-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Irit Krause, Einat Birk, Miriam Davidovits, Roxana Cleper, Leonard Blieden, Lidya Pinhas, Zahava Gamzo, Bella Eisenstein, Inferior vena cava diameter: a useful method for estimation of fluid status in children on haemodialysis, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Volume 16, Issue 6, June 2001, Pages 1203–1206, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/16.6.1203

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Background. An accurate assessment of fluid status in haemodialysis patients presents a significant challenge especially in growing children. Clinical parameters of hydration are not always reliable, and invasive methods such as measurement of central venous pressure cannot be used routinely. We evaluated the usefulness of inferior vena cava diameter (IVCD) measured by echocardiography in the estimation of hydration in children on haemodialysis.

Methods. Fifteen haemodialysis patients (mean age 14 years) were evaluated. Clinical assessment included patients’ symptoms, weight, blood pressure, heart rate, presence of oedema and vascular congestion, before and after dialysis session. Dry weight was assessed based on the above parameters. Fifty‐two echocardiographic studies immediately prior and 30–60 min following dialysis were performed. The anteroposterior IVCD was measured 1.5 cm below the diaphragm in the hepatic segment in supine position during normal inspiration and expiration. IVCD was expressed per body surface area.

Results. Following haemodialysis mean IVCD (average of expiration and inspiration) decreased from 1.12±0.38 to 0.75±0.26 cm/m2 (P<0.0001). Changes in IVCD were significantly correlated with alterations in body weight following dialysis (P<0.0001). The collapse index (per cent of change in IVCD in expiration vs inspiration) increased significantly after dialysis (P=0.035). IVCD clearly reflected alterations in fluid status. It did not vary significantly with changes in dry weight in a given patient.

Conclusions. Our findings support the applicability of VCD measurement in the estimation of hydration status in paediatric haemodialysis patients. The combination of clinical parameters and measurement of IVCD may enable more accurate evaluation of hydration of children on haemodialysis.

Introduction

An accurate assessment of hydration in haemodialysis patients presents a significant challenge especially in growing children. Dry weight is defined as an ideal weight at the end of regular dialysis treatment. Underestimation of dry weight may lead to hypovolaemia followed by hypotension, nausea, headache and muscle cramps, while overestimation may result in chronic fluid overload, oedema, hypertension and cardiac failure. Clinical parameters (blood pressure, heart rate, presence of oedema and venous congestion) are also influenced by factors other than hydration and are not always reliable. Invasive methods for evaluation of fluid status such as measurement of central venous pressure cannot be used routinely.

The measurement of inferior vena cava diameter (IVCD) by echocardiography has been suggested as a reliable method for evaluation of hydration in adult haemodialysis patients [1–4]. Significant correlation was found between IVCD and mean atrial pressure, total body volume as determined by radioiodinated serum albumin method and electrical bioimpedance [4]. To the best of our knowledge only one study reported IVCD as a parameter for estimation of dry weight in children on haemodialysis [5]. The present study was undertaken to evaluate the usefulness of IVCD, measured by echocardiography, in the assessment of hydration in children treated with haemodialysis.

