Abstract

This paper uses cohort fertility tables and periodic surveys to provide an overview of the development of childlessness in the United States. Estimates of the temporarily, involuntarily, and voluntarily childless are available. Childlessness has attracted considerable attention because it doubled between the mid-1970s and the mid-2000s, from 10 to about 20 %. The U.S. has experienced considerable variation in levels of childlessness. The challenging living conditions during the Great Depression of the 1930s were the principal cause of high childlessness. The contrasting favorable living standards and enlightened public policies of the late 1940–1960s were instrumental in maintaining low childlessness. For much of the twentieth century, childlessness was higher among blacks than among whites mainly because their living conditions were more difficult. Subsequently, black childlessness declined below that of whites possibly due to rapid improvements in health and living conditions which nonetheless remained inferior. Numerous additional factors have been shaping childlessness in the U.S., including high female employment rates, the conflict between work and family responsibilities, separation of spouses due to wars or incarceration, high costs of childrearing, inadequate childcare infrastructure, insecurity of employment and income, uncertainty of spousal relationships, and concern for the wellbeing of children. Because the interactions of factors which shape childlessness are not well understood, it is difficult to make predictions. Future trends will depend on the extent to which material conditions will facilitate or obstruct family formation, and cultural norms and personal attitudes change.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

In recent decades, childlessness among women in the United States has attracted a considerable amount of attention in the professional literature, and is frequently discussed in newspapers and on radio and television talk shows. This does not come as a surprise, as the percentage of women who do not have any children by the end of their reproductive years doubled between the mid-1970s and the mid-2000s, from about 10 to 20 %. Since then, however, the share of women who remain childless has been declining: in 2010–2012, the share was around 15 % (Table 8.1).Footnote 1 While establishing the levels of and the trends in childlessness is relatively simple, determining the circumstances and reasons which lead women and couples to remain childless is more complex.

Three different sources of statistical data on childlessness are available in the U.S. This wealth of data is almost as much a curse as it is a blessing. However, using data from all three sources one can obtain a good approximate idea of the levels of and the trends in childlessness. Yet because each source provides somewhat different data, it is difficult to determine which one most closely reflects reality. On balance the positive aspect of good approximate information prevails. Moreover, the overall perception provided by the three sources of data is consistent. Not only that. The available sources offer various types of information, including some kinds which are relatively rare. One of the sources contains a time series spanning an entire century, which is also broken down by race. Another source provides data not only by race, but also for Hispanics. A third source contains data on whether women are temporarily, voluntarily, or non-voluntarily childless, as well as information about women’s personal characteristics and selected attitudes to work and family. These data are available for a span of close to four decades. Knowledge which can be gleaned from all three sources of data is likely to be expanded in the future.

Following this introduction, the sources of data are discussed. In Sect. 8.3 levels of and trends in childlessness are outlined. Section 8.4 deals with motivations and reasons for childlessness. Section 8.5 discusses trends and circumstances of black childlessness. The chapter concludes with an epilogue.

2 Sources of Data

The three sources of statistical data on childlessness are cohort fertility tables (National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), the biannual supplements on fertility of the Current Population Survey (Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics), and the National Survey of Family Growth (National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [NCHS]).

2.1 The Cohort Fertility Tables

The Cohort Fertility Tables consist of two sets. The first set is based on recorded period fertility data for the years 1917–1973, and was prepared by Robert L. Heuser (1976). It provides information on childbearing of complete and incomplete birth cohorts of 1868–1959. The second set uses period data for 1960–2005, and was prepared by Brady E. Hamilton in collaboration with Candace M. Cosgrove (2010). Hamilton and Cosgrove updated this set with period fertility data for 2006–2009. It provides information on childbearing of complete and incomplete birth cohorts of 1911–1995. The Heuser tables can be linked with the Hamilton and Cosgrove tables to create a series of data on childlessness for 93 consecutive birth cohorts.

2.2 The Fertility Supplement of the Current Population Survey

The Fertility Supplement of the Current Population Survey is one of 20 supplements sometimes included in the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly survey of households conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau for the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The CPS collects and maintains a comprehensive body of labor force data, including information on employment, unemployment, hours of work, earnings, and other demographic and labor force characteristics. The periodic fertility supplement provides data on the number of children women aged 15–50 have ever had, and their characteristics. It is usually conducted every 2 years, but the intervals have varied from 1 to 4 years (see Table 8.1 and Fig. 8.3). Since the mid-1990s data on the U.S. Hispanic populationFootnote 2 have been provided (Bachu 1995).

2.3 The National Survey of Family Growth

The National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) gathers information on family life, marriage and divorce, pregnancy, infertility, use of contraception, and men’s and women’s health; i.e. data on fertility and on the intermediate factors that explain fertility. The NSFG was conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) in 1973, 1976, 1982, 1988, 1995, and 2002. The most recent NSFG covered the years 2006–2010 (Martinez et al. 2012). In these surveys childless women are comprised of three categories defined as follows (Abma and Martinez 2006; Martinez et al. 2012):

Temporarily Childless

women are those who have not had any live births and expect a birth in the future.

