Dementia in People with a Turkish Migration Background: Experiences and Utilization of Healthcare Services

Abstract

Background:

As the proportion of older people with migration background (PwM) increases, the proportion of older PwM with dementia might also increase. Dementia is underdiagnosed in this group and a large proportion of PwM with dementia and family caregivers are not properly supported. Healthcare utilization is lower among older migrant populations. Thus, a better understanding of how PwM and family caregivers perceive their situation and how they experience healthcare services is needed to improve utilization of the healthcare system.

Objective:

Analyze how family caregivers of PwM with dementia experience their situation, why healthcare services are utilized less often, and what can be done to reverse this.

Methods:

Eight semi-structured interviews were conducted with people with Turkish migration background caring for PwM with dementia. Qualitative content analysis was used for data analysis.

Results:

Daily care was performed by one family member with the support of others. Healthcare services were used by most participants. Participants identified a need for better access to relevant information and incorporation of Turkish culture into healthcare services.

Conclusion:

PwM face similar challenges in taking care of persons with dementia as those without migration background. There is a willingness to use services, and services embracing Turkish culture would help to reduce hesitance and make affected people feel more comfortable, thereby increasing utilization and satisfaction. A limitation of this study is that participants were already connected to health services, which may not reflect the help-seeking behavior of those in the Turkish community who are not involved in healthcare.

INTRODUCTION

Germany, like many other European and western societies, faces increasing numbers of people with migration background (PwM) and health problems. The Federal Statistical Office of Germany defines migration background as not having German citizenship from birth or having at least one parent who does not have German citizenship from birth. This includes immigrant and nonimmigrant foreigners, immigrant and nonimmigrant naturalized citizens, German resettlers, and descendants born with German citizenship from the former groups [1]. According to census data, the number of PwM amounts to 18.6 million people, accounting for 23% of the population in Germany. In Germany, PwM often experience adverse health-related outcomes [2, 3]. However, they often do not utilize healthcare services to the same extent as those without a migration background, potentially exacerbating health related disparities in this population [2, 4, 5].

Older adults represent a subgroup of special interest in this population. According to census data, 1.99 million PwM are older than 64 years, representing 2.44% of the entire population of Germany and 11.52% of the population 65 years and older [1]. With increasing age, there is a growing probability of chronic and age-associated diseases including dementia [6, 7]. Dementia among people with migration background leads to different challenges for those affected as well as for professionals. For example, if the people affected have limited German language skills, it is problematic for them to communicate their symptoms to professionals; in turn, it is difficult for professionals to administer cognitive tests and interpret the results due to the lack of culturally sensitive cognitive tests and screening instruments, which may contribute to over- and underdiagnosis of dementia [8–11]. Provided both increasing numbers of persons with a migration background and growth in the older adult population and dementia cases, there is a need to better understand the specific problems facing this subpopulation and the healthcare system.

A major barrier to progress in this area is the lack of general research knowledge regarding people with migration background and dementia. For example, if more knowledge was available regarding their unique experiences with treatment and care directly from this population this would aid healthcare and service providers in tailoring their services to this population through more culturally responsive care. This is also critical to helping people with dementia and their family caregivers to engage support and resources to manage their situation. This is even more important when considering that PwM do not comprise one large homogeneous group where everyone with dementia can be treated the same. Similar to people without migration background, some characteristics are shared by some people but not others; thus, subgroups exist in this population and need to be identified. Recent analyses, for example, have highlighted the country of origin as a subgrouping factor. According to this estimation, approximately 96,500 PwM older than 64 years live with dementia in Germany. The most frequent migration backgrounds are as follows: Asian, Turkish, Polish, Russian, and Italian [12]. While there is little research focusing on Asian, Russian, or Italian countries of origin, there has been some research focusing on people from Turkey [13–16].

The number of people with Turkey as the country of origin in people 65 years and older is approximately 208,000, and the number of people with dementia in this group adds up to approximately 8,900 [12]. Thus, people from Turkey are not only one of the largest groups in the population of PwM in Germany but also in the group of PwM with dementia. Additionally, more research is needed on how to properly include PwM of Turkish background into the healthcare landscape. One previous study has identified challenges in treating and caring for this group. Based on personal interviews (n = 7) with people of Turkish background, the authors described that participants experienced a lack of knowledge about healthcare services and the fear of violating cultural norms when using professional help and formal services among others. Providing informal support is not guided by the diagnosis but rather that he or she needs help. These results are in line with other research in this field [13, 17, 18].

