Abstract

Childlessness in the central European Alpine countries of Switzerland and Austria is high by western standards: around a fifth of men and women in these countries have no children towards the end of their reproductive life. This chapter looks at variations in childlessness across six spheres: cohort, education, religion, country of birth, language, and place of residence. For Switzerland, the differentials for both men and women are described; for Austria, only data for women are available, but they tell a parallel story. Although many of the attributes are closely interlinked, some over-arching factors clearly increase the likelihood of childlessness. In the case of education, the effect is the opposite for women and men: highly educated women and less educated men face barriers in having a family. Competing with education for the degree of influence on childlessness is having no religious affiliation; unlike education, this factor is associated with a reduced desire to have a child. At the other end of the spectrum, low levels of childlessness are observed among immigrants from southern Europe and the Muslim sub-population.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Childlessness

- Cohort fertility

- Country of origin

- Educational level

- Fertility intentions

- Religious affiliation

- Spatial differentials

1 Introduction

For several reasons, Switzerland and Austria are of interest to researchers analysing the factors that influence levels of childlessness. The countries are similar in terms of population size, standard of living, and socio-economic setting. The Alpine regions have traditionally had rather high levels of childlessness, with a significant proportion of women and men remaining single (Viazzo 1989). The current population of Switzerland is about 8.2 million, of whom 65 % are German-speaking, 23 % are French-speaking, and 8 % are Italian-speaking. As each canton has its own official religion and language(s), there are French- and German-speaking Catholic, Protestant, and secular cantons. In the age range 20–39 a third of the population has foreign citizenship. These immigrants come not only from the neighbouring countries of Germany, France, and Italy, but also from ex-Yugoslavia, Portugal, and Spain. Austria has a slightly larger population, at 8.6 million, and the official language is German, with 89 % of the population speaking German as their mother tongue. The proportion of foreigners in the country is less than half that of Switzerland, with immigrants from Germany and the countries of ex-Yugoslavia and Turkey being the most numerous. Around 20 % of women in Switzerland who have reached the end of their reproductive years have no children, while the corresponding figure in Austria is a little lower, at around 18 %. In Switzerland, the share of the population who are childless has never been lower than 14 % even for the cohorts who lived through the baby boom years, whereas in Austria it dropped to around 12 %. These levels and trends are similar to those of some countries in western Europe (the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands) and a few overseas developed countries (the United States, Japan), but are very different from central and eastern Europe, which have much lower rates of childlessness.

This chapter examines the differentials in fertility outcomes across sub-populations in the two countries, drawing on census and survey data. Specifically, we examine the variations in levels of childlessness by cohort, educational attainment, religion, migration background, and current place of residence in the country. We also provide insights into differences in fertility desires in the two countries.

2 Institutional Setting and Data

2.1 Institutional Setting

In Austria, the parental leave period is up to 3 years, and because the conditions for taking this leave are relatively generous,Footnote 1 it is widely used. Only one-third of mothers with children under age three are in the labour force, well below the OECD average of 41 % (OECD 2014). Just 21 % of children under age three were in public day-care in Austria in 2012, which is the lowest proportion among all of the western European countries. As childcare in Austria is administered by municipalities, there are big disparities in childcare provision between the regions. The availability of day-care has been increasing in Vienna, and the proportion of children under age 3 who are enrolled has grown from 17 % in 1995 to 35 % currently. Participation rates have generally been high for children aged 4–5, and have recently increased considerably among 3-year-olds, from 40 to 50 % in the 1990s to 81.5 % in the 2012/13 school year (Statistics Austria 2013a). Women in Austria have a legal right to reduce their working hours to part-time after having a child, and many women take advantage of this option. Among couples with children ages 0–14, the proportion of families in Austria with one parent working full-time and the other working part-time was 44 % in 2011, the highest share amongst all OECD countries except for the Netherlands with 60 % (OECD 2014). Public spending on the family is very biased towards cash benefits (such as parental leave and child allowances) rather than services (pre-school childcare, or policies to help parents combine work and childrearing). As Neyer and Hoem (2008: 94) noted, “Austria represents a conservative, gendering welfare state which supports mother’s absence from the labor market”.

In Switzerland, by contrast, there is less public support for new families. Maternity leave is only 14 weeks and childcare facilities are scarce and expensive, especially in the German- and Italian-speaking areas of the country. High incomes and the widespread availability of part-time jobs only partially offset the challenges facing couples with small children; the opportunity costs of a break in employment to have a child are higher in Switzerland than in most other countries. The female labour force participation rate of women aged 25–39 has been increasing, and was 85 % in 2014. While 80 % of employed women living in a household with child(ren) under the age of 15 are working part-time, the corresponding proportion of men with young families who are working part-time remains low, but increased from 3 % in 1992 to 10 % in 2014 (Federal Statistical Office 2015a).

2.2 Data

In this chapter, the primary data source for Switzerland is the full population census taken in the year 2000. The census asked both women and men to state the number of children they had ever borne or fathered. The question on number of children was not compulsory, and around 3 % of women did not respond. This proportion was a little higher for men, and was markedly higher among young and elderly people, who may have considered the question irrelevant. Foreigners also had an elevated non-response rate, of around 7 %.

