Abstract

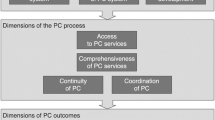

Integrated care (IC) suits patient needs better than fragmented health services. It is needed to organize care around the patient (Davis et al. 2005) and is seen as a critical factor in a high-performance healthcare system (McAllister et al. 2007). Care coordination is a process that addresses the health needs and wants of patients, including a range of medical and social support services (Rosenbach and Young 2000; Tarzian and Silverman 2002). Still there are problems in defining care coordination (Wise et al. 2007) which may be caused by the lack of knowledge about patient priorities. Hence patients must play a major role in designing the infrastructure and policies that will support the care coordination and integrated care approaches (Laine and Davidoff 1996).

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adams, K., & Corrigan, J. (2003). Priority areas for national action: Transforming health care quality. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, The National Academies Press.

Antonelli, R., McAllister, J., & Popp, J. (2009). Making care coordination a critical component of the pediatric health system: A multidisciplinary framework. New York: The Commonwealth Fund.

Ben-Akiva, M. E., & Lerman, S. R. (1985). Discrete choice analysis: Theory and application to travel demand. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bethge, S., Mühlbacher, A., & Amelung, V. (2015, November 7–11). The importance of the communicator for an integrated care program – A comparative preference analysis with Discrete Choice Experiments. International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) 18th Annual European Congress, Milan, Italy.

Bridges, J., Hauber, A., Marshall, D., Lloyd, A., Prosser, L., Regier, D., Johnson, F., & Mauskopf, J. A. (2011). Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: A Report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value in Health, 14(4), 403–413.

Bryan, S., & Parry, D. (2002). Structural reliability of conjoint measurement in health care: An empirical investigation. Applied Economics, 34(5), 561–568.

Bryan, S., Gold, L., Sheldon, R., & Buxton, M. (2000). Preference measurement using conjoint methods: An empirical investigation of reliability. Health Economics, 9(5), 385–395.

Campbell, S. M., Roland, M. O., & Buetow, S. A. (2000). Defining quality of care. Social Science and Medicine, 51(11), 1611–1625.

Chapple, A., Campbell, S., Rogers, A., & Roland, M. (2002). Users’ understanding of medical knowledge in general practice. Social Science and Medicine, 54(8), 1215–1224.

Cheraghi-Sohi, S., Hole, A. R., Mead, N., McDonald, R., Whalley, D., Bower, P., & Roland, M. (2008). What patients want from primary care consultations: A discrete choice experiment to identify patients’ priorities. Annals of Family Medicine, 6(2), 107–115.

Clark, M. D., Determann, D., Petrou, S., Moro, D., & de Bekker-Grob, E. W. (2014). Discrete choice experiments in health economics: A review of the literature. PharmacoEconomics, 32(9), 883–902.

Coulter, A. (2005). What do patients and the public want from primary care? BMJ, 331(7526), 1199–1201.

Criscione, T., Walsh, K. K., & Kastner, T. A. (1995). An evaluation of care coordination in controlling inpatient hospital utilization of people with developmental disabilities. Mental Retardation, 33(6), 364–373.

Danner, M., Hummel, J. M., Volz, F., Van Manen, J. G., Wiegard, B., Dintsios, C. M., Bastian, H., Gerber, A., & IJzerman, M. J. (2011). Integrating patients’ views into health technology assessment: Analytic hierarchy process (AHP) as a method to elicit patient preferences. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 27(04), 369–375.

Davis, K., Schoenbaum, S. C., & Audet, A. M. (2005). A 2020 vision of patient-centered primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(10), 953–957.

de Bekker Grob, E. W., Ryan, M., & Gerard, K. (2010). Discrete choice experiments in health economics: A review of the literature. Health Economics, 21(2), 145–172.

Ferrer, L. (2015). Engaging patients, carers and communities for the provision of coordinated/integrated health services. Working paper, WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen.

Fung, C. H., Elliott, M. N., Hays, R. D., Kahn, K. L., Kanouse, D. E., McGlynn, E. A., Spranca, M. D., & Shekelle, P. G. (2005). Patients’ preferences for technical versus interpersonal quality when selecting a primary care physician. Health Services Research, 40(4), 957–977.

Gerard, K., & Lattimer, V. (2005). Preferences of patients for emergency services available during usual GP surgery hours: A discrete choice experiment. Family Practice, 22(1), 28–36.

Hauber, A. B. (2009). Healthy-years equivalent: Wounded but not yet dead. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 9(3), 265–270.

Henke, K.-D., Mackenthun, B., & Schreyögg, J. (2002). Gesundheitsmarkt Berlin: Perspektiven für Wachstum und Beschäftigung. Baden-Baden: Nomos-Verl.-Ges.

Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Johnson, F. R., Hauber, A. B., & Özdemir, S. (2009). Using conjoint analysis to estimate healthy-year equivalents for acute conditions: An application to vasomotor symptoms. Value in Health, 12(1), 146–152.