For the reasons cited above, we assume that dementia is even more underdiagnosed in PwM than in the population in Germany as a whole [19, 20]. This also results in a high unidentified proportion of family caregivers meaning a larger proportion of people in the group of PwM with dementia and their family caregivers are not being optimally supported by the healthcare system. In investigating how to optimally support this population, a practice-oriented approach is needed and it is important to analyze what is required in collaboration with the people affected. Generating such knowledge and using that approach could also help to ensure that cultural sensitivity will not be understood as a stereotyped concept but as a concept with different nuances that considers special characteristics without painting everyone with the same brush [18]. Considering the existing evidence, a need exists for action to determine the reasons for lower utilization of healthcare services and needed culturally responsive supports specific to dementia and caregiving. Due to a lack of culturally responsive healthcare services, it is important to determine what can be done to design healthcare services that are suitable for people with migration background, thereby increasing the utilization of healthcare services.

The present study focuses on PwM with dementia from Turkey and aims to: 1) examine the caregiving experience of family caregivers; 2) identify barriers to using information and healthcare services for people with dementia (PwD) by people with Turkish migration background; and 3) assess recommendations from the caregivers of PwM with dementia to increase healthcare utilization. The results are important to provide assistance to the healthcare system for a culturally sensitive approach in providing their healthcare services.

METHODS

The study was approved by the University Medicine Greifswald’s ethics committee. A qualitative design was chosen to obtain individual views on the topic of interest and in-depth responses on how participants experience caregiving, why they chose (or not) to utilize healthcare services, and what can be done to increase utilization [21]. The interviews were conducted in German, and quotes for this article were translated.

Participants

To be eligible for the study, the participants had to have a Turkish migration background and be involved in the care of a family member (also with a Turkish migration background) with dementia. Recruiting was performed via snowball sampling to obtain access to a population that is hard to reach [22, 23]. Stakeholders from the field of dementia and migration were contacted via phone or e-mail or at symposia and were asked to help find suitable interview partners. In doing so, Deutsche Alzheimer Gesellschaft, Demenz-Support Stuttgart, Demenz-Servicezentrum Gelsenkirchen, Landesverband der Alzheimer Gesellschaften NRW e. V. and freelance/self-employed individuals, among others, offering culture-specific services for the family members of PwD, were contacted. Additionally, two participants arranged contact for further interviews. The participants lived in North Rhine-Westphalia or Hessen and provided informed consent to participate in the study. The characteristics of the eight participants and their care situation can be found in Table 1.

Table 1

Characteristics of the participants and the care situation

| Participant | Age, sex | Who is cared for | Who is the main caregiver | Duration of caregiving | Living arrangement | Formal help or services |

| T1 | Female, 38 | Father | Brother of T1 | X | Father is living with brother of T1 | No |

| T2 | Female, 52 | Father | T2 | 1 y | Multigenerational house | No |

| T3 | Female, 57 | Father &mother | T3 | 13.5 y (3.5 y at T3’s home) | Father lived with T3 | Yes |

| Mother is living with T3 | ||||||

| T4 | Female, 52 | Mother | T4 | 8 y | Mother is living with T4 | Not anymore |

| T5 | Female, 31 | Grandmother | Mother of T5 | X | Grandmother is living with daughter (T4) | Not anymore |

| T6 | Female, 36 | Mother | Brother of T6 | X | Mother is living with brother of T6 | Yes |

| T7 | Female, 56 | Mother | Son of T7 | X | Mother is living on her own | Yes |

| T8 | Male, 49 | Mother | Wife of T8 | 4 y | Mother is living on her own | Yes |

The interview

The interviews followed a semi-structured question guide that covered a range of topics, including the care situation at home, the experience of caring, help from family and friends, the utilization of healthcare services, preferences regarding healthcare services, and differences in the healthcare systems between the country of origin and Germany (see Table 2).

Table 2

Question guide—examples

| Category | Question |

| Background | Can you tell me a bit about [person with dementia]? |

| What is your relationship to [person with dementia]? | |

| How long have you been caring for [person with dementia]? | |

| Before you started taking care of [person with dementia], did you have any other caregiving experience? | |

| Caregiving experience | How has it been caring for [person with dementia]? |

| What are the hardest things about caregiving for [person with dementia]? | |

| What are the most rewarding things about caregiving for [person with dementia]? | |

| Can you describe a time when you needed to get support or information to take care of [person with dementia]? | |

| Informal resources | Are other family members or friends involved in taking care of [person with dementia]? |

| What things make it difficult to involve family/friends in [person with dementia]’s care? | |

| Formal resources | Are there any services you are using to help with [person with dementia]’s care? |

| How did you find this service? | |

| How often do you use this service? | |

| How has this service been meeting [person with dementia] and your needs? | |

| What is working well with this service? | |

| What kinds of problems do you find with this service? | |

| Would you say your interactions with people from this service are generally positive or negative? | |

| How could this service be improved for people in the future? | |

| Differences in healthcare systems | What differences exist in the healthcare system between [country of origin] and Germany? |

| Are there dementia-specific healthcare services in [country of origin]? |

The question guide was developed in collaboration with the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where it has been applied in investigations of the needs of underserved dementia caregivers living in sociocontextually disadvantaged areas.