Austria has similar census data, which in 1981, 1991, and 2001 included fertility data. Women aged 16 and over were asked to report the number of live-born children they had ever had. Because of the way the census question was posed, there were some discrepancies in the proportion of respondents who said they were childless among comparable cohorts between the 1981 survey and subsequent surveys (Zeman 2011). For this chapter, we mainly use the 2001 census data.Footnote 2

Birth registration data for the years since the last census, together with population estimates from registers, allow for the calculation of age- and birth order-specific fertility rates, and thus enable us to make on-going estimates of cohort fertility. For Switzerland and Austria, these base data are available in the Human Fertility Database (2015).

Surveys of various sizes and spheres of interest are used to complement the census and birth registration data for both Switzerland and Austria. In 1994, Switzerland participated in the multi-national Fertility and Families Survey (FFS). More up-to-date information was gathered in 2013 with the Families and Generations Survey (FGS). This survey, which had a sample size of over 17,000, included information on family sizes and fertility intentions, along with many other demographic variables. Another on-going survey that offers insights into fertility in Switzerland is the Swiss Household Panel (SHP). In Austria, a micro-census of around 22,500 households is performed four times a year, and includes many socio-economic variables, with a focus on the labour market. Special modules asking about the number of children and fertility intentions (Kinderwunsch) are included about every 5 years (1986, 1991, 1996, 2001, 2006, and 2012). In this chapter we use the individual micro-data from the micro-census wave of the fourth quarter of 2012.

3 Childlessness by Socio-economic Characteristics

3.1 Changing Levels of Childlessness by Birth Cohort

Figure 6.1 shows the trends in cohort fertility for Austria and the corresponding proportions of women born between 1920 and 1960 who were childless. In earlier generations, the rates of childlessness were even higher: among the cohorts born in the 1880s and 1890s, around one-third of the women remained childless in both Switzerland and Austria (Viazzo 1989). In traditional societies a substantial proportion of the population did not marry for a variety of reasons. For example, many people were discouraged or prohibited from marrying by family inheritance systems; poverty and the inability to raise enough money to marry; choosing to enter into religious orders; or legal restrictions on the right to marry for members of the lower classes (Mantl 1999). In addition, a significant proportion of married women remained childless because, for example, they suffered from infectious diseases or were infertile, their pregnancies ended in miscarriage or still-birth, or they were widowed or separated from their partner for long periods of time (Ehmer 2011).

The lowest level of childlessness in Austria, at around 12 %, was reached for women born in 1938. The childlessness rates among subsequent cohorts increased steadily, rising to around 18 % for women born around 1970. In 1984, only 11 % of first births occurred after age 30, and just 0.3 % of births occurred after age 40. In 2013, the corresponding figures were 45 % and 2.3 %, which represents a significant shift. As women are postponing the birth of their first child to increasingly high ages, the risk of infertility is rising, and is only partially offset by the increasing availability of assisted reproductive technology (ART). In Austria, public health care provides subsidised ART to infertile women, and 2 % of live births resulted from the use of ART in 2010 (ESHRE 2014).

Switzerland has fertility data for both men and women (see Fig. 6.2), and while the levels and trends in Switzerland are similar to those of Austria, they are not identical. The lowest childlessness rates were for the 1932 male cohort and the 1936 female cohort. It is interesting to note that for the cohorts born before 1940 childlessness was higher for women, but among the more recent cohorts childlessness has been higher for men. There is no clear explanation for this shift. It is possible that men of earlier generations would seek a new partner if their first wife did not bear them a child, as the pressure to produce an heir, especially in rural communities, may have been significant. Among more recent generations, the situation may be reversed, as an increasing proportion of less skilled men are failing to find a partner. The different life courses and work constraints of male and female immigrants and low skilled workers, and how they have changed over time, may also explain the differential.

The baby boom was associated with a double peak in period fertility rates. In Austria, the highest TFRs were 2.75 in 1940 and 2.82 in 1963, while Switzerland’s peak TFRs were a little lower, at 2.62 in 1946 and 2.68 in 1964. An upsurge in early births was a major cause of the temporal peaks in period fertility; whilst postponement, together with the decline in large families, has depressed period rates since the baby boom. Although the period trends were similar in Austria and Switzerland, the cohort fertility trends in the two countries were rather different. In Austria there was a peak of 2.5 children on average, for women born in the mid-1930s, followed by a decline to 1.75 for the 1960 cohort (Fig. 6.1). In Switzerland the average family size was quite stable at around 2.2 children for the cohorts born up to the mid-1930s. Subsequent cohorts then experienced declines to the current level of around 1.75.

3.2 Childlessness by Education

A large number of studies have shown that, for women, having more education is associated with lower overall fertility and higher rates of childlessness (for a general overview, see Skirbekk 2008; for Austria, see Neyer and Hoem 2008, Prskawetz et al. 2008, Sobotka 2011; for Switzerland, see Coenen-Huther 2005, Sauvain-Dugerdil 2005, and Mosimann and Camenisch 2015; for other countries, see Wood et al. 2014). For an analysis of the link between childlessness and field of education, see the chapter by Neyer et al. in this volume.