Involuntarily Childless

women are those with a fecundity impairment who reported to be sterile for non-contraceptive reasons; subfecund, i.e. they reported difficulty conceiving or delivering a baby or difficulty for partner to father a baby; or a doctor advised the woman never to become pregnant because of a medical danger to her, her fetus or both; married or cohabiting women that have had a 3 year period of unprotected sexual intercourse with no pregnancy.

Voluntarily Childless

women are those who do not expect to have any children, and are either fecund or surgically sterile for contraceptive reasons.

Note that the cohort fertility tables are based on data from administrative birth records, whereas the other two data sources are based on sample surveys. The sample surveys provide information on the characteristics of mothers and their children which are not available in birth records. However, the estimates of common measures based on the sample surveys are not precisely the same as those based on administrative birth records.

3 Levels of and Trends in Childlessness

3.1 Cohort Fertility Tables

In any given birth cohort, the youngest women bear few children. With each passing year, these women will have borne more children, and the share of women who remain childless declines. To ensure the comparability of the rates of childlessness between cohorts, the data on the proportion of childless women at the end of their childbearing years are assembled for each cohort. Figure 8.1 depicts the shares of all U.S. childless women, and of white and black women at age 50 in the Heuser (1976) and in the Hamilton and Cosgrove (2010) cohort fertility tables.

Among the 40 cohorts born between the late 1860s and the early 1910s, around 20 % of white women remained childless. Women who lived through the main years of their childbearing period during the core years of the historic economic depression of the 1930s—cohorts born between 1906 and 1911—experienced relatively high rates of childlessness, about 21 %. However, this was not dramatically more than most of the preceding 40 cohorts. A rapid decline in the share of childless women started with the 1913 birth cohort and lasted through the 1925 cohort that reached a childless rate of 9 %. A low share of childlessness among white women fluctuating between 8 and 10 % was retained for almost 20 cohorts from the 1925 through the 1943 birth cohort. A pronounced increase in the shares of childless women ensued, from 10 % among the 1943 cohort to 18 % among the 1953 cohort. The childless rate at age 50 was close to 18 % for a few cohorts and then started to decline to around 17 % in the 1959 and 1960 cohorts (Fig. 8.1).

The long-term trends in the shares of childless black women differed from those of white women. For about 60 cohorts, starting with those of the mid-1880s through those of the mid-1940s, black women experienced higher rates of childlessness than white women. Notably, almost one-third of black women who were in their most fertile years during the Great Depression of the 1930s remained childless. With a time lag of about five cohorts shares of childless black women declined from 29 % among women born in 1916 for more than 30 cohorts to a low of 6 % in the 1948 birth cohort. Thereafter, the share of childless black women increased reaching a share of 11 % in the 1960 cohort (Fig. 8.1).

Although numbers of births after age 40 have increased in recent years (Sobotka 2009), these still tend to be relatively small. Consequently, trends in the shares of childless women at age 40 are essentially the same as trends in the shares of childless women at age 50 (Fig. 8.2). Thus the delineation of trends can be extended for 10 additional cohorts, namely for U.S. women trends of childless women can be obtained by observing trends of shares at age 40 for the 1960s birth cohorts. These women concluded their childbearing during the 2010s, and their principal period of childbearing was during the mid- to late 1980s and early 1990s.

Among white women the declining trend of childless women extended into the 1960s cohorts. The share of childless women in the 1960 birth cohort at age 40 was 17.7 % and declined to 14.6 % in the 1970 birth cohort (Fig. 8.2). This implies that around 13 % of white women in the 1970 cohort will be childless at age 50. The rising trend in childlessness among black women of the 1950s cohorts stalled among the 1960s cohorts. The share of women who were childless at age 40 was 11.9 % among the 1960 birth cohort, and 12.1 % among the 1970 birth cohort (Fig. 8.2). This implies that around 11 % of black women in the 1970 cohort will be childless.

It appears that shares of white and black childless women in the 1970 cohort will be quite similar. The difference in the shares of white and black childless women in the 1950 cohort at age 40 was 10.2 percentage points which declined to 5.8 points in the 1960 cohort and to 2.5 points in the 1970 birth cohort.

Levels and trends of overall shares of childless women follow the levels and trends of white women quite closely. This is not surprising, as the majority of the U.S. population was and still is white, although the percentage of whites has been declining. In 1900 about 88 % of the U.S. population was white and 12 % was black (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1975). These percentages were essentially maintained through 1970. As of 2000, whites comprised about 82 % and blacks 13 % of the population (U.S. Census Bureau 2012). The effect of black childlessness on the overall levels and trends is nonetheless discernable. When black childlessness is high the overall curve is above the white one, and vice versa.

The share of all childless women at age 50 in the 1960 cohort was 15.5 % and at age 40–16.5 %, a difference of exactly 1.0 percentage point. The share of all childless women at age 40 in the 1970 cohort was 13.8 %. Thus it is virtually assured that the overall share of childless women in the 1970 cohort at age 50 will be below 13 %, because the difference in the 10 years younger cohort was 1.0 percentage point and this difference of childlessness between ages 40 and 50 in a particular birth cohort was growing.