Data collection

To obtain data for this study, interviews with informal caregivers with a Turkish migration background were conducted. Despite a long recruiting phase and intensive attempts at recruiting, it was only possible to find n = 8 participants who were willing to be interviewed. The first author, a trained psychologist with acquired expertise in qualitative research, conducted the interviews, which occurred between June 2018 and March 2019 and lasted, on average, 72 minutes. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews followed a qualitative semi-structured question guide covering topics such as the care situation at home, utilization of healthcare services, inhibiting and supporting factors of this utilization, and preferences regarding healthcare services. For the interviews, an effort was made to make it as convenient as possible for the participants. It was offered to visit the interview partners at home or another place they wished, the participants could pick a weekday and time that suited them best, and, if desired, it was possible to have a translator present during the interview (either one of the stakeholders, or a family member, or a professional translator).

Analysis

The data were analyzed by the first author using qualitative content analysis [24]. A combination of deductive and inductive category formation was chosen to create the coding framework. Deductive categories were derived from the semi-structured question guide, and inductive subcategories emerged from the conducted interviews. Half of the interviews were utilized to identify additional subcategories that would be of interest for further analysis. These interviews were reviewed in their entirety and were performed more than once to ensure the coding framework will be encompassing. When no new categories could be derived from the interview material, the coding framework was used to interpret all the conducted interviews line-by-line.

RESULTS

The main findings of the interviews can be classified into five main categories: care situation, prior knowledge, challenges, utilization of healthcare services, and recommendations.

Care situation

The main care was usually provided by one family member. In this study, other family members, such as the husband, children, and neighbors, supported the main caregivers. The people involved in care considered it a matter of course that care was being handled within the family:

‘It is natural to me that I take care of my mom.’ (ref. T3, personal translation J. M.).

‘This is our mother, this is our father, we have to watch them. They have done so much for us, so we have to take care of them now.’ (ref. T4, personal translation J. M.).

The deciding factor in family care was that a family member needs help:

‘This is natural, also for my daughter.’ (ref. T3, personal translation J. M.).

This view was also shared by one interviewed grandchild:

‘Everybody has to help [ ... ] if this happens to my parents, I am not going to let other people take care of them. I will take care of them.’ (ref. T5, personal translation J. M.).

Most families reported having no previous experiences with dementia care and PwD. Participants perceived the care situation differently. For most, it was associated with challenges and stress, while one participant reported that taking care of a family member with dementia is fulfilling and being very thankful for the professional help she is getting:

‘... it is nice taking care of a family member. It is nicer than taking care of a stranger, isn’t it?’ (ref. T3, personal translation J. M.).

Prior knowledge

There was only very limited knowledge about dementia beforehand:

‘Like , only this online knowledge. What you can read on the internet, just that and nothing more.’ (ref. T1, personal translation J. M.).

‘I only knew that one forgets, forgets everything.’ (ref. T2, personal translation J. M.).

In some cases, this knowledge was not correct:

‘Alzheimer’s, they are forgetful [ ... ] and dementia is even more extreme.’ (ref. T6, personal translation J. M.).

There was no prior knowledge about information and healthcare services for PwD and their caregivers. The reason cited for this was that they did not experience dementia before so they did not occupy themselves with dementia and these kinds of services:

‘We experience these things for the first time. We don’t have someone in the family with it, so you don’t know that.’ (ref. T2, personal translation J. M.).

‘... maybe I don’t have so many friends, that are familiar with this.’ (ref. T1, personal translation J. M.).

Sources that were consulted to compensate these knowledge gaps were general practitioners, courses related to dementia, literature regarding dementia, people working in the field of dementia, health and nursing care insurance, and communication with other people in the same situation:

‘That is what I learned in the course. This did a lot for me and I won’t forget that.’ (ref. T2, personal translation J. M.),

‘We read a lot of specialized literature [ ... ] watched documentaries [ ... ] talked to people, who are working in that field.’ (ref. T5, personal translation J. M.).

Most of the participants were also very proactive in obtaining these information, e.g., calling institutions to learn what one can do, what services one can use, and what help is available:

‘I demand from the city. I always call someone. I go to the health insurance and the doctor.’ (ref. T2, personal translation J. M.).

‘I can talk to the doctor. I can coordinate very well with the doctors.’ (ref. T3, personal translation J. M.).

‘I called everyone. I searched for help.’ (ref. T3, personal translation J. M.).

Challenges

The main challenges reported were the aggressiveness of the family member with dementia, activity at night, forgetfulness, the need to watch the affected person at all times and to accept that the family member is changing:

‘She was a “power woman” and that [ ... ] she declined so much was hard to accept.’ (ref. T5, personal translation J. M.).

