Published online Apr 18, 2014. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i2.146

Revised: December 29, 2013

Accepted: January 15, 2014

Published online: April 18, 2014

The painful sesamoid can be a chronic and disabling problem and isolating the cause can be far from straightforward. There are a number of forefoot pathologies that can present similarly to sesmoid pathologies and likewise identifying the particular cause of sesamoid pain can be challenging. Modern imaging techniques can be helpful. This article reviews the anatomy, development and morphological variability present in the sesamoids of the great toe. We review evidence on approach to history, diagnosis and investigation of sesamoid pain. Differential diagnoses and management strategies, including conservative and operative are outlined. Our recommendations are that early consideration of magnetic resonance imaging and discussion with a specialist musculoskeletal radiologist may help to identify a cause of pain accurately and quickly. Conservative measures should be first line in most cases. Where fracture and avascular necrosis can be ruled out, injection under fluoroscopic guidance may help to avoid operative intervention.

Core tip: This paper is a review article examining available evidence on the anatomy, function and common variation in the sesmoids of the great toe. There is discussion of the presentation, history, examination, investigations and subsequent management of the patient with a painful sesamoid. We discuss the role of operative intervention. We recommend early use of magnetic resonance imaging and discussion with a musculoskeletal radiologist to assist in diagnosis. Conservative management should be the first line in most cases.

- Citation: Sims AL, Kurup HV. Painful sesamoid of the great toe. World J Orthop 2014; 5(2): 146-150

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v5/i2/146.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v5.i2.146

The term sesamoid comes from the Arabic word, semsem, meaning sesame seed. Galen named these small rounded bones in reference to their similarity to sesame seeds[1]. The anatomic locations of some sesamoid bones are constant but others are variable.

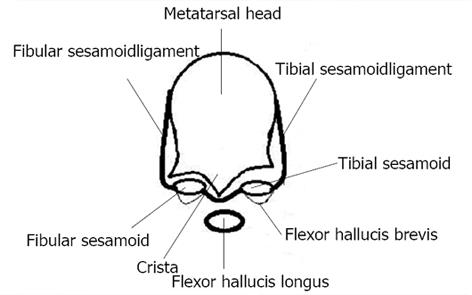

The two sesamoid bones of the big toe metatarsophalangeal joint are contained within the tendons of Flexor Hallucis Brevis and forms portion of the plantar plate. There are two sesamoids, tibial (medial) and fibular (lateral) sesamoids. The sesamoids articulate on their dorsal surface with the plantar facets of metatarsal head[2]. A crista or intersesamoid ridge separates the medial and lateral metatarsal facets. The crista provides intrinsic stability to the complex. In severe cases of hallux valgus the intersesamoid ridge atrophies and can be obliterated. The sesamoids are connected to the plantar aspect of proximal phalanx through plantar plate[3] which is continuation of the flexor hallucis brevis tendon[4]. The inferior surface of the sesamoid is covered by a thin layer of flexor hallucis brevis tendon and superior surface is articular. The sesamoids are suspended by a sling like mechanism; sesamoid ligaments to the corresponding aspect of metatarsal head (Figure 1). There is no direct connection between sesamoids and flexor hallucis longus tendon that runs between them. The abductor hallucis and adductor hallucis tendons have fibrous insertions into the tibial and fibular sesamoids respectively. The deep transverse metatarsal ligament attaches to the fibular sesamoid[5].

The function of sesamoids is to distribute weight bearing of first ray, increase mechanical advantage of the pull of short flexor tendon and stabilize the first ray. The tibial sesamoid normally assumes most of the weight bearing forces transmitted to the head of the first metatarsal[6]. When a person is in standing position sesamoids are proximal to the metatarsal heads. With dorsiflexion of first ray they however move distally thereby protecting the exposed plantar aspect of metatarsal head. When a person rises on to the toes, sesamoids (especially tibial) act as the main weight bearing focus for medial forefoot. Tibial sesamoid is more prone for pathology due to increased loading on this by the first metatarsal head[7].

Sesamoids have a tenuous blood supply and this is often variable as well. Blood supply to sesamoids enters mostly from proximal part and distal part has more tenuous blood supply. This can lead to delayed or unsuccessful healing following injury[8].

