Abstract

Even though the average age at first childbirth has been increasing and education and employment options for women have improved immensely in recent decades, in France, unlike in other European countries, these developments have not led to a major increase in childlessness. Birth rates remain high and the share of the population who are childless is among the lowest in western Europe. This article discusses the historical roots as well as the societal conditions, institutional regulations, and political decisions that may explain the low levels of childlessness in France. We also discuss differences in rates of childlessness by education and occupation. Using a large representative survey on family life that was conducted parallel to the French census in 2011, we study the fertility histories of men and women born between the 1920s and late 1970s. We find that while the differences in fertility by level of education seem to have declined, having a higher education is still an obstacle to parenthood for women. For men, having a low educational and occupational status is associated with a greater likelihood of being childless. A large part of the differences in rates of childlessness between social groups can be traced back to the men and women who have never lived in a couple relationship; thus, partnership status can be regarded as a decisive parameter of the extent of childlessness.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Current discussions on decreasing birth rates, high rates of childlessness, and a lack of support for working parents in some European countries often cite France as an example of a country with a successful family policy. Compared with most other western European countries, France not only has higher maternal labour force participation rates; it also has higher fertility rates. As the average French woman has two children, the birth rate in France is higher than in any other European country, except for Iceland and Ireland (Eurostat 2012a). Less than 15 % of women in France remain childless; a share which is considerably lower than those of women in neighbouring countries like England, Switzerland, or Germany. In this article, we will attempt to explain why parenthood is still a standard part of the biography among French men and women. After providing an overview of the institutional regulations and family policies, we will present the most important demographic indicators of childlessness, and look at how they differ by social group.

2 Institutional Framework and Family Policies

When seeking to explain the high fertility rates and comparatively low childlessness rates in France, scholars often cite the country’s extensive and well-developed child care system and generous family benefit system, which provide tax deductions and financial support to families with many children (Ehmann 1997; Becker 2000; Fagnani 2002; Letablier 2002; Köppen 2006; Thévenon and Luci 2012). These high levels of state support and family-friendly measures can be traced back in history. France experienced a rapid drop in fertility much earlier than most countries, as birth rates were falling even in the nineteenth century. French women born in the middle of the nineteenth century had an average of 3.4 children. During the same period, women in France’ neighbouring country Germany had an average of 5.4 births, which was higher than the European average (Festy 1979: 49). Since then family policy in France has always had strong pro-natalistic elements. Even today, this bias is apparent in the promotion of large families and the relative neglect of one-child families in French family policy (Schultheis 1988: 92).

Some contemporary family benefits in France can also be traced back to charity programmes of Catholic enterprises during the nineteenth century: for example, child allowances, support of proprietary, and the work-free family Sunday evolved from voluntary benefits offered by employers (Spieß 2004: 51). During this period, so-called compensation funds were established to compensate wage earners for the burdens associated with rearing and caring for children. After employees went to court and demanded that these initially voluntary benefits were made mandatory in work contracts, the benefits became a standard part of regular wage employment, and these programmes increasingly came under state control. First, family compensation funds, which took over the payment of family benefits from companies, were founded in 1920. A large proportion of employees had to join these funds in 1932. In response to the on-going decline in the population, the Code de la Famille standardised and regulated the hitherto non-governmental, corporate-based family policy in 1939. Today, family benefits are organised and financed through the Caisse Nationale d’Allocation Familiale (CNAF), the bureaus in charge of distributing family benefits. One-third of the funding of the CNAF comes from the government, and two-thirds comes from employer contributions and tobacco tax proceeds (Spieß 2004).

Another factor that helps to explain contemporary family policies in France is French laicism. The state in France has a strong legal mandate to intervene and participate in family matters and childcare arrangements. In particular, childcare is supported and subsidised by the state. There are historical reasons for this high degree of government involvement in family arrangements. To attenuate the influence of the Catholic Church on family and education and to ensure that children were raised as loyal republican citizens, the French government took over control of the educational system in the late nineteenth century. In 1881 a public educational system based on republican-secularist principles was established in France (Veil 2002: 1). As children are seen in France as the “future of the nation” (Letablier 2002: 171), the state is considered responsible for their well-being, health, and education. The government aims to provide equal opportunities to all children, regardless of their parents’ income. The principle that childcare should be state-supported is also based in moral concepts regarding the relationship between state and church. The church lobbied for Catholic and conservative values, whereas the state advocated republican values: i.e., the principles of égalité et liberté. To ensure that women do not have to leave the labour market when they become mothers, the state supports them by providing adequate childcare (Letablier 2002).

Having children is not seen as a reason for quitting work or reducing work hours. Although attendance is not obligatory, currently almost all French children between the ages of three and six attend preschool, the écoles maternelles. Thus, preschool is an established institution in France. The majority of children attend preschool between 8.30 a.m. and 4.30 p.m., and some preschools offer care after those hours (the so-called garderie). Most of the écoles maternelles are state-run and free of charge; however, parents have to pay a small amount for lunch and care after the official closing time (Letablier 2002: 172). In addition to public services, there are other forms of childcare in France. Childcare for children younger than 3 years of age is especially diverse, and is dominated by privately organised domestic childcare arrangements. The government provides financial allowances and tax deductions that offset the costs of employing a registered day-care professional (assistante maternelle agree). These benefits are available for dual-earner parents with children under 6 years of age who employ a registered day-care professional. Parents can also engage a nanny (nourrice), who may perform household work in addition to providing childcare. In this case as well, parents can apply for governmental assistance and make use of tax deductions (Becker 2000: 231f.). Children in compulsory education in France attend school all day. School starts at 8.30 a.m. and usually finishes at 4.00 or 4.30 p.m., interrupted by a break for lunch, which is paid for in part by the parents. Children in pre- or primary schools may attend after-school care programmes. However, as there is no school on Wednesday afternoons, parents may be forced to find alternative childcare arrangements, work part-time, or use the 35-h limit on working hours in France to take a half-day off on Wednesdays.

The cost of childrearing is reduced in France and parents are encouraged to return to work soon after giving birth not just by a comprehensive system of childcare, but also by a system of monetary benefits for families. In France, monetary incentives to remain home after the birth of the first child are comparatively low. Child benefits and paid parental leave have long been available to two-child families only. Before 1994, only families with at least three children were eligible for these allowances. However, since 2004 parents with one child also receive a basic allowance for the first 3 years and paid parental leave.

In France, under the principle of family splitting, the family’s tax burden is reduced based on the number of children. In this system families with at least three children and high-income households have the highest level of tax relief (Dingeldey 2000: 76). Thus, large families with dual-earner parents benefit the most from tax deductions.

This historically evolved system of comprehensive and reasonably priced childcare, lower taxes for large families, and high levels of acceptance of and appreciation for children in French society are among the reasons why France has relatively high birth rates, but also high levels of labour market attachment among women, and among mothers in particular. The dilemma of how to combine work and family that many women still have to face is thus less pronounced in France, but also the social pressure to have children is stronger in France than in most other western European countries (Debest and Mazuy 2014).

3 Female Employment

In recent decades the share of women who have a high level of education has been increasing in Europe. At the same time, female employment rates have been rising continuously. Table 4.1 displays the development of maternal employment in France for the years 1990, 1995, 2000, and 2013. Labour force participation rates increased steadily over this period, even among mothers with three and more children. In 2000 there is a noticeable decline in the rate of employment among mothers with two children, including those with one child under age three. This decrease has been attributed to changing parental leave regulations. Since 1994 women who gave birth to a second child could apply for paid parental leave. Before this point, only women with at least three children were eligible for paid leave. Younger and less educated women in particular took advantage of the paid leave option, and one-third of the applicants have been unemployed (Reuter 2002: 19).

The abovementioned changes in parental leave were apparently introduced to encourage women to withdraw from the labour market, at least for the years immediately after the birth of their second child (Reuter 2002: 19). In this context, another aspect worth mentioning is the high unemployment rate among French women. Unemployment is higher among women than among men, even though women are more likely to work in the public sector, which tends to be less affected than other sectors by unemployment (Toulemon and de Guibert-Lantoine 1998: 4). Young women in particular are at risk of becoming unemployed. In 2010, 23.7 % of all French women younger than age 25 were unemployed (Mansuy and Wolff 2012). In contrast, the unemployment rate of this particular group of women in Germany (eastern and western Germany combined) was just 8.8 % (Federal Statistical Office of Germany 2012).