Not having time for oneself and the PwD running away and refusing to accept help were also challenges reported:

‘I don’t have time for myself or my children or my home.’ (ref. T8, personal translation J. M.),

‘I would like to, but my mother would never do that.’ (ref. T8, personal translation J. M.)

These situations led to several consequences for caregivers. The participants described physical as well as mental problems. They revealed experiencing stress, headaches and other physical pains, lack of sleep, desperation, exhaustion, a painful feeling due to the recognition of the irreversibility of the disease, depression, and constraints in personal life:

‘I took three years off because of my father [ ... ] and I haven’t gone anywhere [ ... ] it wasn’t possible with my father.’ (ref. T3, personal translation J. M.)

Caregivers also reported consequences for their livelihoods:

‘Until January he was working and now we closed our shop because we have to watch my mother.’ (ref. T4, personal translation J. M.)

Participants also described being hurt by comments made by the PwD.

However, there were also positive outcomes, such as developing the wish to care for other PwD in nursing homes or daycare facilities after their family member will be gone:

‘I could imagine myself working as a nurse in a daycare facility.’ (ref. T3, personal translation J. M.).

The participants developed several coping mechanisms to deal with their family member and his/her behavior. These were, for example, taking things lightly, explaining everything to the affected person, giving love, seeking help by professionals, treating the PwD like a child, reminding oneself that the family member has a disease:

‘She is ill, therefore I can’t be mad, it’s not her fault.’ (ref. T3, personal translation J. M.),

paying close attention to what the family member is doing at all times, being patient, and seemingly giving in to the wishes of the PwD.

Utilization of healthcare services

There was a general willingness to utilize healthcare services, and more than half of the participants are or were using these services, e.g., daycare, prevention care, dementia workshops, nursing service, intercultural “dementia guides,” and Turkish dementia cafés. However, reasons for not utilizing these services were a lack of knowledge (regarding culture-specific services as well as nonculture-specific services) and not being properly educated about services:

‘There is a pamphlet and other stuff, but if no one explains you everything and if you have never experienced it, then you just don’t know. Nobody tells you exactly how it’s done and then you don’t know.’ (ref. T2, personal translation J. M.),

a lack of available places in the care services:

‘Right now I don’t, because there is no place.’ (ref. T2, personal translation J. M.),

difficulty obtaining information about the services, worry about shortage of monetary reimbursement, and fear of what other people might think about someone using these services.

The fact that the PwD would refuse to use services was also mentioned:

‘I wanted care, help from the health insurance, but my father would never [ ... ] He would never get showered by a nurse.’ (ref. T2, personal translation J. M.).

The option of a nursing home for the PwD was rigorously refused by participants. Participants cited tradition of giving back to parents what parents gave to them:

‘Always giving back. That is our tradition. What you got, you want to give back.’ (ref. T3, personal translation J. M.)

Participants also noted it is shameful to transfer the parents to a nursing home because it would mean that the parents did not raise their children well and that the children are uncaring:

‘It is a shame, if you are put into a nursing home, then this person doesn’t have good children, they don’t have a good heart, they aren’t well-raised people.’ (ref. T3, personal translation J. M.).

‘This is our tradition, our culture, 99% of Turkish people think like that.’ (ref. T3, personal translation J. M.).

The fear of what other people might think is also a major factor of hindering service utilization:

‘Well, what would others think? [ ... ] my brother didn’t want to, for him it is still, others would think that the children left the mother alone.’ (ref. T6, personal translation J. M.).

Recommendations

Participants generally would like to use healthcare services, and most are or were using services. They also voiced limitations in existing services and noted room for improvement but were not sure how services could best be improved. However, participants offered several suggestions regarding dementia and healthcare services, which can be divided into two areas. One area is information. The participants wished for an easier way to obtain information about dementia, the healthcare system and healthcare services—for example, through culture-specific consultants who are employed by health and nursing care insurance. These consultants could visit the PwD at home and provide personalized/contextualized recommendations about what can be done in each individual’s situation. Furthermore, information should already be distributed to people at a younger age, e.g., by teaching dementia courses in schools.

The second area concerns the healthcare services themselves. Considering the rising numbers of PwM, the participants would like healthcare services to be more culture-specific so potential users could identify with them and feel enabled to engage:

‘Well, I think it is important, so that they can identify themselves with it [ ... ] that’s why it is important that there are services that consider the culture or language. So one feels more understood, also as a family member.’ (ref. T5, personal translation J. M.).

A big help in achieving this would be employment of staff with a Turkish migration background at healthcare institutions because language is an important aspect of culture and connection. PwM with dementia forget their German language skills, and it is easier for them and their family members to express what they are meaning and (especially) feeling in Turkish.

‘... same language would be important, although my grandmother can speak German [ ... ] but not in a way that she can express emotions ... ’ (ref. T5, personal translation J. M.).