Subjects and methods

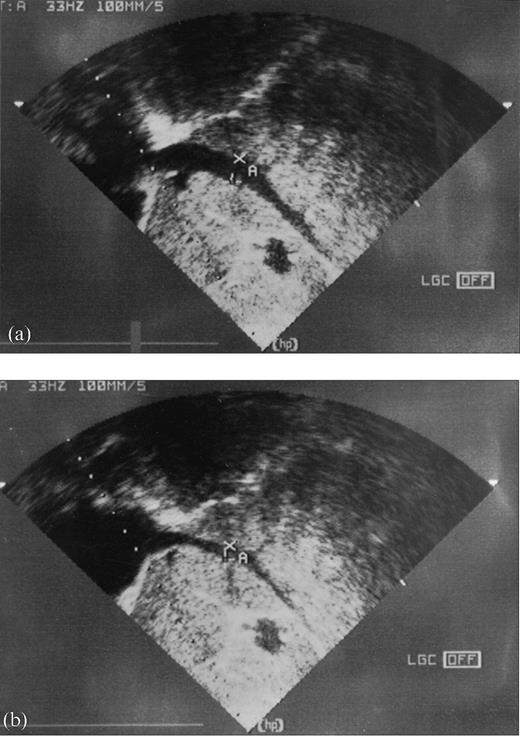

Fifteen haemodialysis patients (10 girls and 5 boys) were studied. The patients’ ages ranged from 4–21.2 years with a mean of 13.4±4.8 years (Table 1). The duration of haemodialysis therapy was 1–120 months. All patients were treated for 4 h three times a week except for 10 shorter treatments because of signs of dehydration. Weight was measured before and after dialysis. Hydration status was estimated according to the weight gain between the dialysis sessions and clinical criteria (Table 2). Periorbital and pretibial oedema, dyspnoea, orthopnoea and hypertension (blood pressure >95th percentile) were considered as signs of fluid overload. Muscle cramps, dizziness, hypotension and tachycardia indicated underhydration [6]. Target weight loss was adjusted empirically according to the above parameters. In 27 instances high levels of blood pressure (>95th percentile for age of systolic and/or diastolic values) before dialysis were recorded. Nine patients were treated regularly with antihypertensive drugs. None of the patients suffered from hypoalbuminaemia or heart failure. Four patients underwent successful kidney transplantation during the study period and IVCD was also evaluated after the transplantation. Echocardiographic studies were performed immediately prior to and 30–60 min following the dialysis session. Each patient was examined 2–6 times during a period of 21 months (a total of 104 studies). The anteroposterior IVCD was measured using 2‐dimensional and Doppler recordings 1.5 below the diaphragm in the hepatic segment in the supine position after 5–10 min of rest during normal expiration and inspiration while trying to avoid Valsalva manoeuvres (Figure 1). The same examiner performed all the measurements of IVCD. Mean IVCD was expressed as (IVCD in inspiration+IVCD in expiration)/2. IVCD was adjusted for body surface area (BSA) which was calculated according to a nomogram [7] and expressed as IVCD/BSA. Collapsibility index (CI) was determined as the per cent of decrease in IVCD in inspiration vs expiration (diameter on expiration‐diameter on inspiration)/maximal diameter on expiration×100. Baseline IVCD for a given patient was defined as IVCD measured in presence of the optimal weight (following cessation of regular dialysis session in the absence of clinical signs for under‐ or overhydration).

Results are reported as mean±SD. IVCD, heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure before and after ultrafiltration were compared by Student's paired t‐test. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) and the significance for it (P) were calculated between the values. P values less or equal to 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Anterior‐posterior IVCD measured by two‐dimensional and Doppler recording below the diaphragm at inspiration and expiration, (a) before haemodialysis, (b) after haemodialysis.

Patient's characteristics

| Patient's no. | Age at the beginning of the study (years) | BSA (m2) | Cause of ESRD |

| 1 | 16 | 1.4 | Reflux nephropathy |

| 2 | 17 | 1.0 | Lupus nephritis |

| 3 | 18 | 1.08 | Focal segmental |

| glomerulosclerosis | |||

| 4 | 21 | 1.65 | Idiopathic rapidly |

| progressive GN | |||

| 5 | 4 | 0.5 | HUS |

| 6 | 9.5 | 1.0 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 7 | 11 | 0.9 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 8 | 17 | 1.4 | Reflux nephropathy |

| 9 | 14 | 1.4 | Henoch‐Schonlein |

| purpura | |||

| 10 | 9 | 1.2 | Unknown |

| 11 | 18 | 1.3 | Focal segmental |

| glomerulosclerosis | |||

| 12 | 18 | 0.9 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 13 | 10.5 | 0.9 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 14 | 10 | 1.0 | ATN |

| 15 | 13 | 1.1 | Bilateral Wilms |

| tumour |

| Patient's no. | Age at the beginning of the study (years) | BSA (m2) | Cause of ESRD |

| 1 | 16 | 1.4 | Reflux nephropathy |

| 2 | 17 | 1.0 | Lupus nephritis |

| 3 | 18 | 1.08 | Focal segmental |

| glomerulosclerosis | |||

| 4 | 21 | 1.65 | Idiopathic rapidly |

| progressive GN | |||

| 5 | 4 | 0.5 | HUS |

| 6 | 9.5 | 1.0 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 7 | 11 | 0.9 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 8 | 17 | 1.4 | Reflux nephropathy |

| 9 | 14 | 1.4 | Henoch‐Schonlein |

| purpura | |||

| 10 | 9 | 1.2 | Unknown |

| 11 | 18 | 1.3 | Focal segmental |

| glomerulosclerosis | |||

| 12 | 18 | 0.9 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 13 | 10.5 | 0.9 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 14 | 10 | 1.0 | ATN |

| 15 | 13 | 1.1 | Bilateral Wilms |

| tumour |

Patient's characteristics

| Patient's no. | Age at the beginning of the study (years) | BSA (m2) | Cause of ESRD |