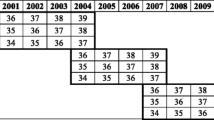

3.2 Fertility Supplements of the Current Population Survey

In the fertility supplements of the Current Population Surveys parity distributions—and thus also the shares of childless women—are provided for 5-year age groups. Until recently the oldest age group for whom these data were available was 40–44. Since 2012 the age group 45–50 has been added. Table 8.1 and Fig. 8.3 are based on data for the 40–44 age group. Although childbearing does not end at age 44, this cut off was necessary to obtain long-term time series.

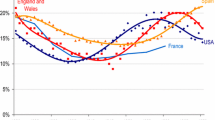

According to these data the average share of all childless women aged 40–44 in the United States increased from 10 % around 1980 to almost 20 % in the 2000s, i.e. the proportion of childless women increased almost twofold within 20 years. Toward the end of the 2000s and the early 2010s, childlessness declined (Table 8.1). In the mid-1990s the shares of white childless women were almost 10 % higher than those of black women. By 2008–2012 the differences between white and black women in the rates of childlessness had diminished (Fig. 8.3 and Table 8.1).

When comparing childlessness of Hispanic women with childlessness among white and black women one has to keep in mind that in U.S. statistics Hispanics are included in the categories of “white” and “black.” Hispanics are considered an ethnic minority, not a race. It is nonetheless possible to get an idea of the effect of Hispanic childlessness on overall levels of childlessness of the race categories. Even though the Hispanic childlessness rate (5th numerical column in Table 8.1) is on average about 30 % lower than childlessness of non-Hispanic white women (3rd col.), the difference between the shares of all white childless women (2nd col. which includes white Hispanic women) and non-Hispanic white women is relatively small, on average this difference is only 0.9 percentage points (last col. in Table 8.1). The reason for such a small difference is that in 2010, for instance, Hispanic women constituted only about 18 % of white women, although the share of Hispanics in the population was increasing (U.S. Census Bureau 2011: Table 6). The effect of Hispanic black childlessness on total black childlessness was even smaller as the proportion of Hispanics among blacks was only about 5 % in 2010.

3.3 The National Surveys of Family Growth (NSFG)

Shares of childless women ages 40–44 rose from 7 % in the 1973–1976 rounds to 18 % in the 1995 round of the NSFG. In the rounds conducted during the 2000s, the shares of childless women had settled at 15 % (Table 8.2 and Fig. 8.4). Among childless women ages 40–44 the smallest shares were experienced by the temporarily childless. If the measurements had been taken at the end of women’s reproductive period, as was done in the cohort fertility tables, there would not be any temporarily childless women. As women ages 40–44 is the oldest category that can be analyzed, the temporarily childless women have a significant impact on the overall trends in childlessness. Since women are postponing births to higher ages, a larger amount of births are borne by older women; thus, an increasing proportion of women in the 40–44 age group still expect to bear children. While the share of temporarily childless older women has been increasing steadily, it still represents only 3 % of all women and around one-fifth of all childless women. The share of all women who are involuntarily childless has been relatively stable at an average of 5 %. In the 1973–1976 rounds, the share of involuntarily childless women as a proportion of all childless women was 60 % because the overall numbers of childless women were relatively small. In the latest rounds, about one-third of childless women would probably want to have children, but for one reason or another—primarily related to a health issue—they have been unable to achieve this goal.

The NSFG definitions used to distinguish between voluntary and involuntary childlessness appear to be straightforward and clear (see Sect. 8.2.3 above). However, scholars have pointed out that an unknown segment of the women who at the end of their reproductive period report being voluntarily childless or having become involuntarily childless were postponing childbearing for various reasons until it became too late for them to bear children (Rindfuss et al. 1988: throughout). In other words, some, possibly many, women wind up being unintentionally childless as a result of having postponed childbearing. Regardless of how the childlessness occurred, using NSFG definitions, the percentage of the voluntarily childless increased from one-third in the 1970s rounds to approximately one-half of childless women in subsequent rounds (Table 8.2).

3.4 Personal Characteristics and Attitudes of Childless Women

There is ample evidence from several rounds of the NSFG that childless women, and particularly the voluntarily childless, are disproportionately white, are employed full-time, and have a higher education; and are less likely to be currently or formerly married and are less religious (Abma and Martinez 2006). For example, data from the 2002 round show that among women aged 35–44, 69 % of the voluntarily childless had some college or higher education, compared to 17 % among all women of that age; 76 % of the voluntarily childless were working full-time, compared to 51 % among all women; 79 % were non-Hispanic white, compared to 71 % among all women; and 35 % never attended religious services, compared to 17 % among all women (Abma and Martinez 2006).

Among the women aged 35–44, the voluntarily childless also differed from the temporarily and involuntarily childless in terms of economic characteristics. They had the highest individual and family incomes, the most extensive past work experience, and were the most likely to be employed in professional and managerial occupations. For example, according to the results of the 1995 round, 57 % of the voluntarily childless had individual annual earnings of over US$25,000, compared to 41 % of the temporarily childless and 36 % of the involuntarily childless; and 84 % had worked more than 15 years, compared with 72 % of the temporarily childless and 77 % of the involuntarily childless (Abma and Martinez 2006).