Over the past century, educational levels have been rising, particularly for women. In Switzerland, for example, the proportion of women who have tertiary-level education increased from 6 % of those born in 1930, to 13 % of those born in 1950, to 21 % of those born in 1970, and it is still rising. The corresponding figures for men born in 1930, 1950, and 1970 are 24 %, 30 %, and 33 %, respectively. We might expect to find that with higher education becoming more prevalent, the reproductive behaviour of highly educated women would become less differentiated from that of less educated women. Interestingly, Austria has seen such a convergence (Fig. 6.3), whereas Switzerland has seen a divergence (Fig. 6.4). Austria differs from most other developed countries in that men are still more likely than women to enrol in tertiary education; whereas in most other European countries, including in Switzerland, women now outnumber men in higher education.

Proportion of women who were childless by birth cohort and level of education, Austria. Note: The primary level includes ISCED 1997 levels 0–2; the lower secondary level includes ISCED levels 3B and 3C; the higher secondary level includes ISCED levels 3A and 4; and the tertiary level includes all ISCED levels of 5 and 6 (Source: Census 2001, own estimates)

Proportion of women who were childless by birth cohort and level of education, Switzerland. Note: The primary level includes ISCED 1997 levels 0–2; the lower secondary level includes ISCED levels 3B and 3C; the higher secondary level includes ISCED level 3A; and the tertiary level includes all ISCED levels of 5 and 6 (Source: Census 2000, own estimates)

The 1981 Austrian census showed that around 60 % of the women born in the 1890s and early 1900s who had a tertiary education were childless: thus, their decision to pursue a higher education was effectively a “life calling” similar to the calling to commit to a celibate life in the church. Among the cohorts born after the Second World War in Austria, there has been a convergence in childlessness rates between women at the upper two educational levels, and between women at the lower two educational levels; the differentiating factor is whether or not a woman graduated from secondary school with a high school diploma (Matura) (Fig. 6.3). This pattern may be caused by Austria’s early educational streaming of pupils after the fourth year of elementary school into either vocational training or a higher secondary and university track, with limited opportunities to transfer between the two. This educational system has been described as being “segregated by gender and social class” (Neyer and Hoem 2008: 107).

Figure 6.4 shows the incidence of childlessness for women of different educational levels in Switzerland. Among women with a low educational level, the rates are similar for Switzerland and Austria, at around 15 % of the current generation completing their childbearing. However, for women with tertiary education, the rates of childlessness differ considerably between the two countries: one-third of these women in Switzerland are childless; whereas in Austria only around one-quarter are childless, which is similar to the rate for women with higher secondary education. Moreover, unlike in Austria, in Switzerland the two secondary education groups recently converged at a level of about 20 %. In Austria there are now two distinct groups: moderate rates of childlessness among women with primary or lower secondary education, and higher rates of childlessness among women with tertiary or higher secondary education. In Switzerland, however, three groups have emerged: moderate rates of childlessness among women with primary education, higher rates of childlessness for those with secondary education, and the highest rates of childlessness for women with tertiary education.

The differentials in childlessness by education for men are much smaller than those for women (see Fig. 6.5 for Swiss data). Among the older generations, lower educated men had the highest rates of childlessness, most likely caused by poverty. There is a transposition in ranking among younger men, with an intermediate level of academic attainment being associated with the highest levels of childlessness. It was still possible that the men born after 1955 (who were under age 45 at the time of the census) could father a child.

Proportion of men who were childless by birth cohort and level of education, Switzerland. Note: The primary level includes ISCED 1997 groups 0–2; the lower secondary level includes ISCED levels 3B and 3C; the higher secondary level includes ISCED levels 3A and 4; and the tertiary level includes all ISCED levels of 5 and 6 (Source: Census 2000, own estimates)

3.3 Childlessness by Religion

Back in 1994, the Swiss FFS found that religiosity was associated with different views on the benefits of having children (Coenen-Huther 2005). The findings indicated that compared with respondents who were active in their faith, those with no religious affiliation were less likely to believe that having children offers benefits such as joy and satisfaction, partnership consolidation, and continuation of the family line. In addition, the respondents who did not attend religious services were less likely to see children as a potential support when elderly, or as a continuation of life after their death. It is, therefore, not surprising that religiosity has an impact on fertility outcomes.

Both Austria and Switzerland are more religious than many other western European countries, with up to one-quarter of all adults regularly attending a religious service. In Austria the majority religion is Catholic; 61 % of Austrians are members of the Catholic Church, whilst around 5 % are members of Protestant churches. In Switzerland there is a more even split between the Catholic and the Reformed (Protestant) denominations, and affiliation with these churches is mixed across both regional and linguistic lines. In both countries the proportion of the population with no religious affiliation is growing, and young people attend religious services much less frequently than older people (Burkimsher 2014). In Switzerland, religious affiliation was recorded in the 2000 census. For Austria, census data from 2001 is available for women in Vienna, obtained as part of the WIREL project (see Acknowledgements).

There is a close relationship between educational level and religious affiliation. Most notably, those who classify themselves as having “no religion” have, until recently, been more concentrated among the highly educated. Recent evidence suggests, however, that among the younger generations (those born after the 1960s) this link is weakening or even reversing.

