, perceived and desired social support, and loneliness. The expectations about ageing measure included subscales pertaining to physical health, mental health, and cognitive function. One of the mental health included items regarding expectations of loneliness, such as “Being lonely is just something that happens when people get old”.

The researchers found that positive expectations about ageing at baseline predicted more new friends 2 years later, including close friendships. In addition, it was found that baseline positive expectations predicted less desire for additional social support 12 months later. However, expectations regarding loneliness at baseline did not predict feelings of loneliness at follow-up.

9.4.3 Social Exclusion

Widely held ageist beliefs and attitudes can coalesce and become institutionalized forms of discriminatory norms and practices. Society-wide ageist norms and practices can, in turn, act as barriers to older adults’ active participation in social activities. Here we briefly discuss three domains in which stereotypes, prejudices, and discrimination against older adults may result in reduced social participation, predisposing adults to late-life loneliness.

One prominent form of social exclusion is mandatory retirement. At a certain age, people are expected – sometimes pressured, or even forced – to retire (Pasupathi and Löckenhoff 2002). While some workers welcome retirement, retiring effectively cuts off a wellspring of social connections, opportunities, and meaning available on a day-to-day basis. Early retirement – which can be catalyzed by the experience of ageism at the workplace (Thorsen et al. 2012; von Hippel et al. 2013) – can be particularly pernicious to older adults’ cognition and mental health (Börsch-Supan and Schuth 2014). Börsch-Supan and Schuth (2014) found that retirement in general, and early retirement in particular, are associated with reductions in overall social network size, and that this reduction is mostly owing to the presence of fewer friends, colleagues, and other non-family contacts in one’s social network.

Early retirement is sometimes imposed on older adults, since finding a job and rejoining the workforce over a certain age is much more difficult. Several field studies have found that companies grossly under-respond to work applications made by older adults compared to equally capable younger peers (Neumark et al. 2017; Pasupathi and Löckenhoff 2002). Older workers are perceived to be reliable and loyal, but at the same time, as less productive, less energetic, technologically savvy, or trainable than younger workers (reviewed in Swift et al. 2017, p. 206). Further impediments to hiring older workers include perceptions that older adults demand higher salaries and incur increased training and health care costs (ibid).

Finally, retirement – whether voluntary or forced – is accompanied by a reduction in income, which can compromise older people’s ability to afford participating in activities they enjoy (World Health Organization 2007, p.38). Indeed, low income has been pinpointed as a strong predictor of loneliness in old age (Luhmann and Hawkley 2016).

Another domain in which older people regularly experience prejudice and discrimination is healthcare. A review of the literature on age-differentiated behavior in the medical sphere has found that doctors often misdiagnose and disregard health complaints made by older adults, as well as emphasize disease management over disease prevention (Pasupathi and Löckenhoff 2002). These practices may stem from the underlying assumption that older adults’ health complaints are the inevitable result of advanced age, leading health professionals to overlook potential treatable causes for those complaints. As an example, cognitive deficits in older adults can be attributed – at least to some extent – to underlying depression. Attributing cognitive decline to aging alone may lead to older adults’ depression going unnoticed (ibid).

Neglect, misdiagnosis, and mistreatment of older adults may lead to deterioration in physical and mental health, as well as in mobility, thereby impeding social participation. Hawkley et al. (2008) have found that ill health, an inability to satisfy the desire to engage in social activity, and a small social network (among other risk factors) jointly contribute to older adults’ risk of late-life loneliness.

Finally, an inconspicuous feature of society that covertly discriminates against older adults and impedes social participation has to do with the design of the living environment. A survey conducted among older city dwellers around the world by the World Health Organization found some of the following features as barriers to social participation: inaccessibility to social activities due to distance and lack of or inconvenient transportation, inaccessibility of buildings, and lack of facilities such as toilets and rest areas (World Health Organization 2007). Some of the respondents in the survey voiced the belief that the living environment was not designed with older people’s needs in mind. Such inconspicuous features of the living environment, such as narrow or cracked sidewalks, lack of resting areas, insufficient lighting, and unclear bus route signs, can severely diminish older adults’ ability to remain physically and socially active.