On the whole, the voluntarily childless tend to differ from women who have children and from the temporarily or the involuntarily childless in terms of their attitudes regarding gender egalitarianism, work, and family. For example, in their responses to questions in the 1995 round, 82 % of voluntarily childless versus 72 % of women with children disagreed with the statement “a man can make long-range plans, a woman cannot;” and 84 % of the voluntarily childless versus 75 % of the women with children agreed with the statement “young girls are entitled to as much independence as boys.” The voluntarily childless also stood out in their response to the question of whether “women are happier if they stay at home and take care of their children;” 87 % of them disagreed, compared with around 76 % of the women who had children or were temporarily or involuntarily childless (Abma and Martinez 2006).

4 Reasons and Motivations for Remaining Childless

In a discussion of the biological factors which contribute to childbearing motivations, Foster (2000: 227) argued that because of their genetic predisposition to nurture and the effects of hormones, “most women, motivated by a genetically developed desire to nurture, will choose to have at least one child, given reasonably favorable circumstances.” Moreover, McQuillan et al. (2008: 17) established that motherhood is valued by mothers and non-mothers alike, and that “there is no evidence that valuing motherhood is in conflict with valuing work success among non-mothers, and among mothers the association is positive.” Yet for prolonged periods a fifth of U.S. women, i.e. around 20 %, remained childless. Why?

In the first place about 5 % of women cannot or should not bear children; they are involuntarily childless, mostly due to fecundity impairments or health issues (Fig. 8.4 and Table 8.2). Then there are the temporarily childless, i.e. those that are still expecting to have a child. However, these women can no longer be considered temporarily childless once they have reached the end of their childbearing period. The remainder of women remains childless for a wide variety of reasons.

People grow up and live in differing social, cultural, and economic circumstances which influence their decisions regarding childbearing. They live aided or obstructed by a material world, and are affected by an array of social norms. They may also have their own independent reasons for not having children. Both the material conditions and the norms affecting their decisions may change over time. If we were to accept the notion that every woman has a natural desire to have children, irrespective of her surroundings, there would not be any voluntary childlessness. Indeed, there was a time in U.S. history when only around 8 % of white women and only about 5 to 6 % of black women were childless. Among these women, the rates of voluntary childlessness must have been negligible. The 1973–1976 round of the NSFG found that only 2 % of women reported being voluntarily childless, which implies that this share might have been even lower during the 1960s among white women. Moreover, the 5–6 % rate of childlessness among black women leaves very little room for voluntary childlessness. On the other hand, as was pointed out above, at certain points in time around 20 % of white women and almost 30 % of black women were childless, which implies that the shares of “voluntary” childlessness were large.

The basic explanation for these extreme high and low childlessness rates is the fact that the former occurred at a time of economic hardship and psychological stress for large strata of the population affecting family life during the Great Depression which started in 1929 and lasted through the early to mid-1930s. Conversely, the low childlessness rates occurred when a majority of the population experienced favorable economic and social conditions for childbearing after the Second World War. In his recently published book, Labor’s Love lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working-Class Family in America, Cherlin (2014) masterfully describes in great detail changes in American family life over the past two centuries. He characterizes “the Great Depression [as] a cataclysmic event in the United States in its depth and duration” (Cherlin 2014: 60). Based on contemporary sociological research of Komarovsky (1940), Cherlin discusses the effect of the Depression, inter alia, on reproductive behavior.

Their sex lives often deteriorated: in twenty-two out of thirty-eight families for which adequate information was collected, the frequency of sexual relations declined--including four families in which sex stopped altogether. In some cases, however, couples reduced sexual activity not because of emotional strain but in order to lower the chance that the wife would become pregnant. Without modern means of birth control such as the pill or the IUD, financially struggling couples did what they could to avoid having another mouth to feed. One parent said, “It is a crime for children to be born when the parents haven’t got enough money to have them properly” (Cherlin 2014: 79).

The low shares of childlessness make clear sense in light of Cherlin’s characterization of the living conditions of American families in the post-World War II years.

Why did young couples have so many children? One reason lay in the unique life histories of the generation who were in their twenties and thirties. They experienced the Great Depression as children or adolescents and then a world war erupted as they reached adulthood. After enduring these two cataclysmic events, the “great generation,” as they are sometimes called, was pleased in peacetime to turn inward toward home and family. … Family life was the domain in which they found … security. Raising children provided a sense of purpose to adults who had seen how fragile the social world could be. … Moreover, conditions were favorable for family formation and fertility: unemployment rates were low, wages were rising, and the government had enacted the GI Bill, which offered low-interest home mortgage loans to veterans so that they could buy single-family homes. … Employers in the rapidly expanding American economy were forced to offer higher wages in order to attract new workers because they were in short supply (Cherlin 2014:115).

What remains to be clarified are the social, cultural, and economic circumstances shaping childlessness levels and trends prior to the Great Depression of the 1930s and the levels and trends unfolding during the two to three last decades of the twentieth century, as well as the peak and subsequent decline in childlessness in the early twenty-first century.