| 1 | 16 | 1.4 | Reflux nephropathy |

| 2 | 17 | 1.0 | Lupus nephritis |

| 3 | 18 | 1.08 | Focal segmental |

| glomerulosclerosis | |||

| 4 | 21 | 1.65 | Idiopathic rapidly |

| progressive GN | |||

| 5 | 4 | 0.5 | HUS |

| 6 | 9.5 | 1.0 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 7 | 11 | 0.9 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 8 | 17 | 1.4 | Reflux nephropathy |

| 9 | 14 | 1.4 | Henoch‐Schonlein |

| purpura | |||

| 10 | 9 | 1.2 | Unknown |

| 11 | 18 | 1.3 | Focal segmental |

| glomerulosclerosis | |||

| 12 | 18 | 0.9 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 13 | 10.5 | 0.9 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 14 | 10 | 1.0 | ATN |

| 15 | 13 | 1.1 | Bilateral Wilms |

| tumour |

| Patient's no. | Age at the beginning of the study (years) | BSA (m2) | Cause of ESRD |

| 1 | 16 | 1.4 | Reflux nephropathy |

| 2 | 17 | 1.0 | Lupus nephritis |

| 3 | 18 | 1.08 | Focal segmental |

| glomerulosclerosis | |||

| 4 | 21 | 1.65 | Idiopathic rapidly |

| progressive GN | |||

| 5 | 4 | 0.5 | HUS |

| 6 | 9.5 | 1.0 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 7 | 11 | 0.9 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 8 | 17 | 1.4 | Reflux nephropathy |

| 9 | 14 | 1.4 | Henoch‐Schonlein |

| purpura | |||

| 10 | 9 | 1.2 | Unknown |

| 11 | 18 | 1.3 | Focal segmental |

| glomerulosclerosis | |||

| 12 | 18 | 0.9 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 13 | 10.5 | 0.9 | Dysplastic kidneys |

| 14 | 10 | 1.0 | ATN |

| 15 | 13 | 1.1 | Bilateral Wilms |

| tumour |

Clinical findings before and after ultrafiltration therapy (UF), number of events

| Clinical findings | Before UF | After UF |

| Oedema (periorbital or pretibial) | 24/52 | 0/52 |

| Dyspnoea/orthopnoea | 2/52 | 0/52 |

| Hypertension (>95 pers) [9] | 18/52 | 21/52 |

| Tachycardia (>95 pers) [9] | 4/52 | 9/52 |

| Dizziness | 0/52 | 4/52 |

| Muscular cramps | 0/52 | 1/52 |

| Clinical findings | Before UF | After UF |

| Oedema (periorbital or pretibial) | 24/52 | 0/52 |

| Dyspnoea/orthopnoea | 2/52 | 0/52 |

| Hypertension (>95 pers) [9] | 18/52 | 21/52 |

| Tachycardia (>95 pers) [9] | 4/52 | 9/52 |

| Dizziness | 0/52 | 4/52 |

| Muscular cramps | 0/52 | 1/52 |

Clinical findings before and after ultrafiltration therapy (UF), number of events

| Clinical findings | Before UF | After UF |

| Oedema (periorbital or pretibial) | 24/52 | 0/52 |

| Dyspnoea/orthopnoea | 2/52 | 0/52 |

| Hypertension (>95 pers) [9] | 18/52 | 21/52 |

| Tachycardia (>95 pers) [9] | 4/52 | 9/52 |

| Dizziness | 0/52 | 4/52 |

| Muscular cramps | 0/52 | 1/52 |

| Clinical findings | Before UF | After UF |

| Oedema (periorbital or pretibial) | 24/52 | 0/52 |

| Dyspnoea/orthopnoea | 2/52 | 0/52 |

| Hypertension (>95 pers) [9] | 18/52 | 21/52 |

| Tachycardia (>95 pers) [9] | 4/52 | 9/52 |

| Dizziness | 0/52 | 4/52 |

| Muscular cramps | 0/52 | 1/52 |

Results

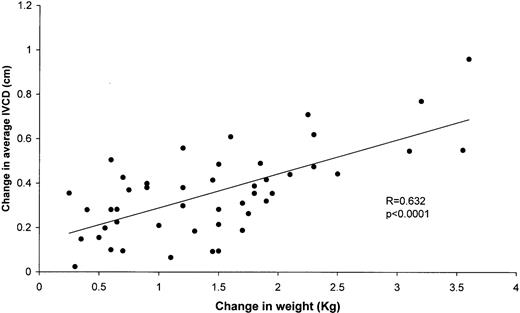

Following haemodialysis expiratory IVCD (IVCDe) decreased from 1.26±0.38 to 0.89±0.3 cm/m2 (P<0.0001) and inspiratory IVCD (IVCDi) from 0.98±0.39 to 0.61±0.23 cm/m2 (P<0.0001). Mean IVCD (IVCDm) decreased from 1.12±0.38 to 0.75± 0.26 cm/m2 (P<0.0001). The changes in IVCDm as well as in IVCDe and IVCDi were significantly correlated with alterations in body weight following dialysis (r=0.632, P<0.0001) (Figure 2). The collapsibility index increased after ultrafiltration therapy from 24.1±11.4 to 29±11.4%, P=0.035. Cases in which high blood pressure was recorded before dialysis session were studied separately (n=27). IVCDi, IVCDe and IVCDm measured in the presence of hypertension were 1.14±0.45, 1.44±0.42 and 1.29± 0.42 cm/m2 before dialysis respectively and 0.69±0.25, 1.00±0.34 and 0.85±0.29 cm/m2 after dialysis. IVCDi, IVCDe and IVCDm measured in the presence of normal blood pressure were 0.83±0.29, 1.11±0.32, 0.97±0.3 cm/m2 before dialysis and 0.53±0.17, 0.78±0.22 and 0.66±0.19 cm/m2 after dialysis respectively. Inspiratory, expiratory and mean IVCD before dialysis was significantly higher in presence of hypertension (P=0.008, 0.006 respectively). The differences in IVCD between the hypertensive and the normotensive groups remained statistically significant after dialysis (P=0.02). Despite the differences in IVCD, the changes in the diameter following ultrafiltration were not significantly different between hypertensive and normotensive groups (0.36±0.14 cm/m2 and 0.35±0.24, P=0.8). There was no statistically significant correlation between variations in heart rate, blood pressure and changes in weight before and after dialysis. IVCD did not vary significantly with the changes in dry weight in a given patient. Although the weight of three patients increased considerably during the study period due to improved nutrition and growth, IVCD measured in the state of dry weight did not change significantly. Four patients were examined before and after kidney transplantation. All transplanted kidneys showed normal function and there were no signs of fluid overload. IVCD following transplantation was very similar to IVCD determined as normal for a given patient while on haemodialysis.

Correlation between changes in IVCD and weight following haemodialysis.

Discussion

Patients with end‐stage renal failure suffer from impaired regulation of body fluid balance. Excess fluid has to be removed by dialysis. At the beginning of each haemodialysis session target weight loss is determined according to the estimation of excess fluid volume in order to obtain the patient's optimal weight (dry weight). Underestimation of dry weight leads to complications of hypovolaemia with adverse symptoms such as dizziness, headache and muscle cramps and, in extreme cases, endangers perfusion to vital organs. Children are particularly susceptible to the changes in fluid volume and tolerate badly the unpleasant symptoms of hypovolaemia. In our patients signs of dehydration in the course of dialysis occurred in ten instances and the treatment was not completed because the patients refused to continue the treatment. Overestimation of the dry weight may cause chronic fluid overload and complications such as hypertension, congestive heart failure and pulmonary oedema. An accurate estimation of dry weight in children is particularly difficult because of changes in weight due to growth. Clinical parameters of hydration status are influenced by factors other than fluid volume and are not always reliable. Indeed, no signs of fluid overload were present in 46% of the patients prior to dialysis and no correlation was found between heart rate and blood pressure and excess of fluids. More reliable parameters such as mean atrial pressure and measurement of total blood volume by radioiodinated albumin are invasive. Several non‐invasive methods for estimation of hydration in haemodialysis patients have been reported. These include bioimpedance, levels of ANP and IVCD [4].

IVCD has been shown in previous studies to reflect the intravascular volume in adult haemodialysis patients and to correlate well with other methods for estimation of fluid volume [1]. To the best of our knowledge, only one study dealt with IVCD and the levels of ANP as non‐invasive methods for estimation of fluid status in children on haemodialysis [5]. In this study, IVCD, collapsibility indices of IVC, plasma concentration of ANP and plasma renin activity were measured in 12 children on haemodialysis and 12 age‐matched normal controls. The findings revealed increased IVCD and plasma ANP concentrations and decreased collapsibility of IVC due to overhydration in children on haemodialysis. No data exist regarding the correlation between IVCD and other techniques such as mean atrial pressure or electrical bioimpedance in paediatric patients. Several studies concluded that echocardiography of IVC may be a promising non‐invasive tool to estimate dry weight, but unfortunately we were unable to find any practical guidelines for the correlation between IVCD and dry weight. In our study, IVCD decreased significantly following dialysis and correlated well with the changes in weight. Collapsibility index of IVC increased after ultrafiltration therapy although the changes in this index had lesser statistical power. IVCD did not vary significantly with alterations of weight which were independent of changes in the fluid status. Three patients gained weight due to improved appetite but no significant change was observed in their IVCD. Thus, IVCD that was found to represent normovolaemia may serve as a reference value in an individual patient. In accordance to the study of Katzarski et al. in adults [8], IVCD in presence of hypertension was significantly higher than in absence of hypertension. These results indicate the importance of fluid overload in the pathogenesis of dialysis‐related hypertension in paediatric patients. The alterations in IVCD following dialysis did not differ between these two groups, thus the changes in IVCD may be useful in estimation of changes in fluid volume in hypertensive as well as normotensive patients.

Although promising, this method has several limitations. One of the obstacles is a lack of normal values for IVCD in adults and in children. In a study of 86 healthy adults the diameter of IVC varied widely (range 1.3–2.8 cm) and did not correlate with height, weight or body surface area [9]. IVCD of 12 children on haemodialysis and of normal age‐matched controls was expressed as index (IVCD/body surface area) [5]. IVCD in our study was expressed per BSA. Although it is reasonable that IVCD correlates with BSA, the precise relationship is not known because other factors such as heart rate, blood pressure and treatment with antihypertensive drugs may influence IVCD. Significant inter‐individual variations and presence of numerous factors which affect IVCD require large population studies in order to place the values of IVCD on nomograms. In the absence of standard values for IVCD, serial echocardiographic examinations were performed in every one of our patients during a long period of time to determine IVCD that correctly reflects the individual dry weight (i.e. each patient served as a control for himself). Another limitation of IVCD as an indicator of hydration is the fact that it mainly reflects the intravascular space. IVCD measured immediately after dialysis may not accurately represent the amount of total body water. It is recommended to measure the IVCD several hours following haemodialysis to achieve maximum refilling from the extravascular space. The profile of IVCD variations following dialysis seems to be influenced by the rate of ultrafiltration [8]. Higher rates of ultrafiltration are associated with more rapid refilling. In our patients IVCD was not measured serially during haemodialysis sessions due to technical difficulties, thus we cannot confirm the correlation between the variations of IVCD and ultrafiltration rate in the present study. IVCD was measured 30–60 min after cessation of ultrafiltration because waiting for several hours after the termination of dialysis presented a difficulty in an outpatient setting. This may be one of the study biases. We attempted to overcome this obstacle by performing numerous measurements on several occasions in each patient.

Keeping in mind the limitations of the method, IVCD measured by echocardiography may serve as an additional reliable parameter in estimation of hydration status in children treated with haemodialysis. Lack of standard normal values for IVCD and significant inter‐individual variations necessitate serial measurements in each patient in order to determine each patient's ‘normal’ IVCD. IVCD cannot be used as a single parameter for fluid status. The combination of clinical parameters and IVCD may accomplish more accurate evaluation of the hydration in children on haemodialysis and improve their quality of life.

Correspondence and offprint requests to: Irit Krause, MD, Nephrology Clinic and Dialysis Unit, Schneider Children's Medical Center of Israel, Petah‐Tiqva 49202, Israel.

References

Criex EC, Leunissen KML, Janssen JMA, et al. Echocardiography of the inferior vena cava is a simple and reliable tool for estimation of dry weight in haemodialysis patients.

Kusaba T, Yamaguchi K, Oda H, et al. Echocardiography of inferior vena cava for estimating fluid removed from patients undergoing hemodialysis.

Mandelbaum A, Ritz E. Vena cava diameter measurement for estimation of dry weight in haemodialysis patients.

Leunissen KML, Kouw P, Kooman JP, Chriex EC, de Vries PMJM, Donker AJM, van Hooff JP. New techniques to determine fluid status in hemodialysis patients.

Sonmez F, Mir S, Ozyurek AR, Cura A. The adjustment of post‐dialysis dry weight based on non‐invasive measurements in children.

Nicholson JF, Pesce MA. Laboratory medicine and refernce tables. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Arvin AM eds.

Katzarski KS, Nisell J, Randmaa I, Danielsson A, Freyschuss, Bergstrom J. A critical evaluation of ultrasound measurement of inferior vena cava diameter in assessing dry weight in normotensive and hypertensive hemodialysis patients.

Mandelbaum A, Link A, Wambach G, Ritz E. Vena‐cava‐Sonographie zur Beurteilung des Hydratationszustandes bei Niereninsuffizienz.

Comments