DISCUSSION

The primary goals of this study were to depict the experiences of caregivers of people with dementia and a Turkish migration background, determine the reasons for the lower utilization of healthcare services by people with a Turkish migration background diagnosed with dementia and their family, and assess what can be done to reverse this circumstance from their point of view.

Our analyses revealed that PwM face similar challenges in taking care of PwD as people without migration background, e.g., difficulties with increased night activity, aggressiveness, the need to be alert at all times, and being stressed or facing job constraints [25–27]. To deal with these challenges, different coping mechanisms and measures are undertaken, e.g., reminding oneself that dementia is a disease and the PwD is not at fault, explaining everything to the PwD, and being patient with him/her.

Importantly, when the present participants were asked what they would like to have regarding services and if they wanted culture-specific services, most did not wish for services that are solely for people with a Turkish migration background. Instead, participants requested that existing services are more open to Turkish culture. Most Turkish participants experienced pronounced difficulties in obtaining information and/or a lack of information. One participant complained about not getting help and having to inform herself about everything related to dementia. Therefore, it seems to be a challenge to disseminate existing information to people with a Turkish migration background. These findings are in line with the “Allianz für Menschen mit Demenz” that illustrated the need for an approach that is specifically tailored to the needs of PwM concerning support services for PwM in their report. It is important to consider the differences in traditions, language, religion, and customs when taking care of this population [28, 29]. An example of this approach is “Diversity Management.” In the German healthcare system, a culturally sensitive and appropriate needs-based care is scarce; therefore, specific information about PwM cannot be fully considered. However, demographic and socioeconomic factors also play roles in the healthcare of PwM and should not be neglected. In optimizing care for PwM, diversity management suggests frameworks that should be implemented in the facilities of healthcare that not only allows for culturally sensitive responses to the needs of PwM but also promotes an open approach toward PwM [30].

As recommended by participants, to gain knowledge not only about available services but also other helpful measures, it would be useful to employ a consultant with a Turkish migration background to visit PwD and families at home. The consultant could take a close look at the situation and provide recommendations, serving as a navigator for healthcare utilization and other services. In connecting people of Turkish background to pertinent information, personal contact is important and desired. Additionally, the contact person must be someone who has good knowledge of Turkish culture because this helps people open up and feel understood; preferably, the contact perhaps also speaks Turkish as it is sometimes easier to share emotions in one’s native language. One illustration of the importance of being familiar with culture in the present study is the observation that nursing homes were not considered an option. The participants talked about how that is something that is just not done in Turkish culture because it means parents have not raised their children well, further supporting results by Mogar and von Kutzleben [13] suggesting that taking care of a family member is a matter of course and the deciding factor is that a family member needs help. This type of culture-specific information is important in forming trustworthy connections between consultants and the people of Turkish background looking for services.

It was evident that information on healthcare services is difficult to obtain and should be made easier for the people affected; another option would be to spread information about services where people with migration background are spending time, e.g., culture-specific community centers or mosques. To accomplish this, it is important to cooperate with people working there to spread the information. If the providers of healthcare systems could work more with these places, it may better inform them about people with migration background. From our experience in conducting the interviews and in trying to find interview partners, we found it was important to work with professionals of the same culture to contact the desired population. Another way to reach PwM may be to use media (e.g., radio, TV, and newspaper) relevant to that culture to disseminate information about dementia and available services. Because there are differences between and within cultures, it is important to engage the people affected themselves in the design of services and obtain their opinion directly [31].