Johnson, F. R., Lancsar, E., Marshall, D., Kilambi, V., Mühlbacher, A., Regier, D. A., Bresnahan, B. W., Kanninen, B., & Bridges, J. F. P. (2012). Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments. Report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Task Force.

Johnson, F. R., Ozdemir, S., Mansfield, C., Hass, S., Miller, D. W., Siegel, C. A., & Sands, B. E. (2007). Crohn’s disease patients’ risk-benefit preferences: Serious adverse event risks versus treatment efficacy. Gastroenterology, 133(3), 769–779.

Johnson, R. F., et al. (2015). Sample size and utility-difference precision in discrete-choice experiments: A meta-simulation approach. Journal of Choice Modelling, 16, 50–57.

Juhnke, C., & Mühlbacher, A. (2013). Patient-centredness in integrated healthcare delivery systems-needs, expectations and priorities for organised healthcare systems. International Journal of Integrated Care, 13, 1–14.

Kleinman, L., McIntosh, E., Ryan, M., Schmier, J., Crawley, J., Locke III, G. R., & De Lissovoy, G. (2002). Willingness to pay for complete symptom relief of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Archives of Internal Medicine, 162(12), 1361–1366.

Laine, C., & Davidoff, F. (1996). Patient-centered medicine. A professional evolution. JAMA, 275(2), 152–156.

Lancaster, K. J. (1966). A new approach to consumer theory. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill.

Lancaster, K. (1971). Consumer demand: A new approach. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lancsar, E., & Louviere, J. (2008). Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: A user’s guide. PharmacoEconomics, 26(8), 661–678.

Lancsar, E., Louviere, J., & Flynn, T. (2007). Several methods to investigate relative attribute impact in stated preference experiments. Social Science & Medicine, 64(8), 1738–1753.

Liptak, G. S., Burns, C. M., Davidson, P. W., & McAnarney, E. R. (1998). Effects of providing comprehensive ambulatory services to children with chronic conditions. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 152(10), 1003–1008.

Longo, M. F., Cohen, D. R., Hood, K., Edwards, A., Robling, M., Elwyn, G., & Russell, I. T. (2006). Involving patients in primary care consultations: Assessing preferences using discrete choice experiments. The British Journal of General Practice, 56(522), 35–42.

Markham, F. W., Diamond, J. J., & Hermansen, C. L. (1999). The use of conjoint analysis to study patient satisfaction. Evaluation & The Health Professions, 22(3), 371–378.

McAllister, J. W., Presler, E., & Cooley, W. C. (2007). Practice-based care coordination: A medical home essential. Pediatrics, 120(3), e723–e733.

McFadden, D. (1973). Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. Berkeley, CA: University of California.

Morgan, A., Shackley, P., Pickin, M., & Brazier, J. (2000). Quantifying patient preferences for out-of-hours primary care. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 5(4), 214–218.

Mühlbacher, A. C., & Bethge, S. (2014). Patients’ preferences: A discrete-choice experiment for treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. The European Journal of Health Economics, 6, 657–670.

Mühlbacher, A., & Bethge, S. (2015). Reduce mortality risk above all else: A discrete-choice experiment in acute coronary syndrome patients. PharmacoEconomics, 33(1), 71–81.

Mühlbacher, A., Bethge, S., & Eble, S. (2015a). Präferenzen für Versorgungsnetzwerke: Eigenschaften von integrierten Versorgungsprogrammen und deren Einfluss auf den Patientennutzen. Das Gesundheitswesen, 77(5), 340–350.

Mühlbacher, A. C., Bethge, S., Reed, S. D., & Schulman, K. A. (2015b). Patient preferences for features of health care delivery systems: A discrete-choice experiment. Health Services Research, 51, 704–727.

Mühlbacher, A., Bethge, S., & Tockhorn, A. (2013). Präferenzmessung im Gesundheitswesen: Grundlagen von Discrete-Choice-Experimenten. Gesundheitsökonomie & Qualitätsmanagement, 18(4), 159–172.

Mühlbacher, A., Bridges, J. F. P., Bethge, S., Dintsios, C. M., Schwalm, A., Gerber-Grote, A., & Nübling, M. (2016). Preferences for antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis C: A discrete choice experiment. European Journal of Health Economics.

Mühlbacher, A. C., Junker, U., Juhnke, C., Stemmler, E., Kohlmann, T., Leverkus, F., & Nubling, M. (2014). Chronic pain patients’ treatment preferences: a discrete-choice experiment. Eur J Health Econ, 16, 613–628.

Mühlbacher, A., Lincke, H., & Nübling, M. (2008). Evaluating patients’ preferences for multiple myeloma therapy, a discrete choice experiment. GMS Psycho-Social-Medicine, 5, PMC2736517.

Mühlbacher, A., Nübling, M., Rudolph, I., & Linke, H. J. (2009). Analysis of patient preferences in the drug treatment of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A discrete choice experiment. BMC Health Services Research.

Mulley, A., Trimble, C., & Elwyn, G. (2012). Patients’ preferences matter – Stop the silent misdiagnosis. London: The King’s Fund.

National Quality Forum. (2006, August). National Quality Forum.