Sesamoids ossify between the ages of 6 and 7. Ossification of sesamoids often occurs from multiple centres and this is the reason for bipartite sesamoids. Bipartite sesamoids are a normal anatomical variant. Studies quote the incidence of bipartite sesamoids to be between 7 and 30[9-11]. Ninety percent involve tibial sesamoid and 80%-90% are bilateral[10]. Bipartite sesamoid has narrow and distinct regular edges and also are usually larger than single sesamoid. Some of these divided sesamoids do undergo osseous union with time. The synchondrosis between the sesamoid fragments can also disrupt with injury leading to symptoms and makes it difficult to distinguish whether some of these partite sesamoids are actually ununited fractures[12]. A Bone scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan may help in differentiating between the two[13]. Bipartite sesamoids can predispose to hallux valgus deformity as twice higher incidence is noted in patients with Hallux Valgus[14].

Other variations with sesamoids include congenital absence (reported widely in literature)[15-17] and also changes in shape. Hypertrophy can cause a projection on the plantar surface leading to hyperkeratotic lesion. Exostoses of sesamoids have been reported and these can cause keratosis or ulcerations. Hypertrophied fibular sesamoid can cause pain in the first intermetatarsal space due to local irritation or nerve compression. Coalition of sesamoids can also occur and give rise to symptoms (Figure 2)[18].

Pain is typically during toe off phase of gait. Careful history taking should include examination of footwear used in past and present, leisure activities to identify causation, occupation and treatment taken so far. Occupational factors include running, ballet dancing and jumping from a height[19-21]. The wearing of high heels and a high arched foot type also has an aetiological association. Previous injections to the area and smoking status should be asked for. Patients tend to avoid weight bearing on the involved sesamoid and load the lateral aspect of foot.

Findings include restricted and painful range of metatarsophalangeal joint motion, tenderness (Figure 3), and diminished plantar flexion strength. With long standing overloading, an intractable plantar keratotic lesion may develop beneath the affected sesamoid. Any tendency for hallux valgus, varus or clawing should be looked for. Examination of sensory nerves is important to rule out digital nerve compression[11].

Routine AP and lateral radiographs provide limited information. The tibial sesamoid can be better imaged with a medial oblique view and the fibular sesamoid can be visualised better with a lateral oblique view. An axial sesamoid view will provide a better profile of both sesamoids with their metatarsal articulations (Figure 4)[22].

Isotope bone scanning can demonstrate altered uptake before radiographs show changes. It shows increased uptake prior to development of radiological changes such as sclerosis, fragmentation. Bone scanning may be of use in differentiation of the fractured sesamoid from the congenital bipartite sesamoid[23].

Pathologies affecting the hallucal sesamoids may have overlap of both history and examination. For this reason, imaging is a useful tool that can differentiate causes of sesamoid pain where a diagnosis may not otherwise be easily made[20]. It can also distinguish between bipartite sesamoids and fracture non-unions. This is currently the investigation of choice for most sesamoid pathology[20,24].

Intractable plantar keratosis may form under the heads of the metatarsals. This can often be as a result of repeated abrasion or increased activity. It is important to differentiate IPK from verruca. Radiographs may help to identify causative osseous abnormality. This may include deformity of an underlying sesamoid. Management may involve activity modification, padding of pressure areas, use of orthosis or shaving of the keratosis. For persistent cases, condylectomy or osteotomy may be required[25].

Bursitis may affect the intermetatarsal bursae or the adventitial bursae. magnetic resonance imaging may help to diagnose the location of the affected bursa. Should conservative measures fail, bursectomy alone or in combination with sesamoidectomy or metatarsal osteotomy may provide relief[26].

Plantar medial and plantar lateral digital nerves travel near to the corresponding sesamoids and can be a source of pain. Nerve compression at these sites can cause altered sensation, pain and a positive Tinel’s sign. Surgical decompression may be indicated in the resistant case[5].

This may be associated with Hallux rigidus or localized to the sesamoid metatarsal articulation. This can develop secondary to trauma, chondromalacia or sesamoiditis. If conservative treatment fails where disease is restricted to one sesamoid resection of the involved sesamoid may help. When both sesamoids are involved excision can lead to clawing, hence MTP fusion is more appropriate[18].

Infection of sesamoids is uncommon. Direct trauma with puncture wound or breakdown of skin in those with peripheral neuropathy are the common mechanisms. Should antibiotic therapy prove ineffective, excision of the sesamoid can be considered. Care should be taken when excising the sesamoids to preserve the surrounding structures to prevent development of intrinsic minus deformity[11].