It could be considered odd that for 40 years (or 40 birth cohorts, i.e. 1867–1907) childlessness was at a similar level as during the Great Depression (Fig. 8.1). Morgan (1991) has argued that the period of high childlessness in late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was mainly due to a strong motivation to delay marriage and childbearing, which eventually resulted in many women remaining childless, even though that was not their initial intention. Childbearing delays were significantly more pronounced in the economically more advanced states of the northeast. Many young women working in mills “may have been important income earners. Pressure for them to marry may have been replaced by pressure to continue supporting the family” (Morgan 1991: 801). Furthermore, the harsh conditions of the economic depression of the 1890s might have had an impact similar to that of the Great Depression of the 1930s, even though it was not as long or as deep. In addition, the risk of remaining childless would have been greater when childbearing was delayed, as sub-fecundity and sterility increases among women in their thirties. Finally, growing numbers of women were entering professions during this period, and these women tended not to marry; or, if they married, they often remained childless.

Turning our attention to the end of the twentieth century and the early twenty-first century, numerous societal developments have been taking place simultaneously, each of which has played a role in shaping contemporary childbearing behavior, and has thus contributed to trends in childlessness. These include:

-

The re-emergence of marriage and childbearing postponement (Kohler et al. 2002; Hašková 2007; Goldstein et al. 2009; Frejka 2011)

-

Rising female labor force participation rates, which are now almost as high as those of men (Oppenheimer 1994; Bianchi 2011)

-

The work-family dilemma for employed women (Bianchi 2011)

-

The status of the childcare infrastructure (Laughlin 2013)

-

The increase in women’s earnings, and the growth in their income relative to that of men (Cherlin 2014: 126; Wang et al. 2013)

-

The growing empowerment of women (Anonymous 2009)

-

High rates of incarceration (Tsai and Scommenga 2012)

-

The deployment of men and women in wars (Adams 2013)

-

Technological developments in production and communication, and their impact on the composition of the work force (Karoly and Panis 2004; Economist Intelligence Unit 2014)

-

The hollowing out of the work force (Cherlin 2014: 124–125)

-

Changes in the class structure of society, with education playing the decisive role (Cherlin 2014)

-

Growing job insecurity, particularly among the less educated (Farber 2010)

-

Changing marriage and cohabitation patterns (Cherlin 2009)

-

Changing income and wealth distribution patterns (Saez and Zucman 2014)

-

Income stagnation among a large share of the population (Krugman 2007; Fry and Kochhar 2014)

The above developments may influence women and their partners—in various ways, at different stages, and to differing degrees—in their inadvertent or conscious deliberations about whether to remain childless.

On the other hand there are those, including professionals such as psychologists and physicians, who have argued that some women and men decide to remain childless for their own subjective reasons. These individuals presumably engage in an independent decision-making process in which they focus on their personal motivations and preferences, rather than allowing themselves to be influenced by their circumstances. Scott (2009: 75–110; 222) reported the results of a survey of childless individuals which found that the six most compelling motivation statements for not having children were:

-

I love our life, our relationship, as it is, and having a child won't enhance it.

-

I value freedom and independence.

-

I do not want to take on the responsibility of raising a child.

-

I have no desire to have a child, no maternal/paternal instinct.

-

I want to accomplish/experience things in life that would be difficult to do if I was a parent.

-

I want to focus my time and energy on my own interests, needs, or goals.

Taking into account the wide range of circumstances and personal subjective reasons which can affect people’s decisions about whether to have children can help us to better understand the increase in the share of women who remained childless which occurred during the final decades of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century. However, the reasons for the apparent reversal in this trend in the early years of the twenty-first century have yet to be explored. That is a topic for discussion and research in the near future, especially if this trend continues.

5 Black Childlessness: Trends and Explanations

For almost 60 birth cohorts (1883–1942) childlessness was higher among black than among white women (Fig. 8.1). At its peak black childlessness was 2.4 times higher than it was among white women – in the 1924 and 1925 birth cohorts. Starting with the cohorts born in the early 1940s, this trend was reversed, and black women became less likely than white women to be childless. Among the youngest cohorts, those born in the late 1950s and the 1960s, the shares of black and of white Americans who are childless are converging at around 12–15 % (Figs. 8.1 and 8.2). The relatively low childlessness among black women and the convergence with white childlessness since the end of the twentieth century is generally confirmed by data from the Fertility Supplements of the Current Population Survey as well as the National Surveys of Family Growth.

The basic reasons for high black childlessness were analogous to those shaping white childlessness, namely difficult economic and social settings, psychological stress and social norms. In addition, living conditions of black Americans were incomparably more difficult than those of whites. Racial segregation, discrimination, and inequalities have been basic features of American society throughout its history (Massey 2011), and are reflected in virtually all aspects of life, such as economic opportunities, remuneration, schooling, housing, and access to health and reproductive services.

Farley (1970: 217–226) was the first to analyze deteriorating health conditions of blacks systematically, and their effect on reproductive behavior during the first three decades of the twentieth century. An increase in the prevalence of venereal diseases, such as syphilis and gonorrhea may have been an important factor generating the fertility decline and the increase in childlessness among blacks, which culminated in the 1930s. Farley was criticized by McFalls (1973: 18) and others who argued in favor of “a more conservative interpretation of the importance of VD in the natality history of the black population.” Yet McFalls (1973: 18) conceded that “health factors undoubtedly played a more significant role” than other societal factors.

But what explains the decline in black childlessness and the crossover from relatively high to relatively low levels of childlessness from the 1941 to the 1942 birth cohorts? The decline in the childlessness rate of black women started with the cohorts most affected by the Great Depression, namely those born around 1915, and lasted until the 1948 cohort, from a share of 30 % to 6 % (Figs. 8.1 and 8.2). The childlessness decline among blacks took more than twice as long as that for white women, 33 compared to 14 cohorts. The childlessness descent for white women also started with the cohorts most affected by the depression of the 1930s, but stopped when living conditions started to improve significantly after the Second World War and essentially settled at that level for over 20 birth cohorts. Among black women childlessness stopped declining temporarily for a few birth cohorts – those born between 1926 and 1931 – but then resumed its decline with new force. Black childlessness declined from 20 % in the 1931 cohort to 6 % in the 1948 cohort.

The passage of the Social Security Act in 1935 strengthened government support for health activities (Farley 1970: 230–235). Title VI of that act appropriated money “for the purpose of assisting States, counties…. in establishing and maintaining adequate public health service, including the training of personnel for State and local health work…” This was an important element in the development of the health system. The resulting improvements in the health of the black population in turn led to declines in childlessness.

Moreover, there may be some justification to assume that improvements in living conditions and educational attainment levels among the black population during the second half of the twentieth century were associated with the long-term decline in childlessness. This progress was both absolute as well as relative to that of the white population. While living conditions for blacks remained inferior to those of whites, the disparities were narrowing as blacks were catching up. On average, incomes of blacks were rising faster than those of whites, especially during the 1990s (Fig. 8.5). Rates of poverty among blacks were also improving. Based on the definition of poverty of the U.S. Census Bureau, the ratio of blacks to whites who were living in poverty declined from 3.4 in 1970 to 2.1 in 2010 (DeNavas-Walt et al. 2012: Table B-1). In addition, educational attainment levels of blacks were increasing faster than those of whites. Between 1960 and 2009, the shares of blacks aged 25 and older who had graduated from high school rose from 20.1 to 84.1 %, whereas the corresponding shares of whites increased from 43.2 to 87.1 % (U.S. Census Bureau 2012: Table 225). Over the same period, the shares of blacks aged 25 and older who had graduated from college grew from 3.1 to 19.3 %, while the corresponding shares of whites increased from 8.1 to 29.9 % (U.S. Census Bureau 2012: Table 225).

Households by total money income (in 1000 of constant 2008 U.S. dollars) and race of householder, black as percent of white income, 1967–2010 (Source: DeNavas-Walt et al. (2012), Table A-2)

What might be the reasons for the most recent turnaround – the doubling in black childlessness from 6 % in the 1948 birth cohort to 12 % in the 1968 cohort? The numerous societal developments shaping childlessness that have been taking place around the turn of the century listed above, together with the subjective motivations of women for not having children, surely played a role in influencing contemporary childbearing behavior and thus contributed to the increase in childlessness of black women.

Other important factors which might have influenced the recent rise in black childlessness are changes in union formation and marital trends, and in fertility trends within unions. According to Cherlin (2009: 169), “the larger story for African Americans is a sharp decline in marriage that is far greater than among other groups.” In 2010 the share of black married women over age 18 was a mere 31 % compared to 61 % in 1960. In contrast, among white women this share declined from 74 to 55 % (Cohn et al. 2011). These developments are in line with the findings of Espenshade (1985: 209), who concluded that “at least since 1960 in the United States, a weakening of marriage has been under way. The fading centrality of marriage in the lives of American men and women is more noticeable for blacks than for whites.” Only 24 % of black women aged 15–44 were married compared with 46 % of white non-Hispanic women according to the NSFG 2006–2010 round (Copen et al 2012: 12).

A comprehensive, albeit complex, set of explanations for declining marriage rates among blacks has been revealed by research conducted by Banks (2011). Most black women want to marry and have children, as getting married is seen as a marker of status and social prestige, and remains an aspiration. Almost all black women would prefer to have a partner of the same race, as they are acculturated to date and marry black men, and rarely marry across racial lines. In the African American community, however, there is a considerable shortage of successful black men who are educated, employed, and have respectful earnings. One reason for this shortfall is the extraordinarily high rate of incarceration of black men (Massey 2011:10; Tsai and Scommenga 2012). Second, black men are up to three times more likely than black women to marry a person of a different race. Third, at all educational levels men’s attendance and attainment rates are far below those of women. In these circumstances, many black women remain single or marry less educated black men. In such unions, women tend to be better educated and earn more money than their spouse, which can result in tensions over gender roles. Such marriages have a high potential to dissolve. Hence a high divorce rate among blacks is another reason why their marriage rates are low.

Data on trends in the types of first unions for women aged 15–44 confirm the decline in percentages of women who are married. Shares of marriages in first unions declined from 25.2 % in 1995 to 12.5 % in the 2006–2010 round of the National Survey of Family Growth (Table 8.3). Over the same period, the share of unions which were cohabitations increased from 35.4 to 49.2 %. Consequently, the percentages of black women of reproductive age who were not in any union hardly changed between the 1995 and the 2006–2010 NSFG rounds, i.e. instead of getting married a large share of black women were living in a consensual union. That implies that the recent increase in childlessness of black women does not appear to be associated with a decline in the percentage of women who are in a union. The combined shares of cohabiting and married women were 60.6 and 61.7 % in 1995 and 2006–2010, respectively.