However, in France a comparatively large share of women are in full-time employment. During the first half of the 1990s, less than 25 % of French women worked part-time, and almost 30 % of these women would have preferred to work full-time if given the choice. Recently, female part-time employment rates have increased slightly in France, but they are still lower than those in many other European countries (Eurostat 2012b).

4 Fertility and Ideal Family Size

As in most western European countries, a rather traditional view of family life dominated in French society until the 1970s: a family consisted of a male breadwinner who had to provide for his wife and at least three children. Since the beginning of the 1980s, alternative forms of private living arrangements have become increasingly important, and non-marital unions with children have become a permanent feature of everyday life. Almost 58 % of all children born in the year 2014 had non-married parents. In this respect, France and Scandinavia are quite similar: i.e., becoming a parent is no longer automatically associated with marriage.

France has one of the highest birth rates in Europe. Since 1975 the total fertility rate has been rather stable, at an average of 1.8 children per woman, and recent numbers indicate that the TFR has risen to two children per woman (Fig. 4.1). Even from a cohort perspective, French fertility is exceptionally high. For French women born in 1960, the cohort fertility rate is 2.1, which is basically replacement-level fertility (Mazuy et al. 2014). Moreover, childbearing intentions, as reported in social science surveys, are comparatively high in France. When people are asked about their ideal number of children, the scores are highest in France, Ireland, Finland, and Great Britain (Toulemon and Leridon 1999; Goldstein et al. 2003). In France, most men and women say two or three is the ideal number of children, and the average preferred family size is 2.6. Less than 5 % of French respondents see childlessness as the most favourable living arrangement (Toulemon 2001b). By contrast, the ideal family size in Germany is below two; the lowest number in Europe (Dorbritz and Ruckdeschel 2012).

5 Childlessness

5.1 How Is Childlessness Measured in France?

Three sources are available to estimate childlessness in France: the census, official registration, and survey data. We encounter certain problems when seeking to measure childlessness in France. The registration office in France does not register the births by their biological order (Toulemon 2001a). Therefore, vital statistics data do not provide information on the evolution of childlessness. Yet it is possible to get comparatively reliable information on the development of childlessness for France. Since 1982 the National Institute for Statistic and Economics Studies (INSEE) has conducted a series of surveys on family life in which 1–2 % of all women in France are interviewed. These women are also asked about their number of births. On the basis of these surveys it is possible to estimate the complete fertility histories of women born during the twentieth century. However, reliable information about the final number and order of births can be obtained only for women aged 45 and older, and with a small degree of uncertainty for women above age 40. For cohorts born after 1975 only estimations can be made, since they have not yet completed their fertility. In addition to these surveys, a yearly census has been conducted in France since 2004. Previously, census data had been collected every 8–9 years, and the last census year was 1999. Due to the survey structure of the census (a rolling system in which only part of the population are interviewed each year), the initial results were published in 2008, and have since been updated each year.

For most of the following analyses, we use the enquête Famille et logements, a representative survey on family life which has been conducted parallel to the 2011 census, and contains life histories of around 360,000 men and women. For the period estimates of mean age at first child birth, we used combined information from the 1999 family survey, the civil registration system, and the French census.

5.2 Development of Childlessness

In a first step, we display the mean age at first childbirth as an indicator of the postponement in childbearing. Subsequently, the focus will be on the development of childlessness in France.

When we look at the mean age at which women became mothers for the first time, we can clearly see a postponement to higher ages: the mean age at first childbirth increased from 24 years in the 1970s to 27.7 years in 1998 and to 28.1 years in 2010 (Table 4.2). Despite this shift to having children at older ages, the postponement of childbirth has not been associated with increasing shares of childlessness: 11–13 % of all women born 1960 in France remained childless (Toulemon and Mazuy 2001; Masson 2013). France not only holds a top position in overall fertility; it also has the lowest share of childlessness in western Europe.

Figure 4.2 displays the development of family size according to a fertility projection (Toulemon and Mazuy 2001). This projection is based on the 1999 family survey, and is updated here using the 2011 estimates.Footnote 1 For women born between 1935 and 1955, childlessness stabilises at around 12 % (11 % for cohorts around 1945). A slight increase can be observed for women born after 1960, and the proportion childless increases to 15 % among women born in 1980. The majority of women in France have at least two children. Starting with the 1930 cohort, the share of women with large families (four or more children) has been decreasing, and the share with two children has been increasing. However, smaller shares of women born after 1960 had only one child than had three children. The high number of three-child families can most likely be explained by French policies that support large families.

Number of children, women in France, birth cohorts 1920–1960, in per cent (Source: INSEE, enquêtes Étude de l’Histoire Familiale 1999 and Famille et logements 2011; Toulemon and Mazuy (2001) and authors’ update)

Figure 4.3 displays the shares of women who are childless by birth cohort and age. Due to the lack of men after the First World War (Onnen-Isemann 2003), almost one-quarter of the women born at the beginning of the twentieth century remained childless. Childlessness decreased to constant and stable low levels in the following cohorts, and started to increase again among women born after 1960. However, reliable numbers for the final shares of women who are childless cannot be estimated since not all women born during the 1970s had reached the end of their reproductive life in 2011. Nonetheless, it appears that rates of childlessness are lower in France than in most European countries, and that the increase in childlessness has slowed due to the increase in fertility in the 2000s (Toulemon et al. 2008).

5.3 Differences in Childlessness by Education and Occupation of Women

The transition to parenthood differs by education. Compared to women with higher levels of education, less educated women become mothers earlier and more frequently. Women with less education also have a high probability of having a child in a first union, whereas highly educated women are more likely to have a child in the second or third partnership episode. Lone parenthood after first childbirth is also more common among less educated women. The higher the level of education, the longer the duration of the partnership is likely to be before the birth of the first child (Mazuy 2006). As in other countries, women with a university degree are most likely to be childless.Footnote 2 The high proportion of university graduates who are childless is not a novelty, as highly educated women who were born before World War II also had high rates of childlessness (Fig. 4.4a). The exceptionally high rates of childlessness among highly educated women are partly attributable to their tendency to have their first child at a higher age, but also to the amount of time they live without a partner. These women tend to be older at their first union, and are more likely than less educated women to remain single (Robert-Bobée and Mazuy 2005; Masson 2013). In the more recent cohorts, women with low levels of education have higher rates of childlessness than women with short secondary education. This appears to be because the least educated make up a growing proportion of the women who never enter a union.

Proportion of childless women in France by level of education (in per cent), birth cohorts 1928–77 (Source: INSEE, enquête Famille et logements (2011), own estimations). Among cohorts born after 1972 (under age 38 at 1-1-2011), the proportions childless or who never lived in a union may decline after the survey

If we only consider women who are living or have ever lived as a couple, the degree of childlessness decreases for all women, regardless of the level of education. However, the proportion of childlessness is still higher for women with a university degree (Fig. 4.4b). The data for the cohorts born in 1973–1977, who were aged 33–37 at the time of the survey, are still provisional, especially for more educated women, who may have a first child after the survey.

Childlessness varies not only by level of education, but also by occupation. White-collar employees are more likely to remain childless than blue-collar workers, self-employed women, or women who have never been in employment. The lowest level of childlessness is observed among women who have never been employed or who work as farmers (Fig. 4.5). Again, the overall share of women who are childless decreases when we exclude women who have never been in a union (Fig. 4.6). But although the relative differences in childlessness between the single occupational groups become smaller when only women who ever lived as a couple are considered, the rates of childlessness are still higher among women in higher-level occupations than among women with a lower occupational status.

5.4 Men and Childlessness

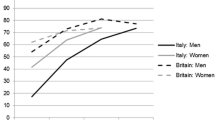

When we try to interpret permanent childlessness among men, certain problems arise. Whereas births can almost always directly be assigned to the respective mother, this is not always the case for men. Around 2 % of all children are not recognized by their biological father. On the basis of survey data, this results in an overestimation of biological childlessness for men (Toulemon and Lapierre-Adamcyk 2000). In addition, our analyses confirm that men tend to be older than women at first childbirth. Moreover, after a union disruption men may lose touch with their children, and may then become reluctant to refer to them in the survey, especially if they have almost never lived with their children or have no contact with them. Almost 60 % of women born around 1945 have been mothers at age 25, but only 40 % of men had a first child at this age (Fig. 4.7). The gender differences are estimated at around 2 % for the birth cohorts 1930–1945, and increase for younger cohorts.

Another reason for gender differences in childlessness are imbalanced partner markets, in which either men or women are overrepresented. Men born in France after 1940 remained childless to the same extent as women if they had ever lived as a couple. However, single men displayed a much higher rate of childlessness. A major reason for this pattern may be gender-specific immigration patterns. In the past, more men than women migrated to France, resulting in an excess of male marriage partners of reproductive ages. Among cohorts born after 1955, migration by sex is more balanced. Nevertheless, more men than women remain single (whereby more men than women experience many unions), which in turn leads to higher rates of childlessness among men. Moreover, union disruptions are more frequent among men, and some men lose touch with their children (Toulemon 1996: 8).

Among men, the effect of education on childlessness is the opposite of that among women. Like for women, the data for the cohorts born in 1973–1977 are still provisional. There are almost no differences in the levels of childlessness by education, except among men with a low level of education, who tend to be more likely to remain childless (Fig. 4.8). If men who have never lived in a couple relationship are excluded, less qualified men are as likely as better educated men to become fathers (Fig. 4.9). The high proportion of men with a low level of education who are childless is mainly due to their partnership status. They are more likely to be excluded from the marriage market, which hampers their chances of starting a family; while the opposite used to be the case for less educated women (Toulemon and Lapierre-Adamcyk 2000; Mazuy 2002). Over time, social differences based on the level of education are decreasing more rapidly among men than among women. Among recent cohorts, women with a low level of education have reduced risks of entering a union, and, as a consequence, are more likely to remain childless than women with secondary or tertiary education (Fig. 4.4a, Toulemon 2014). This trend is related to the increasing proportion of couples in which the woman is more educated than the man; a trend that has been observed in many countries around the world (Esteve et al. 2012). As it has become increasingly necessary to have two incomes to maintain a household, women with only a basic level of education and comparatively bad income prospects have lower chances of finding a suitable partner and eventually becoming a mother.

Proportion of childless men in France by level of education, birth cohorts 1928–1977 (Source: INSEE, enquête Famille et logements (2011), own estimations). Among cohorts born after 1972 (aged less than 38 years at 1-1-2011), the proportions childless or who never lived in a union may decline after the survey

There are marked differences in the levels of childlessness of different occupational groups. The higher a man’s occupational status, the less likely he is to remain childlessFootnote 3 (Fig. 4.10). Men who are farmers, blue-collar workers, or low-level white collar workers are more likely to remain childless than men who are self-employed or who work in higher-level white-collar occupations. In recent cohorts, childlessness has increased in all of the groups except for farmers, as this group is getting smaller, more selected, and more educated (a secondary diploma is now required to get the necessary loans for farming). While in the past a large share of farmers remained unmarried, this is no longer the case among recent cohorts. The differences between the various occupation groups have become smaller and the share of men who are childless has decreased, if only the men who have ever lived as a couple are considered (Fig. 4.11). Thus, it is again the elevated share of single men that contributes to the increase in childlessness in most occupational groups.

6 Conclusion

Our aim in this article was to present an overview of the development of childlessness in France, and to describe some of the underlying institutional trends. In western Europe, France has some of the smallest proportions of men and women who remain childless. When asked about their ideal number of children, only a very small share of French men and women say they do not want to have any children at all (Debest and Mazuy 2014). This is probably related to France’s system of state-supported family benefits and its well-developed childcare system. The French state and French society strongly promote and support the reconciliation of work and family life, but the social pressure to have children also remains strong.

However, the extent of childlessness differs between social groups: i.e., between birth cohorts, between men and women, and between different educational and occupational groups. For men and for women, childlessness is increasing in younger birth cohorts independent of their level of education or their occupational status. Whether this increase in childlessness is permanent or is due to a postponement of the first childbirth is not yet entirely clear. While the age at first birth in France has been increasing, birth rates have not been decreasing. Thus, it is possible that a non-negligible share of those men and women who are still childless at ages 35+ may still have children in the future.

One of the reasons why the childlessness rate is higher among men than among women is that problems arise when measuring the number of children men have. Imbalances in the partner market can also account for the higher rate of childlessness among men. Yet married men are as likely as married women to remain childless. Partnership status is thus a decisive parameter of the extent of childlessness. Men and women who have never lived in a couple relationship (either a marriage or a non-marital union) are much more likely to remain childless than those who live in or have lived in a union. Since more than 90 % of all men and women are or have been in a relationship, a large share of childlessness can be traced back to those 10 % who have been without a partner or remained single until the time of interview.

Despite the family-friendly conditions that help women combine work and family life, highly educated women in France are still more likely than less educated women to be childless, despite the fact that they now as likely to live in a couple relationship. During the period of life in which many women start a family, women who are earning a university degree are still in education or are trying to establish a career. The older they get, the more likely it is that their initial desire to have children, if any, will turn into involuntary childlessness due to infertility, or will be given up in favour of pursuing other goals. However, the differences by education are currently becoming smaller in France, mainly because the least educated women are more likely to remain childless.

In contrast, there are only slight differences in rates of childlessness by education among men. Men with low qualifications are more likely to remain single, and for that reason are also more likely than highly educated men to remain childless. This pattern can be observed for different occupational groups as well: blue-collar workers and low-level white-collar workers are the most likely to remain childless, as they are more likely than other occupational groups to have a precarious employment status or a low income. Among men in France, having an unstable economic situation leads to the postponement of marriage and family formation, which may result in childlessness (Oppenheimer 1988; Mills and Blossfeld 2003; Pailhé and Solaz 2012). Persistent high unemployment, an increase in the prevalence of part-time jobs, and the economic demand for dual-earner households may exacerbate feelings of economic uncertainty. This insecurity could lead young people to postpone childbearing, which may in turn lead to an increase in childlessness among younger cohorts.

Notes

- 1.

According to the 2011 survey, the proportion of women who are childless is higher than we would have predicted given the results of the 1999 EHF survey. In the 2011survey a minimum of 12 % is reached for cohorts 1935 and 1955, and infertility increases to 13 % for women born in 1960 and to 14 % for those born in 1965. However, based on the 1999 survey we assumed that the proportion childless would be as low as 10 % among the 1940–1960 cohorts. We believe that the 1999 survey partly overestimated cohort fertility due to a non-response bias (whereby childless women are more prone to avoid filling out a form). On the other hand, the data for the cohorts born before 1950 may become less reliable in 2011, when cohorts were 12 years older than in 1999, due to differential mortality and out-migration. We thus transformed our projection using the mean of both surveys estimates for the 1920 cohort, the 2011 estimate for the 1960 cohort, and similar assumptions on trends for more recent cohorts. For the sake of simplicity, we use the 2011 survey only when we compare subgroups within the population, as for older cohorts the social differences are similar.

- 2.

French levels of education are defined as follows: (1) Collège = first 4 years of secondary education from the ages of 11–15; 2. CAP-BEP = vocational high school after collège, duration 2–3 years; (3) Baccalauréat = baccalauréat diploma that leads to higher education studies or directly to professional life; (4) Sup = all higher education studies such as bachelor’s, master’s, or doctoral programmes.

- 3.

More than half of all men who have never been employed remain childless. Due to a strong selection of these men who have never worked and due to the very small sample size, we do not display them in the graph.

Literature

Avenel, M., & Roth, N. (2001). Les enfants moins de 6 ans et leurs familles en France métropolitaine. Recherches et Prévisions, 63, 91–97.

Becker, A. (2000). Mutterschaft im Wohlfahrtsstaat. Familienbezogene Sozialpolitik und die Erwerbsintegration von Frauen in Deutschland und Frankreich. Berlin: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin.

Bellamy, V., & Beaumel, C. (2015). Bilan démographique 2014. Des décès moins nombreux, Insee première, 1532, 4 pages. http://www.insee.fr/fr/themes/document.asp?reg_id=0&ref_id=ip1532. Accessed 30 Mar 2015.

Council of Europe. (2004). Recent demographic developments in Europe: Demographic Yearbook 2003. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Davie, E. (2012). Un premier enfant à 28 ans. INSEE Première 1419. Paris: INSEE. http://www.insee.fr/fr/ffc/ipweb/ip1419/ip1419.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2015.

Debest, C., Mazuy M., & Fecond Team. (2014) Childlessness: A life choice that goes against the norm. Population & Societies, 508, http://www.ined.fr/en/resources_documentation/publications/pop_soc/bdd/publication/1671/. Accessed 30 Mar 2015.

Dingeldey, I. (2000). Begünstigungen und Belastungen familialer Erwerbs- und Arbeitszeitmuster in Steuer- und Sozialversicherungssystemen. Ein Vergleich zehn europäischer Länder. Gelsenkirchen: Institut Arbeit und Technik.

Dorbritz, J., & Ruckdeschel, K. (2012). Kinderlosigkeit – differenzierte Analysen und europäische Vergleiche. In: D. Konietzka & M. Kreyenfeld (Eds.), Ein Leben ohne Kinder. Ausmaß, Strukturen und Ursachen von Kinderlosigkeit (pp. 253–278). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Ehmann, S. (1997). Familienpolitik in Frankreich und Deutschland: Ein Vergleich. Frankfurt/Main: Peter Lang.

Esteve, A., Garcia, J., & Permanyer, I. (2012). Union formation implications of the gender gap reversal in education: The end of hypergamy. Population and Development Review, 38, 535–546.

Eurostat. (2012a). Basic figures on the EU: Autumn 2012 editing. Luxemburg: Eurostat.

Eurostat. (2012b). Datenbank Beschäftigung und Arbeitslosigkeit: Teilzeitbeschäftigung als Prozentsatz der gesamten Beschäftigung, nach Geschlecht und Alter. Luxemburg: Eurostat.

Fagnani, J. (2002). Why do French women have more children than German women? Family policies and attitudes towards child care outside the home. Community, Work and Family, 5, 103–120.

Federal Statistical Office of Germany. (2012). Statistisches Jahrbuch (p. 356). Wiesbaden: Federal Statistical Office of Germany.

Festy, P. (1979). La Fécondité des pays occidentaux de 1870 à 1970. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, INED.

Goldstein, J., Lutz, W., & Testa, M. R. (2003). The emergence of sub-replacement family size ideals in Europe. Population Research and Policy Review, 22, 479–496.

Guggemos, F., & Vidalenc, J. (2014). Activité des couples selon l’âge quinquennal, le nombre et l’âge des enfants de moins de 18 ans. Paris: INSEE. http://www.insee.fr/fr/publications-et-services/irweb.asp?id=irsoceec12. Accessed 25 Mar 2015.

Köppen, K. (2006). Second births in western Germany and France. Demographic Research, 14, 295–330.

Letablier, M.-T. (2002). Kinderbetreuungspolitik in Frankreich und ihre Rechtfertigung. WSI Mitteilungen, 55, 169–175.

Mansuy, A., & Wolff, L. (2012). Une photographie du marché du travail en 2010, INSEE Première, 1391. Paris: INSEE. http://www.insee.fr/fr/ffc/ipweb/ip1391/ip1391.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2015.

Masson, L. (2013). Avez-vous eu des enfants ? Si oui, combien ? France Portrait social, 93–109. http://www.insee.fr/fr/themes/document.asp?reg_id=0&id=4062. Accessed 30 Mar 2015.

Mazuy, M. (2002). Situations familiales et fécondité selon le milieu social. Résultats à partir de l’enquête EHF de 1999. INED, Documents de travail n°114. https://www.ined.fr/fichier/s_rubrique/19428/114.fr.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2014.

Mazuy, M. (2006). Être prêt-e, être prêts ensemble? Entrée en parentalité des hommes et des femmes en France. Thèse de Doctorat en démographie, Université Paris 1.

Mazuy, M., Barbieri, M., & d’Albis, H. (2014). Recent demographic trends in France: The number of marriages continues to decrease. Population-E, 69, 273–322.

Mills, M., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (2003). Globalization, uncertainty and changes in early life courses. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 6, 188–218.

Onnen-Isemann, C. (2003). Familienpolitik und Fertilitätsunterschiede in Europa: Frankreich und Deutschland. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte Beilage zur Wochenzeitung Das Parlament B, 44(03), 31–38.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1988). A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 563–591.

Pailhé, A., & Solaz, A. (2012). The influence of employment uncertainty on childbearing in France: A tempo or quantum effect? Demographic Research, 26, 1–40.

Reuter, S. (2002). Frankreichs Wohlfahrtsstaatsregime im Wandel? Erwerbsintegration von Französinnen und familienpolitische Reformen der 90er Jahre. ZES-Arbeitspapier Nr. 12, Bremen: Zentrum für Sozialpolitik.

Richet-Mastain, L. (2006). Bilan démographique 2005, INSEE Première 1059. Paris: INSEE. http://www.insee.fr/fr/ffc/docs_ffc/IP1059.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2015.

Robert-Bobée, I., & Mazuy, M. (2005). Calendriers de constitution des familles et âge de fin des études. In: C. Lefevre & A. Filhon (Eds.), Histoires de familles, histoires familiales, Les Cahiers de l’Ined, 156, 175–200.

Schultheis, F. (1988). Familien und Politik. Formen wohlfahrtsstaatlicher Regulierung von Familie im deutsch-französischen Gesellschaftsvergleich. Konstanz: UVK.

Spieß, K. (2004). Parafiskalische Modelle zur Finanzierung familienpolitischer Leistungen. Berlin: DIW.

Thévenon, O., & Luci, A. (2012). Reconciling work, family and child outcomes: What implications for family support policies? Population Research and Policy Review, 31, 855–882.

Toulemon, L. (1996). Very few couples remain voluntarily childless. Population: An English Selection, 8, 1–28.

Toulemon, L. (2001a). How many children and how many siblings in France in the last century? Population and Societies, 374, Paris: INED. http://www.ined.fr/fichier/s_rubrique/173/pop_and_soc_english_374.en.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2015.

Toulemon, L. (2001b). Why fertility is not so low in France. Paper presented at the IUSSP seminar on International Perspectives on Low Fertility: Trends, Theories and Policies, Tokyo, 21–23 March 2001.

Toulemon, L. (2014), Single low-educated women and growing female hypogamy. A major change in the union formation process. 2014 Quetelet Seminar: 40th edition Fertility, childlessness and the family: A pluri-disciplinary approach. http://www.uclouvain.be/478889.html. Accessed 30 Mar 2015.

Toulemon, L., & de Guibert-Lantoine, C. (1998). Fertility and family surveys in countries of the ECE region. Standard country report France. New York: United Nations.

Toulemon, L., & Lapierre-Adamcyk, E. (2000). Demographic patterns of motherhood and fatherhood in France. In: C. Bledsoe, S. Lerner, & J. Guyer (Eds.), Fertility and the male life cycle in the era of fertility decline (pp. 293–330). Oxford: University Press.

Toulemon, L., & Leridon, H. (1999). La famille idéale: combien d’enfants, à quel âge? INSEE Première 652, Paris: INSEE. http://www.insee.fr/fr/ffc/docs_ffc/ip652.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2015.

Toulemon, L., & Mazuy, M. (2001). Les naissances sont retardées mais la fécondité est stable. Population, 56, 611–644.

Toulemon, L., Pailhé, A., & Rossier, C. (2008). France: High and stable fertility. Demographic Research, 19, 503–556. Special Collection 7: Childbearing Trends and Policies in Europe. http://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol19/16/. Accessed 30 Mar 2015.

Veil, M. (2002). Ganztagsschule mit Tradition: Frankreich. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, Beilage zur Wochenzeitung Das Parlament, B 41/02, 29–37.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Köppen, K., Mazuy, M., Toulemon, L. (2017). Childlessness in France. In: Kreyenfeld, M., Konietzka, D. (eds) Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, Causes, and Consequences. Demographic Research Monographs. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44667-7_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44667-7_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-44665-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-44667-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)