9.5 Conclusions

Cumulative evidence attests to the negative consequences of loneliness. Its high prevalence among the older adult population alongside the deleterious effects on physical, emotional and cognitive health have urged an extensive exploration of its robust risk factors. Such studies, however, predominately have explored factors at the micro and meso levels. At the micro level, background factors such as gender, marital status, socio-economic status and health state are frequently being addressed as well as experiencing life-time traumatic events (Palgi et al. 2012). Examples for potential risk factors at the meso level are characteristics of one’s social network (Shiovitz-Ezra 2013). The quantitative domain but mainly the qualitative nature of one’s close social relationships have been found to predict late-life loneliness. Much less attention, however, has been given to the macro-cultural level, i.e. the way older people are being negatively perceived and the restricted social opportunities that are available for them to act socially.

The current chapter highlights the macro-cultural level by addressing the potential pathways from ageism to later-life loneliness and social exclusion. We overview two theoretical perspectives by which age negative perceptions and age discrimination potentially lead to feelings of loneliness. The “social rejection” model points to the negative feelings of being undesired, unwanted, betrayed and socially rejected that could lead to social withdrawal. The “stereotype embodiment” theory focused on self-fulfilling prophecies. Older people internalize the prevalent age related negative stereotypes and act accordingly. For example, when one’s expect to be lonely at old age and when old age is perceived as a lonely time it seems to become a reality. Another mechanism stresses how ageist practices restrict social opportunities for older adults, leading to reduced social engagement, and increased late-life loneliness. Studies have provided some support for these theoretical assumptions but this territory is yet insufficiently explored. Future research, for instance, should address ageism as a significant risk factor for late-life loneliness in a multi-level analysis where the Micro, Meso and Macro levels are taken into account. The unique contribution of each of these levels to loneliness experienced in old age is highly important in formulating causal process of developing loneliness.

A thorough exploration of risk factors is not merely important in the theoretical sense of gathering a better understanding of the loneliness phenomenon. It is also crucial in order to combat deleterious phenomena such as loneliness. The literature on interventions aimed at preventing and coping with loneliness lays out four strategies: (a) improving social skills; (b) enhancing social support; (c) increasing opportunities for social contact; and (d) addressing maladaptive social cognition. Among these the latter was found to be the most successful intervention strategy (Masi et al. 2011). Most recently, it has been proposed that integrated interventions which combine (social) cognitive behavioral therapy with short-term adjunctive pharmacological treatments are most effective in combating loneliness (Cacioppo et al. 2015b).

We would like to challenge the notion that puts heavy weight on the individual level when trying to minimize late-life loneliness. Three of the above mentioned strategies deal with compromised social skills, maladaptive social cognition and medical treatment for individuals who suffer from loneliness. Therefore, all three locate the risk factors in the individual. Another strategy looked at the meso level by addressing lack of social support. Only one strategy of dealing with loneliness looked at the social opportunities available for older adults and called for increasing the opportunity for social interactions. This is, however, only one step in taking into account the Macro-cultural level and in addressing ageism as one of the prime predictors of late-life loneliness. Increasing social opportunities does not deal with social rejection that might jeopardize any social contact. It also is not addressing the negative age-related stereotypes that might create a reality where stereotypes of weakness, incompetence and sickness become a fact and actively narrow older people’s social sphere.

Ageism is not easy to combat. It has profound psychological and sociological origins that shape the way people get older in a society that admires youth and anti-ageing. The deleterious effects of loneliness might give a significant incentive for policy makers and clinicians to develop and construct social plans that take into account the complexity of ageism. These “anti-ageism” plans should approach different arenas such as the education system (at all levels starting from kindergartens; see Requena et al. 2018; Chap. 23, in this volume) and the legal system (Doron et al. 2018; Chap. 19; Mikołajczyk 2018; Chap. 20; Georgantzi 2018; Chap. 21, in this volume). Decisive policy against ageism will potentially advance socially engaged older people and the perception of old age as a social and meaningful time.

References

Ayalon, L., & Shiovitz-Ezra, S. (2011). The relationship between loneliness and passive death wishes in the second half of life. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(10), 1677–1685.

Ayalon, L., Shiovitz-Ezra, S., & Roziner, I. (2016). A cross-lagged model of the reciprocal associations of loneliness and memory functioning. Psychology and Aging, 31(3), 255–261.

Barg, F. K., Huss-Ashmore, R., Wittink, M. N., Murray, G. F., Bogner, H. R., & Gallo, J. J. (2006). A mixed-methods approach to understanding loneliness and depression in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(6), S329–S339.

Ben-Harush, A., Shiovitz-Ezra, S., Doron, I., Alon, S., Golander, H., Lebovitsh, A., Haron, Y., & Ayalon, L. (2016). Ageism among physicians, nurses and social workers: Findings from a qualitative research. European Journal of Ageing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0389-9

Börsch-Supan, A., & Schuth, M. (2014). Early retirement, mental health, and social networks. In D. A. Wise (Ed.), Discoveries in the Economics of Aging (pp. 225–255). Chicago: Chicago Press.