What did change dramatically between 1995 and 2013 was the fertility rate of unmarried black women; it declined by 17 %, from 74.5 to 61.7 births per 1000 unmarried black women (Table 8.4). It was this significant decline in the fertility rate which was associated with the rise in black childlessness between the 1948 and the 1968 birth cohorts (Fig. 8.2). It is worth noting that the fertility rate of unmarried black women was almost twice the rate of unmarried white non-Hispanic women. Nonetheless, the decline in black fertility, overall and especially of unmarried – cohabiting and never married – women, was apparently the decisive factor in the recent rise of black childlessness.

6 Epilogue

More than ever in U.S. history, women and couples can regulate their fertility. They have access to a wide variety of means to prevent childbearing, and there is over 20 years of experience with assisted reproductive technologies (ART) which can alleviate the burden of infertility. A Division of Reproductive Health at the Centers for Disease Control has a long history of surveillance and research in women’s health and fertility, adolescent reproductive health, and safe motherhood. In response to a congressional mandate, CDC has started to strengthen existing data collection efforts initiated by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART), and to develop a national system for monitoring ART use and outcomes.

The facts, i.e. the childlessness levels and trends since the late nineteenth century, are reasonably well known. But often the mechanisms that shaped the facts have not been thoroughly deciphered, although some of the basic circumstances affecting levels and trends of childlessness are quite obvious, namely the concurrent economic and social conditions and cultural norms.

The U.S. population has experienced periods of very high and very low childlessness. The challenging living conditions in the 1930s appear to have been the main cause of the high levels of childlessness observed in that period. In contrast, the favorable living standards and enlightened public policies of the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s were instrumental in maintaining low levels of childlessness.

Living conditions of African Americans were far more difficult than those of white Americans; hence higher black than white childlessness during much of the twentieth century. Subsequently black childlessness declined to levels below those of whites which in part was likely to have been due to improvements in the health and living conditions of blacks, even though these conditions continued to be inferior to those of whites.

In the recent past, i.e. since the 1970s through the late 1990s/early 2000s, the three independent sources of data indicate that the overall childlessness rate doubled (Figs. 8.1, 8.2, 8.3 and 8.4 and Tables 8.1 and 8.2). This was the case among white as well as among black women, although not quite for identical birth cohorts (Fig. 8.2).

While history provides a general understanding of the principal causes of childlessness, the experience of the past few decades points to the complexity inherent in identifying more specific factors shaping levels and trends of childlessness. In Sect. 8.4 above, 15 such societal factors discussed in the literature are listed. In addition, people claim to have personal motivations and preferences for not having children. Six of the most compelling ones were also listed above. What appears lacking is an overall picture of the interaction of the elements which shape childlessness, and how these change over time.

As of the early 2010s, around 12–16 % of U.S. white and black women over age 40 remained childless. Among Hispanic women this share was lower, about 11 % were childless. Whether these percentages will increase or decline is impossible to predict. It depends on whether the material world will be aiding or obstructing family formation, and how cultural norms and personal attitudes will change over time.

Notes

- 1.

The levels of and trends in childlessness among women are based primarily on data from the Current Population Surveys in Table 8.1, which is generally corroborated by data from the cohort fertility tables (Fig. 8.2, 1970 cohort) and from the National Surveys of Family Growth (Table 8.2, latest years).

- 2.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) defines Hispanic or Latino as “a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race.” In data collection and presentation, federal agencies are required to use a minimum of two ethnicities: “Hispanic or Latino” and “Not Hispanic or Latino.”

Literature

Abma, J. C., & Martinez, G. M. (2006). Childlessness among older women in the United States: Trends and profiles. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 1045–1056.

Adams, C. (2013, March 14). Millions went to war in Iraq, Afghanistan, leaving many with lifelong scars. McClatchy Newspapers, http://www.mcclatchydc.com/news/nation-world/national/article24746680.html. Accessed 27 July 2015.

Anonymous. (2009, December 30). Female power. The Economist, http://www.economist.com/node/15174418. Accessed 27 July 2015.

Bachu, A. (1995). Fertility of American Women: June 1994. U.S. Bureau of the Census. Current population reports, populations characteristics (P20-482). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Banks, R. R. (2011). Is marriage for White people? How the African American marriage decline affects everyone. New York: Dutton.

Bianchi, S. M. (2011). Changing families, changing workplaces. Future of Children, 21, 15–36.

Cherlin, A. J. (2009). The marriage-go-round: The state of marriage and the family in America today. New York: Vintage Books.

Cherlin, A. J. (2014). Labor’s love lost: The rise and fall of the working-class family in America. New York: The Russell Sage Foundation.

Cohn, D’V., Passel, J. S., Wang, W., & Livingston, G. (2011). Barely half of U.S. adults are married. A record low. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2011/12/14/barely-half-of-u-s-adults-are-married-a-record-low/. Accessed 27 July 2015.

Copen, C. E., Daniels, K., Vespa, J., & Mosher, W. D. (2012). First marriages in the United States: Data from 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports, 49, 1–21.