In general, the differences between Catholics and Protestants in rates of childlessness are slight in both Switzerland and Austria. However, very significant differences appear when we look at the non-religious. Holding other factors constant, the childlessness rate of the non-religious is about double that of Catholics and Protestants in Switzerland. This result contradicts the findings of Baudin (2008) for France: that (non-)religiosity has a significant effect on family size, but not on the likelihood of remaining childless. The differential between Catholics and those with no religion is not quite as marked in Austria (Vienna) as in Switzerland, but it is still significantly large.

Vienna is a very heterogeneous city in which all the major religions are represented. In the 2001 census the level of childlessness for 45–54-year-old women was 20 % for both Catholics and Protestants. Among Muslim and Orthodox women the childlessness levels were significantly lower, at 8 % and 9 %, respectively. In contrast, the childlessness level for women with no religious affiliation was significantly higher, at 26 %. When we take into account country of birth and education in our analysis, the distinctiveness of Muslim and Orthodox women becomes weaker, which suggests that the very low levels of childlessness among these women is attributable in part to their migration background and low educational attainment. In Vienna, the factors of education and country of birth have greater effects on childlessness than religion per se.

In a recent study that focused on women scientists in Austria, Buber-Ennser and Skirbekk (2015) found that education (along with age and marital status) was the most important determinant of actual childlessness; and that religious affiliation, whilst still having significant explanatory power, had a weaker effect. In contrast to actual childlessness, differentials by religiosity in the intention to remain childless were large. However, there were no significant differentials in fertility intentions by education when religion was taken into account (but a significant proportion of highly educated women fail to achieve their fertility ambitions). The same pattern was found for men and women in the FGS in Switzerland: i.e. the non-religious were much more likely than the religious to say they did not want to have a child, but the differentials in actual childlessness were smaller.

In Switzerland, the effects of having a higher education and no religious affiliation are multiplicative: for women born in the 1960s, almost 45 % of those who were both tertiary educated and had no religious affiliation were childless. From the 1920s cohort to the 1960s cohort an increasing proportion of the population (4–12 % of women) embraced the “no religion” position. At the same time, their fertility behaviour, perhaps surprisingly, became increasingly differentiated from that of women who were traditional Catholics/Protestants. But among younger cohorts there are indications that the patterns in Switzerland and Austria are becoming increasingly similar to those observed in Britain (Dubuc 2009): i.e. as the lower educated increasingly describe themselves as having no religion, the historical association between having no religion and a high rate of childlessness is starting to break down.

In contrast to the traditionally Christian background of the local population, the Muslim (predominantly immigrant) communities are distinctive in their partnering and fertility behaviour (Fig. 6.6). Almost all Muslims marry, and within marriage childlessness is rare; probably around the biological minimum. There is a norm of early marriage and childbearing: at age 30 (in 2000) only 6 % of Muslim women were still unmarried, and 84 % had had at least one child.

3.4 Childlessness by Country of Birth

In Switzerland, and to a lesser extent in Austria, very high proportions of the young adult population were born outside of the country. Their reasons for being in the country, as well as the strong influences of education and religion, as already discussed, affect their levels of childlessness.

On average, immigrants have a lower rate of childlessness than the native-born. However, closer investigation reveals that there are big differentials by country of origin. Censuses record either current citizenship (Austria in 1981 and 1991) or country of birth (Austria in 2001); or they record both (Switzerland in 2000). These categories are not directly equivalent, as the relative ease or difficulty of naturalisation determines how many immigrants acquire citizenship; it is easier to become a citizen in Austria than in Switzerland, and it is easier for some nationalities than others to acquire citizenship in both countries. In both Switzerland and Austria, being born in the country does not confer the automatic right to that country’s citizenship. Table 6.1 shows the proportion of the total population by citizenship, and by whether they were born in the country.

In general, people with foreign citizenship have a younger age profile than all people “born abroad”, because immigrants who stay in the country longer often aspire to citizenship. Having children in the country also tends to be associated with settling or remaining for a longer period of time. The outcome of these factors in terms of childlessness is illustrated in Table 6.1 for Austria. The 1981 census showed that the childlessness level of women with foreign citizenship was ten per cent higher than that of Austrian women. This reflects the fact that in the 1960s and 1970s many immigrants came from Western Europe for short- and medium-term work, and they made up a very small share of the population (1.5–3 % of the 1920–1940 cohorts). In the 2001 census, when country of birth was recorded, the differentials were much lower, and among women younger than age 50 there was a reversal, with immigrants having lower levels of childlessness than the native-born. The reason for this shift is that in the 1990s more immigrants came from the war-torn countries of former Yugoslavia, and later from Turkey; and these migrants, who were especially likely to settle and have a family in Austria, had higher fertility rates than the native population. These immigrants also made up a much larger share of the population than other groups of foreign citizens (10–14 % of the 1920–1940 cohorts) (Fig. 6.7).

For Switzerland, we have more detailed information on childlessness rates by country of birth from the 2000 census. Table 6.2 shows the rates for a selection of countries and regions to illustrate certain factors that have a bearing on childlessness. A higher rate of childlessness is associated with coming from a culture in which childlessness is quite common, especially amongst highly educated women. This can explain the high rates for women from the Anglo-Saxon countries, Finland, Germany, and the Netherlands; as well as from the developed countries of the Far East, including Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. In contrast, childlessness is low among women from southern Europe, the Balkans, and Turkey, as in those countries childlessness is rare. However, the high rates of childlessness among women from the ex-communist countries are surprising, as the rates were traditionally very low in these countries.