Butler, R. N. (1980). Ageism: A foreword. Journal of Social Issues, 36(2), 8–11.

Cacioppo, J. T., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2006). Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging, 21(1), 140–151.

Cacioppo, J. T., Cacioppo, S., Cole, S. W., Capitanio, J. P., Goossens, L., & Boomsma, D. I. (2015a). Loneliness across phylogeny and a call for comparative studies and animal models. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 202–212.

Cacioppo, J. T., Grippo, L., Goossens, L., & Cacciopo, S. (2015b). Loneliness clinical import and interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 238–249.

Constanca, P., Salma, A., & Shah, E. (2006). Psychological distress, loneliness and disability in old age. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 11(2), 221–232.

Coudin, G., & Alexopoulos, T. (2010). “Help me! I”m old!’ How negative aging stereotypes create dependency among older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 14(5), 516–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607861003713182

Cuddy, A. J., & Fiske, S. T. (2002). Doddering but dear: Process, content, and function in stereotyping of older persons. InAgeism: Stereotyping and prejudice against older persons (pp. 3–26). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cuddy, A. J., Norton, M. I., & Fiske, S. (2005). This old stereotype: The perveasiveness and persistence of older adults stereotype. Journal of Social Issues, 61(2), 267–285.

Cuddy, A. J., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2007). The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 631.

De Jong Gierveld, J. (1998). A review of loneliness: Concept and definitions, determinants and consequences. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 8, 73–80.

de Jong Gierveld, J, van Tilburg, T. G, & Dykstra, P. A. (2016). Loneliness and social isolation. In A. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (2nd ed., pp. 1–30). Cambridge University Press (forthcoming).

Doron, I., Numhauser-Henning, A., Spanier, B., Georgantzi, N., & Mantovani, E. (2018). Ageism and anti-ageism in the legal system: A review of key themes. In L. Ayalon & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism: Vol. 19. International perspectives on aging (pp. 303–320). Berlin: Springer.

Dykstra, P. A. (2009). Older adult loneliness: Myths and realities. European Journal of Ageing, 6(2), 91.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

Georgantzi, N. (2018). The European union’s approach towards ageism. In L. Ayalon & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism: Vol. 19. International perspectives on aging (pp. 341–368). Berlin: Springer.

Goossens, L., Van Roekel, E., Verhagen, M., Cacioppo, J. T., Cacioppo, S., Maes, M., & Boomsma, D. I. (2015). The genetics of loneliness: Linking evolutionary theory to genome-wide genetics, epigenetics, and social science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 213–226.

Hackett, R. A., Hamer, M., Endrighi, R., Brydon, L., & Steptoe, A. (2012). Loneliness and stress-related inflammatory and neuroendocrine responses in older men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(11), 1801–1809.

Harvey, B., & Walsh, C. (2016). Loneliness and ageing: Ireland. North and South Dublin: Institute of Public Health.

Hawkley, L. C., Burleson, M. H., Berntson, G. G., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2003). Loneliness in everyday life: Cardiovascular activity, psychosocial context, and health behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(1), 105–120.

Hawkley, L. C., Masi, C. M., Berry, J. D., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2006). Loneliness is a unique predictor of age-related differences in systolic blood pressure. Psychology and Aging, 21(1), 152–164.

Hawkley, L. C., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Masi, C. M., Thisted, R. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(6), S375–S384.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

Hummert, M. L. (2011). Age stereotypes and aging. In K. Warner Schaie & S. L. Willis (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (pp. 249–262). San Diego: Academic.

Jaremka, L. M., Fagundes, C. P., Peng, J., Bennett, J. M., Glaser, R., Malarkey, W. B., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2013). Loneliness promotes inflammation during acute stress. Psychological Science, 24(7), 1089–1097.

Kahn, J. H., Hessling, R. M., & Russell, D. W. (2003). Social support, health, and well-being amongolder adults: What is the role of negative affectivity? Personality and Individual Differences, 35, 5–17.

Kite, M. E., Stockdale, G. D., Whitley, B. E., & Johnson, B. T. (2005). Attitudes toward younger and older adults: An updated meta-analytic review. Journal of Social Issues, 61(2), 241–266.