Copen, C. E., Daniels, K., & Mosher, W. D. (2013). First premarital cohabitation in the United States: 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports, 64, 1–15.

DeNavas-Walt, C., Proctor, B. D., & Smith, J. C. (2012). Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2011 (P60-243). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). (2014). What’s next: Future global trends affecting your organization – Evolution of work and the worker. SHRM Foundation.

Espenshade, T. J. (1985). Marriage trends in America: Estimates, implications, and underlying causes. Population and Development Review, 11, 193–246.

Farber, H. S. (2010). Job loss and the decline in job security in the United States. In K. G. Abraham, J. R. Spletzer, & M. Harper (Eds.), Labor in the new economy (pp. 223–262). Chicago: Chicago Press.

Farley, R. (1970). Growth of the black population. Chicago: Markham Publishing Co.

Foster, C. (2000). The limits to low fertility: A biosocial approach. Population and Development Review, 26, 209–234.

Frejka, T. (2011). The role of contemporary childbearing postponement and recuperation in shaping period fertility trends. Comparative Population Studies – Zeitschrift für Bevölkerungswissenschaft, 36, 927–958.

Fry, R., & Kochhar, R. (2014). America’s wealth gap between middle-income and upper-income families is widest on record. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/12/17/wealth-gap-upper-middle-income/. Accessed 27 July 2015.

Goldstein, J., Sobotka, T., & Jasilioniene, A. (2009). The end of lowest-low fertility? Population and Development Review, 35, 663–700.

Hamilton, B. E., & Cosgrove, C. M. (2010). Central birth rates, by live-birth order, current age, and race of women in each cohort from 1911 through 1991: United States, 1960–2005. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics. [2012 addition with 2006–2009 data] http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/cohort_fertility_tables.htm. Accessed 27 July 2015.

Hašková, H. (2007). Fertility decline, the postponement of childbearing and the increase in childlessness in Central and Eastern Europe: A gender equity approach. In R. Crompton, S. Lewis, & C. Lyonette (Eds.), Women, men, work and family in Europe (pp. 76–85). Basingstoke/Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Heuser, R. L. (1976). Fertility tables for birth cohorts by color: United States, 1917–73. Rockville: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, National Center for Health Statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/fertiltbacc.pdf. Accessed 27 July 2015.

Karoly, L., & Panis, C. W. A. (2004). The 21st century at work forces shaping the future workforce and workplace in the United States. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation.

Kohler, H.-P., Billari, F. C., & Ortega, J. A. (2002). The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Population and Development Review, 28, 641–680.

Komarovsky, M. (1940). The unemployed man and his family. New York: Octagon Books.

Krugman, P. (2007). The conscience of a liberal. New York: W. W. Norton.

Laughlin, L. (2013). Who’s minding the kids? Child care arrangements: Spring 2011 (Current population reports P70-135). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Osterman, M. J. K., Curtin, S. C., & Mathews, T. J. (2015). Births: Final data for 2013. National vital statistics reports. 64.. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics.

Martinez, G., Daniels, K., & Chandra, A. (2012). Fertility of men and women aged 15–44 years in the United States: National survey of family growth, 2006–2010. National Health Statistics Report 51. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics.

Massey, D. S. (2011). The past and future of American civil rights. Daedalus, 140, 33–54.

McFalls, J. A. (1973). Impact of VD on the fertility of the US black population, 1880–1950. Social Biology, 20, 2–19.

McQuillan, J., Greil, A. L., Scheffler, K. M., & Tichenor, V. (2008). The importance of motherhood among women in the contemporary United States. Lincoln: University of Nebraska.

Morgan, S. P. (1991). Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century childlessness. American Journal of Sociology, 97, 779–807.

Mosher, W. D., & Bachrach, C. A. (1982). Childlessness in the United States. Journal of Family Issues, 3, 517–543.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1994). Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Population and Development Review, 20, 293–342.

Rindfuss, R. R., Morgan, S. P., & Swicegood, G. (1988). First births in America: Changes in the timing of parenthood. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Saez, E., & Zucman, G. (2014). Wealth inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from capitalized income tax data (Working Paper 20625). New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Scott, S. S. (2009). Two is enough: A couple’s guide to living childless by choice. Berkeley: Seal Press.

Sobotka, T. (2009). Shifting parenthood to advanced reproductive ages: Trends, causes, and consequences. In J. Tremmel (Ed.), A young generation under pressure? (pp. 129–154). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer.

Tsai, T., & Scommenga, P. (2012). U.S. has world’s highest incarceration rate. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau.

US Bureau of the Census. (1975). Historical statistics of the United States, colonial times to 1970. Washington, DC: Bicentennial Edition.

US Census Bureau. (2012). The 2012 statistical abstract. http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/. Accessed 27 July 2015.

Wang, W., Parker, K., & Taylor, P. (2013). Breadwinner moms: Mothers are the sole or primary provider in four-in-ten households with children; public conflicted about the growing trend. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/05/29/breadwinner-moms/. Accessed 27 July 2015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Frejka, T. (2017). Childlessness in the United States. In: Kreyenfeld, M., Konietzka, D. (eds) Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, Causes, and Consequences. Demographic Research Monographs. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44667-7_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44667-7_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-44665-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-44667-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)