For some immigrants, the constraints imposed by their specific work conditions in Switzerland can have a significant impact on their rates of marriage and childbearing. The high levels of childlessness among women from the Philippines, Thailand, and Latin America is likely attributable to the fact that many come to work as maids or nannies. The childlessness rates are significantly lower for men from these countries than for women. Immigrants from some countries find a restricted “marriage market” in the country, caused by a gender mismatch in the number of immigrants from the same culture. As was already mentioned, this mismatch partly explains the higher rates of childlessness for women than men from less developed countries. Similarly, it explains why childlessness is higher for men compared to women coming from Spain and Italy. Many single young men come from these countries to work in physically demanding jobs, often on a short- or medium-term basis; if they marry, they often return to their home countries.

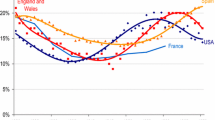

We can see the influence of these factors playing out if we compare German, French, and Italian speakers by their respective places of birth: i.e., Switzerland, Germany, France, or Italy (Figs. 6.8, 6.9, and 6.10).

As we noted earlier, the childlessness level for Germans is rather high, and the differential between native Swiss-Germans and immigrant Germans is getting larger with younger cohorts. Childlessness is particularly common for German women living in Switzerland: it is nearly 35 % for the 1960 cohort, compared to “only” 25 % for the Swiss-Germans of the same cohort.

The graph for French speakers (Fig. 6.9) is quite different from that for German speakers in Switzerland. The childlessness rates for French speakers are lower than the rates for German speakers, and the differences by country of birth (France or Switzerland) are much smaller. For men the gap between the two groups is insignificant, although for women immigrating from France, the rate is a couple of percentage points higher.

Figure 6.10, which shows the patterns of childlessness for Italian speakers, is different again. Immigrants from Italy have very low levels of childlessness; lower even than those of native Italians in Italy. The proportion of native-born Italian speakers–most of whom live in the canton of Ticino–who are childless is even higher than in the German-speaking parts of the country. In this Alpine region, there is a long-established tradition of marrying late, and a high rate of singlehood. This may be an adaptation to life in a rugged region, where population pressures were mitigated by a division into high-fertility “family” women and men, and those who remained single and had other specific roles to play in society (Viazzo 1989). The low, though steadily increasing rates of childlessness among Italian immigrants may be explained by their origin in southern Italy, where fertility behaviour follows the southern European pattern.

3.5 Geographical Variations in Childlessness and the Process of Concentration

Childlessness has traditionally been considerably higher in Vienna than in the rest of Austria, for two main reasons: first, a large proportion of the city’s population are single, many of them students or seasonal migrants; and, second, there is selective outmigration of young families to the periphery of Vienna, which is mostly in the province of Lower Austria. Table 6.3 gives the proportion of women who are childless at ages 45–54 (i.e., the birth cohorts of 1958–1967) by province (Bundesland) based on the micro-census Q4/2012 data. Most of the regions have a childlessness level of around 11–15 %, whereas in Vienna it is nearly 26 %. Another region with high rates of childlessness is Burgenland, a small region of mixed ethnicity in the Vienna outer commuter belt bordering Hungary and Slovenia: there, the childlessness level is nearly 20 %.

Using data from the Geburtenbarometer (2014), and extrapolating the trends in age-specific fertility rates, we can project that any increase in childlessness will be modest, reaching perhaps 19 % for Austria as a whole. In Vienna, on the other hand, childlessness is forecast to decline, from 27 % to 21 %. Figure 6.11 shows this expected convergence. Among the 19–29 age group, the mean intended family size for women in Vienna is identical to that of Austria as a whole, at 1.8; and the proportion of women who intend to stay childless is also the same, at 12 % (Mikrozensus Q4/2012).

Childlessness among women in Vienna and Austria as a whole: Known rates and projections extrapolating current trends of age-specific fertility rates, Austria and Vienna (Source: Geburtenbarometer (2014), own estimates)

When we analyse variations by type of settlement, we can see that for women aged 45–54 the childlessness rate was around 8–9 % in agricultural areas, 12 % in rural areas, 15 % in small towns, 19 % in larger towns, and 27 % in Vienna. A similar pattern has been found in Switzerland (Wanner 2000). The 2013 FGS showed that the proportion of women aged 45–54 who were childless was 27 % in the major cities (Zürich, Geneva, Basel, Lausanne, Bern, and Winterthur), 20 % in other towns, and 18 % in rural areas. Among men of the same age, the childlessness rate was 43 %, 22 %, and 20 % for the respective areas. When we look at the map derived from the Swiss census data of 2000, which shows the relative levels of childlessness for 45–49-year-old women (Fig. 6.12), we can see clear concentrations of childlessness in the major urban areas, especially around Zürich and Bern, across much of the canton of Ticino, and in some pockets of the high Alpine areas.