Lee, G. R., & Ishii-Kuntz, M. (1987). Social interaction, loneliness, and emotional well-being among older adults. Research on Aging, 9(4), 459–482.

Levy, B. (2009). Stereotype embodiment: A psychosocial approach to aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(6), 332–336.

Levy, B. R., & Leifheit-Limson, E. (2009). The stereotype-matching effect: Greater influence on functioning when age stereotypes correspond to outcomes. Psychology and Aging, 24(1), 230.

Levy, B. R., Slade, M. D., Kunkel, S. R., & Kasl, S. V. (2002a). Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(2), 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.2.261

Levy, B. R., Slade, M. D., & Kasl, S. V. (2002b). Longitudinal benefit of positive self-perceptions of aging on functional health. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(5), P409–P417. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.5.P409

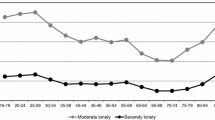

Luhmann, M., & Hawkley, L. C. (2016). Age differences in loneliness from late adolescence to oldest old age. Developmental Psychology, 52(6), 943.

Luo, Y., Hawkley, L. C., Waite, L. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2012). Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study. Social Science & Medicine, 74(6), 907–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.028

Masi, C. M., Chen, H. Y., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 219–266.

Menkin, J. A., Robles, T. F., Gruenewald, T. L., Tanner, E. K., & Seeman, T. E. (2016). Positive expectations regarding aging linked to more new friends in later life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 0(0), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbv118

Mikołajczyk, B. (2018). The council of europe’s approach towards ageism. In L. Ayalon & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism: Vol. 19. International perspectives on aging (pp. 321–339). Berlin: Springer.

Nelson, T. D. (2005). Ageism: Prejudice against our feared future self. Journal of Social Issues, 61(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00402.x

Neumark, D., Burn, I., & Button, P. (2017). Age discrimination and hiring of older workers. Age, 2017, 06.

Ng, R., Allore, H. G., Trentalange, M., Monin, J. K., & Levy, B. R. (2015). Increasing negativity of age stereotypes across 200 years: Evidence from a database of 400 million words. PLoS One, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117086

O’Luanaigh, C., O’Connell, H., Chin, A. V., Hamilton, F., Coen, R., Walsh, C., et al. (2012). Loneliness and vascular biomarkers: The Dublin healthy ageing study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(1), 83–88.

Palgi, Y., Shrira, A., Ben Ezra, M., Shiovitz Ezra, S., & Ayalon, L. (2012). Self- and other-oriented potential lifetime traumatic events as predictors of loneliness in the second half of life. Aging & Mental Health, 16(4), 423–430.

Pasupathi, M., & Löckenhoff, C. E. (2002). Ageist behavior. In Nelson (Ed.), Ageism: Stereotyping and prejudice against older persons (pp. 201–246). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Penninx, B. W., van Tilburg, T., Kriegsman, D. M., Boeke, A. J., Deeg, D. J., & van Eijk, J. T. (1999). Social network, social support, and loneliness in older persons with different chronic diseases. Journal of Aging and Health, 11(2), 151–168.

Peplau, L. A., & Perlman, D. (1982). Perspectives on loneliness. In L. A. Peplau & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 1–20). New York: Wiley.

Perlman, D. (2004). European and Canadian studies of loneliness among seniors. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, 23(02), 181–188.

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1998). Loneliness. Encyclopedia of Mental Health, 2, 571–581.

Pikhartova, J., Bowling, A., & Victor, C. (2016). Is loneliness in later life a self-fulfilling prophecy? Aging & Mental Health, 20(5), 543–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1023767

Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Harris, R., Van Roekel, E., Lodder, G., Bangee, M., et al. (2015). Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 250–264.

Requena, M. J., Swift, H., Naegele, L., Zwamborn, M., Metz, S., Bosems, W. P. H., & Hoof, J. (2018). Educational methods using intergenerational interaction to fight ageism. In L. Ayalon & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism: Vol. 19. International perspectives on aging (pp. 383–402). Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Rippon, I., Zaninotto, P., & Steptoe, A. (2015). Greater perceived age discrimination in England than the United States: Results from HRS and ELSA. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(6), 925–933. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbv040

Russel, D. (1996). UCLA loneliness scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40.

Savikko, N., Routasalo, P., Tilvis, R., Strandberg, T., & Pitkala, K. (2005). Predictors and subjective causes of loneliness in an aged population. Gerontology & Geriatrics, 41(3), 223–233.

Shankar, A., Hamer, M., McMunn, A., & Steptoe, A. (2013). Social isolation and loneliness: Relationships with cognitive function during 4 years of follow-up in the English longitudinal study of ageing. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75(2), 161–170.

Shiovitz-Ezra, S. (2013). Confidant networks and loneliness. In A. Borsch-Supan, M. Brandt, H. Litwin, & W. Guglielmo (Eds.), Active ageing and solidarity between generations in Europe: First results from SHARE after the economic crisis (pp. 349–358). Berlin: DeGruyter.

Shiovitz-Ezra, S., & Ayalon, L. (2010). Situational versus chronic loneliness as risk factors for all-cause mortality. International Psychogeriatrics, 22, 455–462.

Smart Richman, L., & Leary, M. R. (2009). Reactions to discrimination, stigmatization, ostracism, and other forms of interpersonal rejection: A multimotive model. Psychological Review, 116(2), 365–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015250

Sorkin, D., Rook, K. S., & Lu, J. L. (2002). Loneliness, lack of emotional support, lack of companionship, and the likelihood of having a heart condition in an elderly sample. Annual of Behavioral Medicine, 24(4), 290–298.

Storm, C., & Storm, T. (1987). A taxonomic study of the vocabulary of emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(4), 805.

Stravynski, A., & Boyer, R. (2001). Loneliness in relation to suicide ideation and parasuicide: A population –wide study. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 31(1), 32–40.

Sutin, A. R., Stephan, Y., Carretta, H., & Terracciano, A. (2015). Perceived discrimination and physical, cognitive, and emotional health in older adulthood. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(2), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2014.03.007

Suzman, R., & Beard, J. (2011). Global health and aging (pp. 1–32). US Department of State.

Swift, H. J., Abrams, D., Lamont, R. A., & Drury, L. (2017). The risks of ageism model: how ageism and negative attitudes toward age can be a barrier to active aging. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11(1), 195–231.

Theeke, L. A. (2007). Socidemographic and health-related risks for loneliness and outcome differences by loneliness status in a sample of older U.S. adults. Doctoral dissertation, Morgantown, West Virginia University.

Thorsen, S., Rugulies, R., Løngaard, K., Borg, V., Thielen, K., & Bjorner, J. B. (2012). The association between psychosocial work environment, attitudes towards older workers (ageism) and planned retirement. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 85(4), 437–445.

Thurston, R. C., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2009). Women, loneliness, and incident coronary heart disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(8), 836–842.

Tilvis, R. S., Kähönen-Väre, M. H., Jolkkonen, J., Valvanne, J., Pitkala, K. H., & Strandberg, T. E. (2004). Predictors of cognitive decline and mortality of aged people over a 10-year period. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 59(3), M268–M274.

van den Heuvel, W. J., & van Santvoort, M. M. (2011). Experienced discrimination amongst European old citizens. European Journal of Ageing, 8(4), 291–299.

Victor, C. R., Scambler, S. J., Bowling, A., & Bond, J. (2005). The prevalence of, and risk factors for, loneliness in later life: A survey of older people in Great Britain. Ageing and Society, 25, 357–375.

Vitman, A., Iecovich, E., & Alfasi, N. (2014). Ageism and social integration of older adults in their neighborhoods in Israel. The Gerontologist, 54(2), 177–189.

von Hippel, C., Kalokerinos, E. K., & Henry, J. D. (2013). Stereotype threat among older employees: Relationship with job attitudes and turnover intentions. Psychology and Aging, 28(1), 17–27.

Weiss, R. S. (1973). Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Weiss, R. S. (1987). Reflections on the present state of loneliness research. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 2(2), 1.

Wilson, R. S., Krueger, K. R., Arnold, S. E., Schneider, J. A., Kelly, J. F., Barnes, L. L., et al. (2007). Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(2), 234–240.

World Health Organization. (2007). Global age-friendly cities: A guide. Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. (2015). World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Zion Market Research. (2016, July). Global anti-aging market set for rapid growth to reach around USD 216.52 Billion in 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.zionmarketresearch.com/news/global-anti-aging-market

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

<SimplePara><Emphasis Type="Bold">Open Access</Emphasis> This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.</SimplePara> <SimplePara>The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.</SimplePara>

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Shiovitz-Ezra, S., Shemesh, J., McDonnell/Naughton, M. (2018). Pathways from Ageism to Loneliness. In: Ayalon, L., Tesch-Römer, C. (eds) Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism. International Perspectives on Aging, vol 19. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73820-8_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73820-8_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-73819-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-73820-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)