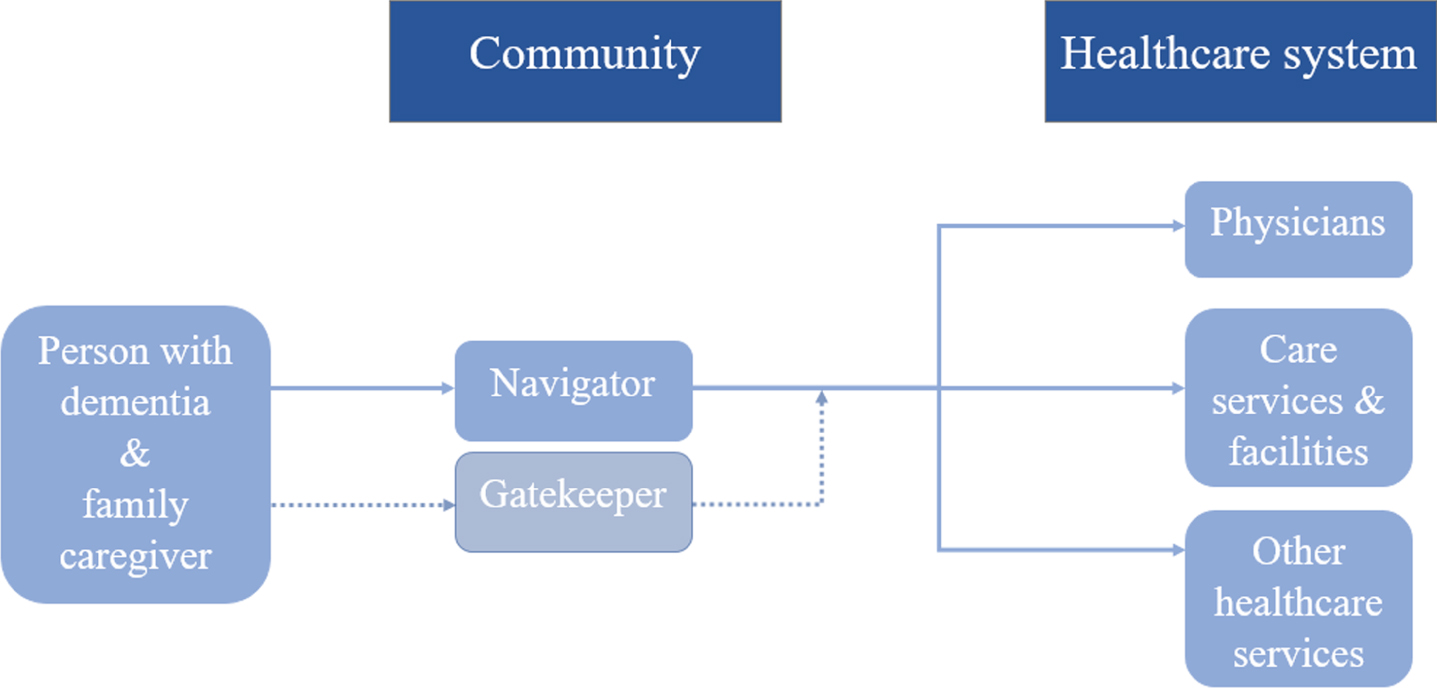

Based on this research, we propose an approach to navigate the healthcare system that supports systematic implementation of current concepts (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Proposed approach for navigation in the healthcare system.

On the community level, navigators should be available to people with Turkish migration background and dementia as well as their family members. These navigators would specifically provide them with information on dementia and help them access the healthcare system and formal healthcare services, e.g., which doctors to consult and where they can obtain caregiving help. In a best-case scenario, these navigators should be of the same culture, or at least have knowledge of and familiarity with Turkish culture, so they know what is valued when providing information to affected people [32, 33].

In Germany, certain cities and communities (e.g., Herne) offer “intercultural dementia guides” to help people in dealing with dementia. These types of useful services should be implemented nationwide. On the healthcare system level, people and institutions should be culturally sensitive in their approaches and services. From the perspectives of current participants, no unique and targeted services were needed for people with Turkish background. Rather, they wanted an awareness, knowledge, and a few alterations to the current system to embrace the Turkish culture. This is aligned with the basic principle of person-centered care. An optional step in this model are the gatekeepers. These are specialized options such as support groups for family members in the native language if needed. Gatekeepers can also serve as a way to help the people affected find their way into the healthcare system.

Of course, this proposal leaves room for discussion. For example, the intercultural dementia guides could also be a form of dementia care manager (DCM), a successful concept that was implemented by the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases Rostock/Greifswald in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. In this model, specially-trained DCMs visit PwD and their family caregivers at home and offer help and advice regarding their situation [34]. In terms of gatekeeper services, a suggestion would be to build intercultural dementia networks where people affected can be educated, obtain support from people in the same situation and be easily integrated into the healthcare system.

One might expect different outcomes from this study because PwM with dementia not only face challenges associated with dementia but also may face cultural barriers reported in previous research such as language barriers, different conceptualizations of health and disease, fear of stigmatization or a different organization of healthcare systems in the countries of origin [35, 36]. That situation is not the case in this study. The participants faced similar challenges as the population without migration background. However, the small and selective sample of eight participants needs to be considered when interpreting the results. If more people were interviewed, the analyses might have shown more and/or different experiences from those reported in this study. Furthermore, this population might be considered integrated in the healthcare landscape with better knowledge about the healthcare system and its available services. Hence, they could only report about the non-utilization of healthcare services retrospectively. Furthermore, most participants were proactive regarding help-seeking, e.g., visiting and telephoning offices. Therefore, they may not be representative of populations that are less or not integrated with healthcare systems and less likely to actively seek and accept help. Additionally, most participants wished for a translator to be present during the interviews. The translators were of the same culture and were working in the field of migration and health or, in one case, was a friend of the participant. This could have influenced the response behavior of the interviewed persons.

Although a translator was present during most of the interviews, the participants had good German language skills. This is another factor to consider when interpreting these results. Possessing good German language skills can make it easier to reach out to professionals and communicate with them, as well as obtain help and support. These are factors that distinguish them from people who lack knowledge of the healthcare system and language skills and, therefore, do not appear in the healthcare landscape. Including those people in research might lead to different results.