Ostermann, J., Njau, B., Mtuy, T., Brown, D. S., Muhlbacher, A., & Thielman, N. (2015). One size does not fit all: HIV testing preferences differ among high-risk groups in Northern Tanzania. AIDS Care, 27, 595–603.

Peek, C. J. (2009). Integrating care for persons, not only diseases. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 16(1), 13–20.

Porter, M. E., & Teisberg, E. O. (2006). Redefining health care: Creating value-based competition on results. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Rao, M., Clarke, A., Sanderson, C., & Hammersley, R. (2006). Patients’ own assessments of quality of primary care compared with objective records based measures of technical quality of care: Cross sectional study. BMJ, 333(7557), 19.

Rodriguez, H., von Glahn, T., Rogers, W., & Gelb Safran, D. (2009). Organizational and market influences on physician performance on patient experience measures. Health Services Research, 44, 880–901.

Rosenbach, M., & Young, C. (2000). Care coordination and medicaid managed care: Emerging issues for states and managed care organizations. Spectrum, 73(4), 1–5.

Ryan, M., & Farrar, S. (2000). Using conjoint analysis to elicit preferences for health care. BMJ, 320(7248), 1530–1533.

Ryan, M., & Gerard, K. (2003). Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: Current practice and future research reflections. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 2(1), 55–64.

Ryan, M., & Hughes, J. (1997). Using conjoint analysis to assess women’s preferences for miscarriage management. Health Economics, 6(3), 261–273.

Ryan, M., Gerard, K., & Amaya-Amaya, M. (2008). Using discrete choice experiments to value health and health care. Dordrecht: Springer.

Ryan, M., Bate, A., Eastmond, C. J., & Ludbrook, A. (2001a). Use of discrete choice experiments to elicit preferences. Quality in Health Care, 10(Suppl 1), i55–i60.

Ryan, M., Scott, D. A., Reeves, C., Bate, A., van Teijlingen, E. R., Russell, E. M., Napper, M., & Robb, C. M. (2001b). Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: A systematic review of techniques. Health Technology Assessment, 5(5), 1–186.

Scott, A., & Vick, S. (1999). Patients, doctors and contracts: an application of principal-agent theory to the doctor-patient relationship. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 46(2), 111–134.

Scott, A., Watson, M. S., & Ross, S. (2003). Eliciting preferences of the community for out of hours care provided by general practitioners: A stated preference discrete choice experiment. Social Science and Medicine, 56(4), 803–814.

Sevin, C., Moore, G., Shepherd, J., Jacobs, T., & Hupke, C. (2009). Transforming care teams to provide the best possible patient-centered, collaborative care. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 32(1), 24–31.

Tarzian, A. J., & Silverman, H. J. (2002). Care coordination and utilization review: Clinical case managers’ perceptions of dual role obligations. The Journal of Clinical Ethics, 13(3), 216–229.

Telser, H., Becker, K., & Zweifel, P. (2008). Validity and reliability of willingness-to-pay estimates: Evidence from two overlapping discrete-choice-experiments. The Patient, Patient-Centered Outcome Research, 1, 283–293.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2014). The patient preference initiative: Incorporating patient preference information into the medical device regulatory processes. Public Workshop, September 18–19, 2013. FDA White Oak Campus, Silver Spring, MD.

Ubach, C., Scott, A., French, F., Awramenko, M., & Needham, G. (2003). What do hospital consultants value about their jobs? A discrete choice experiment. BMJ, 326(7404), 1432.

Vick, S., & Scott, A. (1998). Agency in health care. Examining patients’ preferences for attributes of the doctor-patient relationship. Journal of Health Economics, 17(5), 587–605.

Wensing, M., Jung, H. P., Mainz, J., Olesen, F., & Grol, R. (1998). A systematic review of the literature on patient priorities for general practice care. Part 1: Description of the research domain. Social Science and Medicine, 47(10), 1573–1588.

Wise, P., Huffman, L., & Brat, G. (2007). A critical analysis of care coordination strategies for children with special health care needs. Technical Review No. 14. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ Publication No. 07-0054.

Wismar, M., & Busse, R. (2002). Outcome-related health targets-political strategies for better health outcomes – A conceptual and comparative study (part 2). Health Policy, 59(3), 223–242.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2015). WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services. Interim report. WHO reference number: WHO/HIS/SDS/2015.6.

Acknowledgements

Within the US study, the SSRI at DUKE University and DUKE Health View supported the recruitment of patient for the patient preference study. The study was financially supported by the Commonwealth Fund and the Harkness Fellowship in Healthcare Policy and Practice, New York, USA granted to Axel Mühlbacher. Susanne Bethge received a stipend from the International Academy of Life Science, Hannover, Germany. The German study was financially supported by Berlin Chemie AG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Mühlbacher, A., Bethge, S. (2017). Patients Preferences. In: Amelung, V., Stein, V., Goodwin, N., Balicer, R., Nolte, E., Suter, E. (eds) Handbook Integrated Care. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56103-5_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56103-5_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-56101-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-56103-5

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)