4 Fertility Intentions

Respondents are asked about their ideal family size in many social surveys, and the results indicate that the two-child family ideal is still widespread across Europe (Sobotka and Beaujouan 2014). However, for many young people this is a hypothetical question, with a distinction between general family ideals and individual fertility intentions or desires. There are several major hurdles individuals have to clear before they can consider having a child: finding a (suitable) partner, resolving any conflicts between life goals, and being able to offer a child a good start in life (by having access to, for example, adequate housing, sufficient income, employment security, and child care). For women, all of these conditions have to be met while they are still in their reproductive years. It is, therefore, not surprising that expressed desires are fluid until the reproductive clock has finally stopped ticking. Even if a significant proportion of children are still unplanned, most people will seek to fulfil at least some of the pre-requisites before becoming parents.

From the 1994 Fertility and Family Survey (FFS) of Switzerland it was apparent that the desire to have children changes as people move through their adult life (Gabadinho and Wanner 1999). While 7 % of female respondents in their early twenties said they intended to remain childless, this figure fell to 2 % for respondents aged 25–29, before rising again for respondents in their 1930s. Among male respondents, the proportion who said they plan to remain child-free was slightly higher than that of women until they reached their late thirties. At that life stage, most of the women who had not had children accepted that they were unlikely to become a mother because of the path their life had taken; whereas some men, who are fecund for longer, indicated that they still hoped to become a father. The Swiss census confirmed that a few men do become first-time fathers even in their sixties and seventies.

The results of the Families and Generations Survey (FGS), which was undertaken in Switzerland in 2013, confirm these patterns and provide additional insights. As was shown by Mosimann and Camenisch (2015), having a low educational level appears to be associated with a reduced desire to have a child among young men, or it may reflect their limited potential for finding a partner. Among women, there is no difference based on educational level in the expressed intention to remain childless. Although women with a tertiary education are much more likely to end up childless, this does not reflect their stated aspirations when they were younger.

In Austria, family size ideals are below replacement level (Goldstein et al. 2003), with a relatively high proportion of women opting to remain child-free. According to the Eurobarometer 2011 survey, the mean intended number of children at ages 15–39 was 1.78, far lower than in any other country of Europe: the mean number was 1.9 in Romania and was two or more in all other countries, with an average of 2.3 across all of the surveyed countries (OECD 2014). For young men in Austria the intended number was even lower, at 1.55. At 11 %, the share of women in Austria who said they intend to remain childless was the highest among all of the countries in the survey. Educational level has been found to have a significant effect on fertility desires. Data from the micro-census Q4/2012 show that, at ages 19–34, the proportion of women who said they intend to stay childless was 7 % for those with low education, 10–12 % for those with completed secondary education, and 15 % for those with tertiary qualifications. By contrast, the final rates of childlessness for women aged 45–54 for these educational levels were 13–14 %, 16 % and 27 % respectively. This indicates that the differences in fertility intentions by level of education are smaller than the differences in fertility outcomes. A study by Buber et al. (2011) showed that, amongst a sample of 196 female scientists aged under 35 (PhD diploma holders who had applied for a grant at the Austrian Academy of Sciences), 11 % said they intended to remain childless, while the actual level of childlessness of similar women at age 45 was 44 %. Among the most important obstacles to childbearing cited were strong work commitment, the need to be geographically mobile, and the high prevalence of living-apart-together (LAT) relationships. The same sentiment was expressed by women in the Swiss Family and Fertility Survey, that their primary reason for not wanting to have a child was the problem of having to reconcile work and family (Coenen-Huther 2005).

The Swiss Household Panel survey sheds more light on the ambivalent fertility desires of individuals. From 2002 onwards the same group of respondents have been asked each year how many children they would ideally like to have. As they have been followed, it has become apparent that stated fertility intentions are volatile across the life course. Out of a sample of over 4000 respondents, for whom at least three survey waves were available and who were under age 38 in 2002, only 4 (0.1 %) stated they wished to have no children across all of the survey years. There was more stability in the responses of those who said they wanted to have at least one child, with over 57 % of the respondents falling into this category. However, a significant minority sometimes express the desire to have children and at others times say they do not (this does include some who actually have children). We can therefore deduce that while, on average, 11 % of respondents in any specific survey wave say they want no children, this is not a fixed trait: the blossoming (or breakup) of a romantic relationship may change their opinion (see Kuhnt et al. in this volume 11). The approach of menopause may increase the desire to have a child for some women, or extinguish it for others. The conflicting appeal of career versus motherhood—when there is a perception that these roles are incompatible—will influence the choice of a significant number of childless women (Mosimann and Camenisch 2015).

5 Conclusions and Discussion

Austria and Switzerland (along with Germany) share a pattern of low rates of fertility and high rates of childlessness which distinguishes them from other countries of Europe. Not all (developed) countries with relatively high levels of childlessness have low overall fertility. In some countries, such as the Nordic countries and the UK, the significant proportion of larger families compensates for the rather high levels of childlessness (see Berrington in this volume 3). In a western context, the countries that have a wide range of family forms and family sizes (including childlessness), and that allow for flexibility in the timing of childbearing, currently have higher fertility rates than countries in which fertility behaviour is more uniform. In Austria and Switzerland traditional norms tend to dominate.

Medical advances have changed patterns of childbearing, as women are able to postpone parenthood with the use of efficient contraceptives, and older women are able to have children using ART. However, many constraints remain, as the previous sections in this chapter have shown. Among these constraints are the varying degrees of desire to have a child. For example, German speakers are somewhat less family-oriented than French and Italian speakers. Moreover, the desire to have a child is not always fulfilled: for example, people who live in the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland apparently find it more difficult to meet their fertility goals. They have a low desire for childlessness, yet actual levels of childlessness are similar to those of the German-speaking region. It is unclear whether this gap is mainly attributable to the limited childcare facilities in Ticino, or to the legacy of traditional Alpine family formation patterns, as described by Viazzo (1989). In contrast, marriage rates in the French-speaking parts of Switzerland are lower than in the German- and Italian-speaking areas, yet childlessness is also less common: this reflects the higher incidence of extramarital fertility in the French-speaking region, which resembles that of France to some extent.

Men and women who classify themselves as having “no religion” have a much lower desire to have children than the religiously affiliated, and have lower marriage rates; as a consequence, they are more likely to remain childless. In addition, the Swiss census shows that a very high proportion—about one-third—of non-religious married men and women (secondary- and tertiary-educated) are childless. It would appear that the declaration of having no religion reflects life priorities that are different from those of people who are affiliated with religion to some degree. However, in Austria level of education and country of birth are more important explanatory characteristics of childlessness than religion itself, at least amongst women. In Switzerland, the influence of having no religion on childlessness has varied across cohorts, with the largest effect seen in women born in the 1950s, for whom the influence of being non-religious was even greater than that of having a tertiary education. Among men, education has a much smaller effect on the likelihood of being childless, with religion being the primary determinant across all cohorts.

At younger ages, the majority of women, regardless of their level of education, say they want two children (Mosimann and Camenisch 2015). It appears, however, that as life passes, highly educated women in particular face mounting constraints on their ability to fulfil their earlier expectations: they experience difficulties in finding a suitable life partner, reconciling the demands of a career and motherhood, and managing the practical issues of childcare.

The future trajectory of fertility in Austria and Switzerland will depend on whether women and men maintain their fertility intentions; whether partnering, marriage, and divorce patterns evolve; and whether the current hurdles faced by (for example) highly educated women can be overcome. The trends in the United States would suggest that the future could be brighter than is sometimes anticipated, as childlessness has been declining and fertility has been increasing amongst the highly educated (Livingston 2015 and Frejka, Chap. 8 in this volume). Where America is trending today, will Europe follow tomorrow? The projections for childlessness, calculated by Sobotka (in this volume), suggest that childlessness will indeed decline in Switzerland if current trends are maintained, and will rise only modestly in Austria, to around 20 %. Whether the differentials by sub-population are sustained remains to be seen.

Notes

- 1.

Since 2008 parental leave in Austria has been made more flexible, with three variants of duration of 18/24/36 months, which offer different levels of monthly allowances, of 800/624/436 EUR.

- 2.

Census data on parity by level of education, origin, and cohort are available in the Cohort Fertility and Education database (Zeman et al. 2014).

Literature

Baudin, T. (2008). Religion and fertility: The French connection (Working paper of the Centre de l’Economie de la Sorbonne). https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00348829/document Accessed 2 Sept 2015.

Buber, I., Berghammer, C., & Prskawetz, A. (2011). Doing science, forgoing childbearing? Evidence from a sample of female scientists in Austria (VID Working Paper 01/2011).

Buber-Ennser, I., & Skirbekk, V. (2015). Researchers, religion and childlessness. Journal of Biosocial Science, 47, 1–15.

Burkimsher, M. (2014). Is religious attendance bottoming out? An examination of current trends across Europe. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 53, 432–445.

Coenen-Huther, J. (2005). Le souhait d’enfant: un ideal situé. In J.-M. Le Goff, C. Sauvain-Dugerdil, C. Rossier, & J. Coenen-Huther (Eds.), Maternité et parcours de vie: L’enfant a-t-il toujours une place dans les projets des femmes en Suisse? (pp. 85–133). Berne: Peter Lang.

Dubuc, S. (2009). Fertility and religion in the UK: Trends and outlook. Paper presented at the population association of America conference 2009, Detroit.

Ehmer, J. (2011). The significance of looking back. Fertility before the “fertility decline”. Historical Social Research, 36, 11–34.

ESHRE. (2014). Results generated from European registers by ESHRE Human Reproduction, 29, 2099–2113 – Supplementary data. https://humrep.oxfordjournals.org/content/suppl/2014/07/27/deu175.DC1/deu175_suppl.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2016.

Federal Statistical Office. (2015a). On the way to Gender Equality. Current situation and developments. Economic and social Situation of the Population 619–1300. http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/en/index/themen/20/05/blank/key/Vereinbarkeit/01.html Accessed 19 Oct 2016.

Federal Statistical Office. (2015b). Population résidente permanente et non permanente selon Année, de population, Lieu de naissance et Nationalité. http://www.bfs.admin.ch Accessed 2 Sept 2015.

FFS. (1999). Fertility and family survey. Switzerland. Population activities unit, Economic Commission for Europe. Geneva: United Nations.

Gabadinho, A., & Wanner, P. (1999). Fertility and family surveys in countries of the ECE region. Standard country report: Switzerland. New York/Geneva: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

Geburtenbarometer. (2014). Vienna Institute of Demography. http://www.oeaw.ac.at/vid/data/geburtenbarometer-austria-and-vienna/. Accessed 20 Oct 2016.

Goldstein, J., Wolfgang, L., & Testa, M. R. (2003). The emergence of sub-replacement family size ideals in Europe. Population Research and Policy Review, 22, 479–496.

Human Fertility Database. (2015). Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany) and Vienna Institute of Demography (Austria). www.humanfertility.org Accessed 17 Feb 2015.

Livingston, G. (2015). Childlessness falls, family size grows among highly educated women. Pew Research Center; Social & Demographic Trends. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/05/07/childlessness-falls-family-size-grows-among-highly-educated-women/ Accessed 19 Oct 2016.

Mantl, E. (1999). Legal restrictions on marriage: Marriage and inequality in the Austrian Tyrol during the nineteenth century. The History of the Family, 4, 185–207.

Mikrozensus. (2012). Kinderwunsch – Zusatzfragen zur Mikrozensus-Arbeitskräfteerhebung Q4/2012. Statistics Austria.

Mosimann, A., & Camenisch, M. (2015). Families and generations survey 2013: First results. Federal Statistical Office, Neuchâtel, 7–8.

Neyer, G., & Hoem, J. M. (2008). Education and permanent childlessness: Austria vs. Sweden. A research note. In J. Surkyn, P. Deboosere, & J. van Bavel (Eds.), Demographic challenges for the 21st century. A state of art in demography (pp. 91–114). Brussels: VUBPRESS.

OECD. (2014). OECD family database. Paris: OECD. www.oecd.org/social/family/database.htm Accessed 2 Sept 2015.

Prskawetz, A., Sobotka, T., Buber, I., Engelhardt, H., & Gisser, R. (2008). Austria: Persistent low fertility since the mid-1980s. Demographic Research, 19, 293–360. Special Collection 7: Childbearing trends and policies in Europe childbearing trends and policies in Europe. http://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol19/12/19-12.pdf Accessed 7 Sept 2015.

Sauvain-Dugerdil, C. (2005). La place de l’enfant dans les projets de vie. In J.-M. Le Goff, C. Sauvain-Dugerdil, C. Rossier, & J. Coenen-Huther (Eds.), Maternité et parcours de vie: L’enfant a-t-il toujours une place dans les projets des femmes en Suisse? (pp. 281–316). Berne: Peter Lang.

Skirbekk, V. (2008). Fertility trends by social status. Demographic Research, 18, 145–180. http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol18/5/18-5.pdf Accessed 19 Oct 2016

Sobotka, T. (2011). Fertility in Austria, Germany and Switzerland: Is there a common pattern? Comparative Population Studies, 36, 263–304.

Sobotka, T., & Beaujouan, E. (2014). Two Is best? The persistence of a two‐child family ideal in Europe. Population and Development Review, 40, 391–419.

Statistics Austria. (2013a). Kindertagesheimstatistik 2012/13. Vienna: Statistics Austria.

Statistics Austria. (2013b). Bevölkerungsstand 1.1.2013.. Vienna: Statistics Austria.

Viazzo, P. P. (1989). Upland communities: Environment, population and social structure in the Alps since the sixteenth century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wanner, P. (2000). L’organisation spatiale de la fécondité dans les agglomerations. Le cas de la Suisse, 1989–1992. Geographica Helvetica, 55, 238–250.

Wood, J., Neels, K., & Kil, T. (2014). The educational gradient of childlessness and cohort parity progression in 14 low fertility countries. Demographic Research, 31, 1365–1416. http://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol31/46/31-46.pdf Accessed 19 Oct 2016

Zeman, K. (2011). Human fertility database documentation: Austria. Human Fertility Database.

Zeman, K., Brzozowska, Z., Sobotka, T., Beaujouan, E., & Matysiak, A. (2014). Cohort fertility and education database. Methods Protocol. Available at www.cfe-database.org Accessed 18 Feb 2015.

Acknowledgements

This paper uses data collected in the Swiss Household Panel (SHP), based at the Swiss Centre of Expertise in the Social Sciences FORS, University of Lausanne. The SHP is financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation. The Families and Generations Survey (FGS) was carried out by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (SFSO). Funding for the supply of the Swiss Census data of 2000 and the FGS data from the SFSO was provided by the Institut de sciences sociales des religions contemporaines, University of Lausanne.

Zeman’s contribution to this chapter was funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the EU’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013)/ERC Grant agreement no. 284238. The data for Vienna from the Census of 2001 were obtained through the WIREL project on “Past, present and future religious prospects in Vienna 1950–2050” funded by WWTF, the Vienna and Science Technology Fund (2010 Diversity-Identity Call).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Burkimsher, M., Zeman, K. (2017). Childlessness in Switzerland and Austria. In: Kreyenfeld, M., Konietzka, D. (eds) Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, Causes, and Consequences. Demographic Research Monographs. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44667-7_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44667-7_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-44665-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-44667-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)