An acute fracture of unipartite sesamoid can be differentiated from a congenital bipartite sesamoid using bone scan or MRI. Bipartite sesamoids can also fracture following trauma when the synchondrosis between the two sesamoid fragments prevents healing. Rest in a non-weight bearing cast for 6 to 8 wk is the first line of treatment. Symptomatic non-union may be treated with percutaneous screw fixation, open fixation or open bone grafting (Figure 5)[27]. Surgical excision may be reserved for revision surgery.

As hallux valgus develops, first metatarsal drifts medially. The sesamoids maintain their relationship to the second metatarsal due to tethering by transverse metatarsal ligament and adductor hallucis tendon. There is often erosion of the crisita and increased weight bearing by the tibial sesamoid. Fibular sesamoid is spared as it is displaced into the first intermetatarsal space[28].

Sesamoids have a tenuous circulation making them vulnerable to avascular necrosis. In cases of avascular necrosis trauma may be an aetiological factor. Radiographs may show fragmentation with areas of increased bone density. MRI is also helpful in diagnosis. Excision of the sesamoid is reserved for cases where conservative management is ineffective[11].

Sesamoiditis is a diagnosis of exclusion once other causes of sesamoid pain have been excluded. Sesamoiditis is a painful condition affecting the sesamoids and can occur with or without trauma. This may be due to cartilage abnormalities similar to chondromalacia of patellofemoral joint[29] or inflammation of peritendinous structures. This condition is typically seen in younger women. The tibial sesamoid is more often involved. Radiographs are usually normal and bone scan and MRI may help in diagnosis. Conservative treatment involves decrease in activity. Low heels reduce pressure on sesamoids. Offloading custom made insoles are often helpful. Injections can be helpful and when everything fails excision is treatment of choice.

Initial attempts at management include a period of non- or reduced weight bearing, providing wide shoes with a reduced heel height, orthotics or padding[30]. The toes may be taped in plantar flexion or neutral to avoid excessive dorsi-flexion. Clinical evidence confirming resolution of symptoms with simple, conservative measures is often possible[31]. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may also help to provide relief.

Steroid and local anaesthetic injections can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. Injections are usually done under radiological guidance to improve accuracy of needle placement. Steroid injections should not be used in presence of a sesamoid fracture or avascular necrosis[3].

In the presence of an intractable plantar keratosis due to prominence of a tibial sesamoid, shaving of the plantar half of the sesamoid may provide relief without excision of the complete sesamoid. This should only be attempted in the presence of normal mobility at the first metatarsal[32].

Surgical excision of a sesamoid should be considered only when other treatment modalities have failed. Only one sesamoid may be excised, excision of both is likely to lead to a cock-up deformity or a claw toes deformity[30]. The sesamoid to be excised will dictate the surgical approach. For tibial sesamoidectomy a medial approach is preferred to avoid injury to plantar medial nerves. In one study, ninety-percent of patients were able to return to normal pre-morbid levels of activity following tibial sesamoidectomy[33]. A dorsolateral approach is preferred for fibular sesamoidectomy as a plantar approach is likely to encounter the neurovascular bundle and flexor hallucis longus tendon, making access difficult[11]. Painful plantar scar is a difficult problem to resolve and should be avoided.

In cases of fracture of the sesamoid unresponsive to conservative management, percutaneous fixation of the sesamoid may provide improvement of symptoms. In one study of nine patients managed this way, all patients had dramatic relief from pain at three months post-operatively[27].

A range of conditions can lead to sesamoid pain. Careful history examining occupation and hobbies alongside a thorough examination and use of appropriate imaging modalities are likely to identify aetiology. Our recommendations are that early consideration of MRI and discussion with a specialist musculoskeletal radiologist may help to identify a cause of pain accurately and quickly. Conservative measures should in most cases be first line. Where fracture and avascular necrosis can be ruled out, injection under fluoroscopic guidance may help to avoid operative intervention. Operative intervention used only in resistant cases operative morbidity should be considered and explained to patients.