However, accessing this population is complicated. Recruiting proved to be difficult and tedious despite having approximately 40 stakeholder contacts either of the same culture working in the field of dementia and migration or at least working with our target group, who were more than willing to help find suitable interview partners. One reason for the lack of willingness to participate is that potential participants are very hesitant to participate in research. Of note, the mandatory signatures for informed consent forms and the length of study information sheets were cited as deterring factors.

Future research should explore how information could best be provided to communities of PwM. However, even more important is identifying measures to reach a population that is excluded from the healthcare landscape and, therefore, cannot be reached by stakeholders in the field of dementia and migration. In this regard, the future aim will be to present that PwM with dementia are not only underserved but also under-researched.

The challenge of a growing population of older Turkish migrants is shared between many countries. There are 6–9 million Turks living outside Turkey, who settled in countries such as Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine [37]. Turkish “guest workers” also went to countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Austria, and Sweden in the 1960s [38]. An estimated 500,000 Turkish people live in the United States. Even though differences in healthcare systems exist, migration-specific challenges might be of interest to others as well. We hope that our analysis encourages international research on people with Turkish migration background.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is the result of a collaboration with the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The authors would like to thank the participants of the interviews for taking part in the study and the stakeholders for their help in the recruiting process.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/20-0184r3).

REFERENCES

[1] | Statistisches Bundesamt (2019) Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit. Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund - Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2018 -, Statistisches Bundesamt, Wiesbaden. |

[2] | Brzoska P , Voigtlander S , Spallek J , Razum O ((2010) ) Utilization and effectiveness of medical rehabilitation in foreign nationals residing in Germany. Eur J Epidemiol 25: , 651–660. |

[3] | Schouler-Ocak M , Aichberger MC , Penka S , Kluge U , Heinz A ((2015) ) Mental disorders of immigrants in Germany. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 58: , 527–532. |

[4] | Spallek J , Razum O ((2007) ) Health of migrants: Deficiencies in the field of prevention. Med Klin (Munich) 102: , 451–456. |

[5] | Brzoska P , Razum O ((2015) ) Erreichbarkeit und Ergebnisqualität rehabilitativer Versorgung bei Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 58: , 553–558. |

[6] | Prince M , Wimo A , Guerchet M , Ali G-C , Wu Y-T , Prina M ((2015) ) The World Alzheimer Report 2015. The Global Impact of Dementia. An Analysis Of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost And Trends., Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI), London. |

[7] | Livingston G , Sommerlad A , Orgeta V , Costafreda SG , Huntley J , Ames D , Ballard C , Banerjee S , Burns A , Cohen-Mansfield J , Cooper C , Fox N , Gitlin LN , Howard R , Kales HC , Larson EB , Ritchie K , Rockwood K , Sampson EL , Samus Q , Schneider LS , Selbaek G , Teri L , Mukadam N ((2017) ) Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 390: , 2673–2734. |

[8] | Beattie A , Daker-White G , Gilliard J , Means R ((2005) ) ‘They don’t quite fit the way we organise our services’ - results from a UK field study of marginalised groups and dementia care. Disabil Soc 20: , 67–80. |

[9] | Mohammed S ((2017) ) A fragmented pathway: Experience of the South Asian community and the dementia care pathway - a care giver’s journey, University of Salford, Manchester. |

[10] | Nielsen TR , Vogel A , Phung TKT , Gade A , Waldemar G ((2011) ) Over- and under-diagnosis of dementia in ethnic minorities: A nationwide register-based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 26: , 1128–1135. |

[11] | Nielsen TR , Vogel A , Riepe MW , de Mendonca A , Rodriguez G , Nobili F , Gade A , Waldemar G ((2011) ) Assessment of dementia in ethnic minority patients in Europe: A European Alzheimer’s Disease Consortium survey. Int Psychogeriat 23: , 86–95. |

[12] | Monsees J , Hoffmann W , Thyrian JR ((2018) ) Prevalence of dementia in people with a migration background in Germany. Z Gerontol Geriatr 52: , 654–660. |

[13] | Mogar M , von Kutzleben M ((2015) ) Dementia in families with a Turkish migration background. Organization and characteristics of domestic care arrangements. Z Gerontol Geriatr 48: , 465–472. |

[14] | Dibelius O , Feldhaus-Plumin E , Piechotta-Henze G ((2015) ) Lebenswelten von Menschen mit Migrationserfahrungen und Demenz, Hogrefe, Bern. |

[15] | Yilmaz-Aslan Y , Brzoska P , Berens E-M , Salman R , Razum O ((2013) ) Gesundheitsversorgung älterer Menschen mit türkischem Migrationshintergrund. Qualitative Befragung von Gesundheitsmediatoren. Z Gerontol Geriatr 46: , 346–352. |

[16] | Tezcan-Güntekin H , Razum O ((2018) ) Pflegende Angehörige türkeistämmiger Menschen mit Demenz - Paradigmenwechsel von Ohnmacht zu Selbstmanagement. Pflege Gesellschaft 23: , 69–83. |

[17] | Sagbakken M , Storstein Spilker R , Ingebretsen R ((2018) ) Dementia and migration: Family care patterns merging with public care services. Qual Health Res 28: , 16–29. |

[18] | Gronemeyer R , Metzger J , Rothe V , Schultz O ((2017) ) Die fremde Seele ist ein dunkler Wald. Über den Umgang mit Demenz in Familien mit Migrationshintergrund, Psychosozial-Verlag, Gießen. |

[19] | Eichler T , Thyrian JR , Hertel J , Michalowsky B , Wucherer D , Dreier A , Kilimann I , Teipel S , Hoffmann W ((2015) ) Rates of formal diagnosis of dementia in primary care: The effect of screening. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 1: , 87–93. |

[20] | Klöppel S ((2010) ) Neue Möglichkeiten der automatisierten Demenzdiagnostik. Nervenarzt 81: , 1456–1459. |

[21] | Yin RK ((2016) ) Qualitative Research from Start to Finish, The Guilford Press, New York. |

[22] | Marcus B , Weigelt O , Hergert J , Gurt J , Gelléri P ((2017) ) The use of snowball sampling for multi source organizational research: Some cause for concern. Pers Psychol 70: , 635–673. |

[23] | Heckathorn DD , Cameron CJ ((2017) ) Network sampling: From snowball and multiplicity to respondent-driven sampling. Annu Rev Sociol 43: , 101–119. |

[24] | Mayring P ((2014) ) Qualitative Content Analysis. Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution, Klagenfurt. |

[25] | Joling KJ , Windle G , Droes RM , Huisman M , Hertogh C , Woods RT ((2017) ) What are the essential features of resilience for informal caregivers of people living with dementia? A Delphi consensus examination. Aging Ment Health 21: , 509–517. |

[26] | Schäufele M , Köhler L , Lode S , Weyerer S ((2007) ) Welche Faktoren sind mit subjektiver Belastung und Depressivität bei Pflegepersonen kognitiv beeinträchtigter älterer Menschen assoziiert? Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Studie in Deutschland. GeroPsych (Bern) 20: , 197–210. |

[27] | Thyrian JR , Eichler T , Hertel J , Wucherer D , Dreier A , Michalowsky B , Killimann I , Teipel S , Hoffmann W ((2015) ) Burden of behavioral and psychiatric symptoms in people screened positive for dementia in primary care: Results of the DelpHi-Study. J Alzheimers Dis 46: , 451–459. |

[28] | Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend, and Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (2018) Gemeinsam für Menschen mit Demenz. Bericht zur Umsetzung der Agenda der Allianz für Menschen mit Demenz 2014-2018, Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend and Bundesministerium für Gesundheit, Berlin. |

[29] | Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (2015) Gemeinsam für Menschen mit Demenz. Alles, was Sie zu den Lokalen Allianzen wissen müssen., Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend, Berlin. |

[30] | Brzoska P , Yilmaz-Aslan Y , Probst S ((2018) ) Considering diversity in nursing and palliative care - the example of migrants. Z Gerontol Geriatr 51: , 636–641. |

[31] | Alzheimer Europe (2018) The development of intercultural care and support for people with dementia from minority ethnic groups, Alzheimer Europe, Luxembourg. |

[32] | Hodge FS , Cadogan M , Itty TL , Williams A , Finney A ((2016) ) Culture-broker and medical decoder: Contributions of caregivers in American Indian cancer trajectories. J Community Support Oncol 14: , 221–228. |

[33] | Lindsay S , Tétrault S , Desmaris C , King G , Piéart G ((2014) ) Social workers as “cultural brokers” in providing culturally sensitive care to immigrant families raising a child with a physical disability. Health Soc Work 39: , e10–e20. |

[34] | Thyrian JR , Fiß T , Dreier A , Böwing G , Angelow A , Lueke S , Teipel S , Fleßa S , Grabe HJ , Freyberger HJ , Hoffmann W ((2012) ) Life- and person-centered help in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Germany (DelpHi): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 13: , 56. |

[35] | Bermejo I , Holzel LP , Kriston L , Harter M ((2012) ) Barriers in the attendance of health care interventions by immigrants. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 55: , 944–953. |

[36] | Blümel S ((2015) ) Migrant related health education: Concept and measures of the Federal Centre for Health Education, Germany. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 58: , 593–600. |

[37] | Pentikäinen O , Trier T ((2004) ) Between Integration And Resettlement: The Meskhetian Turks, European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI), Flensburg. |

[38] | Inglis C , Akgönül S , De Tapia S ((2009) ) Turks abroad: Settlers, citizens, transnationals. IJMS 11: , 104–119. |