P- Reviewers: Chen YK, Peng BG S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | van Dam Scott BE, Dye F, Wilbur Westin G. Etymology and the Orthopaedic Surgeon: Onomasticon (Vocabulary). Iowa Orthop J. 1991;11:84-90. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Aseyo D, Nathan H. Hallux sesamoid bones. Anatomical observations with special reference to osteoarthritis and hallux valgus. Int Orthop. 1984;8:67-73. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Deland JT, Lee KT, Sobel M, DiCarlo EF. Anatomy of the plantar plate and its attachments in the lesser metatarsal phalangeal joint. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:480-486. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Brenner E. The intersesamoidal ridge of the first metatarsal bone: anatomical basics and clinical considerations. Surg Radiol Anat. 2003;25:127-131. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Anwar R, Anjum SN, Nicholl JE. Sesamoids of the Foot. Curr Orthopaed. 2005;19:40-48. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Dedmond BT, Cory JW, McBryde A. The hallucal sesamoid complex. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:745-753. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Shereff MJ, Bejjani FJ, Kummer FJ. Kinematics of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:392-398. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Rath B, Notermans HP, Frank D, Walpert J, Deschner J, Luering CM, Koeck FX, Koebke J. Arterial anatomy of the hallucal sesamoids. Clin Anat. 2009;22:755-760. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Frankel JP, Harrington J. Symptomatic bipartite sesamoids. J Foot Surg. 1990;29:318-323. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Munuera PV, Domínguez G, Reina M, Trujillo P. Bipartite hallucal sesamoid bones: relationship with hallux valgus and metatarsal index. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36:1043-1050. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Richardson EG. Hallucal sesamoid pain: causes and surgical treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7:270-278. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Van Hal ME, Keene JS, Lange TA, Clancy WG. Stress fractures of the great toe sesamoids. Am J Sports Med. 1982;10:122-128. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Cohen BE. Hallux sesamoid disorders. Foot Ankle Clin. 2009;14:91-104. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Weil LS, Hill M. Bipartite tibial sesamoid and hallux abducto valgus deformity: a previously unreported correlation. J Foot Surg. 1992;31:104-111. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Day F, Jones PC, Gilbert CL. Congenital absence of the tibial sesamoid. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2002;92:153-154. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Jeng CL, Maurer A, Mizel MS. Congenital absence of the hallux fibular sesamoid: a case report and review of the literature. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:329-331. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Le Minor JM. Congenital absence of the lateral metatarso-phalangeal sesamoid bone of the human hallux: a case report. Surg Radiol Anat. 1999;21:225-227. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Coughlin MJ, Mann RA, Saltzman CL, Anderson RB. Surgery of the Foot and Ankle. St. Louis: Mosby 2007; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Hillier JC, Peace K, Hulme A, Healy JC. Pictorial review: MRI features of foot and ankle injuries in ballet dancers. Br J Radiol. 2004;77:532-537. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Karasick D, Schweitzer ME. Disorders of the hallux sesamoid complex: MR features. Skeletal Radiol. 1998;27:411-418. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | McBryde AM, Anderson RB. Sesamoid foot problems in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 1988;7:51-60. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Richardson EG. Injuries to the hallucal sesamoids in the athlete. Foot Ankle. 1987;7:229-244. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Maurice HD, Newman JH, Watt I. Bone scanning of the foot for unexplained pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:448-452. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Sanders TG, Rathur SK. Imaging of painful conditions of the hallucal sesamoid complex and plantar capsular structures of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Radiol Clin North Am. 2008;46:1079-1092, vii. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Coughlin MJ. Common causes of pain in the forefoot in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:781-790. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Ashman CJ, Klecker RJ, Yu JS. Forefoot pain involving the metatarsal region: differential diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiographics. 2001;21:1425-1440. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Blundell CM, Nicholson P, Blackney MW. Percutaneous screw fixation for fractures of the sesamoid bones of the hallux. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:1138-1141. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Bulstrode C, Wilson-Macdonald J, Fairbank J, Eastwood D. Oxford Textbook of Trauma and Orthopaedics. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2011; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Apley AG. Open sesamoid. A re-appraisal of the medial sesamoid of the hallux. Proc R Soc Med. 1966;59:120-121. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Leventen EO. Sesamoid disorders and treatment. An update. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;236-240. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Heim M, Siev-Ner Y, Nadvorna H, Marcovich C, Engelberg S, Azaria M. Metatarsal-Phalangeal Sesamoid Bones. Curr Orthopaed. 1997;11:267-270. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Mann RA, Wapner KL. Tibial sesamoid shaving for treatment of intractable plantar keratosis. Foot Ankle. 1992;13:196-198. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Lee S, James WC, Cohen BE, Davis WH, Anderson RB. Evaluation of hallux alignment and functional outcome after isolated tibial sesamoidectomy. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:803-809. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |