-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Elaine Burland, Patricia Martens, Marni Brownell, Malcolm Doupe, Don Fuchs, The Evaluation of a Fall Management Program in a Nursing Home Population, The Gerontologist, Volume 53, Issue 5, October 2013, Pages 828–838, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns197

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This study evaluates a nursing home Fall Management program to see if residents’ mobility increased and injurious falls decreased.

Administrative health care use and fall occurrence report data were analyzed from 2 rural health regions in Manitoba, Canada, from June 1, 2003 to March 31, 2008. A quasiexperimental, pre-post, comparison group design was used to compare rates of three outcomes, falls, injurious falls, and falls resulting in hospitalization, by RHA (program vs nonprogram nursing homes) and period (preprogram vs postprogram). Data collectors entered occurrence report information into spreadsheets. This was supplemented with administrative health care use data.

The program appears to have benefitted residents—falls trended upward, injurious falls remained stable, and hospitalized falls decreased significantly (0.036–0.021 per person-year [ppy]; p = .043). Compared with nonprogram residents in the postperiod, both groups had the same fall rate, but program residents had significantly fewer injurious falls (0.596–0.746 ppy; p = .02) and hospitalized falls (0.02–0.041 ppy; p = .023).

These results are among a small body of literature showing that Fall Management was associated with improved outcomes in program nursing homes from pre- to postperiod and compared with nonprogram nursing homes. This research provides some support for the benefits of being proactive and implementing injury prevention strategies universally and pre-emptively before a resident falls, helping to minimize injuries while keeping residents mobile and active. Larger scale research is needed to identify the true effectiveness of the Fall Management program and generalizability of results.

Falls and fall-related injuries among older, institutionalized adults are common problems, resulting in serious physical, psychological, and financial consequences for the people who have fallen, their family and friends, nursing home staff, and the larger community (Tideiksaar, 2002). Because efforts are being made to delay institutionalization by keeping people in their homes longer (Mitchell, Roos, & Shapiro, 2005), people are being admitted to nursing homes at older ages and higher levels of care (Sharkey et al. as cited in Przybysz, Dawson, & Leeb, 2009). These residents are therefore at a much higher risk of falling compared with their community-dwelling counterparts (Krueger, Brazil, & Lohfeld, 2001; Lach, 2010; Tideiksaar, 2002).

More than half of all nursing home residents fall each year, often repeatedly (Hofmann, Bankes, Javed, & Selhat, 2003; Kannus, Sievanen, Jarvinen, & Parkkari, 2005). Annual incidence rates for falls range from 1.5 to 3.0 falls per bed (Cameron et al., 2010; Vu, Weintraub, & Rubenstein, 2004), and approximately 25% of these falls result in a serious injury (Public Health Agency of Canada: Division of Aging and Seniors, 2005; Vu et al., 2004).

There are innumerable risk factors identified in the research literature that are associated with nursing home residents’ falls and injuries. As the number of risk factors increases, so does the risk of falling (Public Health Agency of Canada: Division of Aging and Seniors, 2005; Theodos, 2003). Although some risk factors are not modifiable (e.g., resident’s age, cognitive impairment, and chronic disease), many are, such as hazardous environments, improper footwear, and polypharmacy.

Fortunately, many seniors’ falls are preventable (Tideiksaar, 2002), including those that occur in nursing homes (Ray et al., 1997). However, some efforts to prevent falls can actually increase the risk of falling (Kane, 2001; Tideiksaar, 2002), such as the use of physical and/or chemical restraints (Rubenstein, Josephson, & Robbins 1994). The resulting decrease in residents’ activity contributes to muscle atrophy, which, in turn, decreases residents’ strength, balance, and ultimately confidence, all of which increase the risk of falling (Komara, 2005; Takasaki, 1997).

Fall management is a new approach to falls. It includes most of the principles of traditional fall prevention, but rather than focusing on preventing falls, the goal is to prevent or at least minimize injuries while simultaneously encouraging mobility and functionality (North Eastman Health Association [NEHA], 2005). Falling is an inherent risk of the activity (Lach, 2010), but it is recognized that “[a] patient who is not allowed to walk alone will very quickly become a patient who is unable to walk alone” (Patient Safety First, 2009).

Fall management is also consistent with efforts to reduce and eventually eliminate the use of restraints. This started in the United States with the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act in 1987, which mandated nursing homes to start finding alternatives to restraint use (Tideiksaar, 2002). Research by Thomas and colleagues (2012) shows that nursing homes advocating a patient safety culture had lower use of restraints and fewer residents who fell.

Given that fall management is a new approach, very little research has been conducted in this area, and none has assessed the effectiveness of such programs. Most research has been done on fall prevention programs, and some that use fall management language are still ultimately aimed at fall prevention, such as Rask and colleagues (2007) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality program by Taylor, Parmelee, Brown, and Ouslander (2005). A successful program is one that reduces falls.

The purpose of this research was to evaluate the effectiveness of a Fall Management program implemented in some nursing homes in the province of Manitoba, Canada.

The program is designed to increase resident mobility while minimizing injurious falls, through the implementation of multiple strategies including education for staff, residents, and families; risk reduction strategies; regular fall risk assessments and environmental audits; and a postfall protocol. It is collaborative and multidisciplinary, involving a care team of nurses, aides, dieticians, recreation coordinators, occupational therapists, and other nursing home staff (e.g., maintenance) who work together to provide the safest and highest quality of life for residents. Residents and their families are also encouraged to play an active role in this effort.

Staff was informed about the program in December 2004. No staff was added—the program was implemented within the existing budget and staffing levels.

Education and training were targeted at staff, residents and their families and friends, and the community. Staff received several program-related education sessions in the months prior to implementation, starting January 2005. There was a 1-hr introductory session, with a self-paced learning package for those unable to attend. The learning package contained information about falls, consequences, risk factors, promoting functionality, fall management strategies, and a quiz. This first education phase was followed by a half-day session, with shift modules for those unable to attend. These modules are information packages which are read by the staff, then reviewed with a nurse prior to their shift. Topics included the history of and reasons for falls and some fall management strategies—regular toileting, promoting functionality, restraint minimization, and the logo used to identify residents at high risk of falling. Once a nursing home received the half-day session, it was considered to be implementing the program. Because this half-day session was delivered to the nursing homes on different days, each had a different program start date.

Program information was communicated to residents, family, and friends via a pamphlet, discussions at the resident/family meeting with nursing home administration, posters displayed in the nursing home, and “falling star pins” worn by staff, which displayed the program logo. There was also an article about the program in the local community newspaper.

The program was rolled out at the institutional level—all residents, regardless of fall risk, are in the program, in contrast to many programs which are implemented only for those residents who have fallen or at high risk of doing so. The program interventions include (a) fall risk assessments, (b) individual and environmental audits, (c) injury prevention strategies (e.g., restraint minimization, prompted voiding, exercise and activities, proper nutrition, medication review, and assistive devices), and (d) a postfall protocol.

New tools and processes resulting from the program include a program guide, with assessment tools, checklists, guidelines, educational material, and a post-fall protocol.

It is important to study the nursing home setting because most research has been conducted in the community—a group with a different risk profile than institutionalized adults (Cameron & Kurrie, 2007; Cusimano, Kwok, & Spadafora, 2008). Fall-related interventions tested in the nursing home population have proven to be less effective than those tested in the community (Vu et al., 2004). Moreover, research that has been done in institutionalized settings is inconclusive—different interventions are studied, settings vary between countries, and outcomes are measured differently (e.g., percent of people who fall, total falls, falls per resident, and falls as time dependent; Cameron & Kurrie, 2007).

Design and Methods

Rates of falls, injurious falls, and hospitalized falls were compared with program nursing homes from pre- to postperiod and with nonprogram nursing homes, to determine if the program was associated with improved outcomes. Individual-level nursing home data were analyzed using a quasiexperimental, pre-post, comparison group design. The following covariates were included: fall-risk drug use, polypharmacy, dementia, level of care, age, and sex. These were chosen because they are well-known fall risk factors.

Study Setting

This study took place in nursing homes in two regional health authorities (RHAs) in Manitoba, Canada. Nursing homes are residential facilities for predominantly older persons with chronic illness or disability. All five of the nursing homes in North Eastman RHA (NEHA) constitute the program nursing homes where the Fall Management program was implemented in 2005. These were matched with seven similar nursing homes in terms of sex, age, level of care, use of fall risk drugs, and dementia status, in the adjacent Interlake RHA (IRHA) none of which had a formal fall program in place during the study period. Both RHAs are adjacent to Manitoba’s capital city Winnipeg, where roughly half of the province’s population of 1.2 million people resides. Both NEHA and IRHA are rural RHAs, but not remote.

These RHAs constitute roughly 10% of the total Manitoba population. There were a total of 1,046 residents in the study nursing homes, which was approximately 5% of the total nursing home residents in the province. NEHA had 196 beds and IRHA had 200, roughly 8% of the total nursing home beds in Manitoba.

Data Sources and Study Period

Data from two different sources were used: (a) fall occurrence reports from the study nursing homes and (b) anonymized administrative health care utilization data for Manitoba residents. Both data sources contain an individual-level Personal Health Information Number (PHIN).

Fall Occurrence Reports.

—All nursing homes in this study require that an occurrence report be filled out each time a resident falls. These reports include identifying information about the resident along with information about the resident’s fall including (a) date of the fall, (b) time of fall, and (c) degree of injury sustained from the fall (i.e., none, minor, major, and death). The number of these reports was a measure of the number of falls.

Chart auditors were hired to collect needed information from the paper copies of the fall occurrence reports onto an electronic spreadsheet. These data were transferred to the provincial department of health where identifying information was removed and the PHIN was scrambled.

All chart auditors were trained to ensure reliability of the chart abstraction. Intrarater reliability was assessed at the beginning of the data collection process and was high for all of the data collectors. Each performed, on different days, a duplicate abstraction of their first 20 records collected. The two data collectors in NEHA each had a reliability of 99%—199 out of 200 responses were coded the same at the time of the retest. The data collector in IRHA had 100% agreement between test and retest.

Administrative Health Care Data.

—Population-based, deidentified administrative data from the Manitoba Population Health Research Data Repository, housed at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP; Roos et al., 2008), were used to derive an additional outcome variable (hospitalized falls) and several explanatory variables. These data are for the insured residents of Manitoba, which is almost the entire population, and include information about things such as the use of physician and hospital services, drug prescriptions, and long-term care use (Roos et al., 2008). An encrypted PHIN allowed linkage across databases and over time.

The Repository databases used in this research were (a) hospital claims, (b) medical claims, (c) long-term care (nursing homes), (d) pharmaceutical claims, and (e) registry files.

Variables Used in the Analyses.

—Several variables were used in this research (Table 1). The two main outcome variables were falls and injurious falls, obtained from nursing home occurrence reports. The remaining variables were obtained from the MCHP administrative databases.

Variable Definitions and Data Sources

| Variable . | Definition . | Data source . |

|---|---|---|

| Fall | Occurrence reports completed because of a resident’s fall | Nursing home occurrence report |

| Injurious fall | Occurrence report resident falls with a degree of injury designated as either minor, major, or death | Nursing home occurrence report |

| Accidental fall resulting in hospitalization | Fall codes in ICD-9-CM data from E880 to E888 | Hospital abstracts |

| Fall codes in ICD-10-CA data from W00 to W19 | ||

| Drugs that increase fall risk | The proportion of nursing home residents taking one or more of the following during 1-month periods: psychotropics, antiparkinsonian agents, antihypertensives, and narcotics | ATC codes in the Drug Programs Information Network (DPIN) |

| Polypharmacy [5+ drugs] | The proportion of nursing home residents dispensed five or more different drug categories of medications during 100-day periods | DPIN |

| Dementia | ICD-9-CM codes 290, 291.1, 291.2, 292.82, 294, 331, or 797 (for select dementia-related conditions) | Hospital abstracts (up to March 31, 2004) |

| ICD-9-CM codes 290, 294, 331, and 797 (for select dementia-related conditions) | Medical claims | |

| ICD-10-CA/CCI codes F00–F04, F05.1, F06.5, F06.6, F06.8, F06.9, F09, F10.7, F11.7, F12.7, F13.7, F14.7, F15.7, F16.7, F18.7, F19.7, G30, G31.0, G31.1, G31.9, G32.8, G91, G93.7, G94, or R54 (for select dementia-related conditions) | Hospital abstracts (from April 1, 2004 on) | |

| Level of care on admission to PCH | Level 1–6 | Long-term care database |

| Time at risk | Person-years | Long-term care database |

| Age | Date of birth | Registry files |

| Sex | Male/female | Registry files |

| Variable . | Definition . | Data source . |

|---|---|---|

| Fall | Occurrence reports completed because of a resident’s fall | Nursing home occurrence report |

| Injurious fall | Occurrence report resident falls with a degree of injury designated as either minor, major, or death | Nursing home occurrence report |

| Accidental fall resulting in hospitalization | Fall codes in ICD-9-CM data from E880 to E888 | Hospital abstracts |

| Fall codes in ICD-10-CA data from W00 to W19 | ||

| Drugs that increase fall risk | The proportion of nursing home residents taking one or more of the following during 1-month periods: psychotropics, antiparkinsonian agents, antihypertensives, and narcotics | ATC codes in the Drug Programs Information Network (DPIN) |

| Polypharmacy [5+ drugs] | The proportion of nursing home residents dispensed five or more different drug categories of medications during 100-day periods | DPIN |

| Dementia | ICD-9-CM codes 290, 291.1, 291.2, 292.82, 294, 331, or 797 (for select dementia-related conditions) | Hospital abstracts (up to March 31, 2004) |

| ICD-9-CM codes 290, 294, 331, and 797 (for select dementia-related conditions) | Medical claims | |

| ICD-10-CA/CCI codes F00–F04, F05.1, F06.5, F06.6, F06.8, F06.9, F09, F10.7, F11.7, F12.7, F13.7, F14.7, F15.7, F16.7, F18.7, F19.7, G30, G31.0, G31.1, G31.9, G32.8, G91, G93.7, G94, or R54 (for select dementia-related conditions) | Hospital abstracts (from April 1, 2004 on) | |

| Level of care on admission to PCH | Level 1–6 | Long-term care database |

| Time at risk | Person-years | Long-term care database |

| Age | Date of birth | Registry files |

| Sex | Male/female | Registry files |

Variable Definitions and Data Sources

| Variable . | Definition . | Data source . |

|---|---|---|

| Fall | Occurrence reports completed because of a resident’s fall | Nursing home occurrence report |

| Injurious fall | Occurrence report resident falls with a degree of injury designated as either minor, major, or death | Nursing home occurrence report |

| Accidental fall resulting in hospitalization | Fall codes in ICD-9-CM data from E880 to E888 | Hospital abstracts |

| Fall codes in ICD-10-CA data from W00 to W19 | ||

| Drugs that increase fall risk | The proportion of nursing home residents taking one or more of the following during 1-month periods: psychotropics, antiparkinsonian agents, antihypertensives, and narcotics | ATC codes in the Drug Programs Information Network (DPIN) |

| Polypharmacy [5+ drugs] | The proportion of nursing home residents dispensed five or more different drug categories of medications during 100-day periods | DPIN |

| Dementia | ICD-9-CM codes 290, 291.1, 291.2, 292.82, 294, 331, or 797 (for select dementia-related conditions) | Hospital abstracts (up to March 31, 2004) |

| ICD-9-CM codes 290, 294, 331, and 797 (for select dementia-related conditions) | Medical claims | |

| ICD-10-CA/CCI codes F00–F04, F05.1, F06.5, F06.6, F06.8, F06.9, F09, F10.7, F11.7, F12.7, F13.7, F14.7, F15.7, F16.7, F18.7, F19.7, G30, G31.0, G31.1, G31.9, G32.8, G91, G93.7, G94, or R54 (for select dementia-related conditions) | Hospital abstracts (from April 1, 2004 on) | |

| Level of care on admission to PCH | Level 1–6 | Long-term care database |

| Time at risk | Person-years | Long-term care database |

| Age | Date of birth | Registry files |

| Sex | Male/female | Registry files |

| Variable . | Definition . | Data source . |

|---|---|---|

| Fall | Occurrence reports completed because of a resident’s fall | Nursing home occurrence report |

| Injurious fall | Occurrence report resident falls with a degree of injury designated as either minor, major, or death | Nursing home occurrence report |

| Accidental fall resulting in hospitalization | Fall codes in ICD-9-CM data from E880 to E888 | Hospital abstracts |

| Fall codes in ICD-10-CA data from W00 to W19 | ||

| Drugs that increase fall risk | The proportion of nursing home residents taking one or more of the following during 1-month periods: psychotropics, antiparkinsonian agents, antihypertensives, and narcotics | ATC codes in the Drug Programs Information Network (DPIN) |

| Polypharmacy [5+ drugs] | The proportion of nursing home residents dispensed five or more different drug categories of medications during 100-day periods | DPIN |

| Dementia | ICD-9-CM codes 290, 291.1, 291.2, 292.82, 294, 331, or 797 (for select dementia-related conditions) | Hospital abstracts (up to March 31, 2004) |

| ICD-9-CM codes 290, 294, 331, and 797 (for select dementia-related conditions) | Medical claims | |

| ICD-10-CA/CCI codes F00–F04, F05.1, F06.5, F06.6, F06.8, F06.9, F09, F10.7, F11.7, F12.7, F13.7, F14.7, F15.7, F16.7, F18.7, F19.7, G30, G31.0, G31.1, G31.9, G32.8, G91, G93.7, G94, or R54 (for select dementia-related conditions) | Hospital abstracts (from April 1, 2004 on) | |

| Level of care on admission to PCH | Level 1–6 | Long-term care database |

| Time at risk | Person-years | Long-term care database |

| Age | Date of birth | Registry files |

| Sex | Male/female | Registry files |

The hospital claims database provided information on nursing home residents’ use of hospital services, which enabled the inclusion of a third outcome variable—falls resulting in hospitalization. ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CA fall codes within 30 days after a fall were counted. As of April 1, 2004, hospitals switched from using ICD-9-CM, to using ICD-10-CA/CCI, so both were included in the definition. Falls that occurred after hospital admission were not included in the analysis.

The explanatory variables used in this research were (a) dementia, (b) level of care on admission to nursing home (an overall measure of resident disability, ranging from minimal to maximum dependence in areas such as bathing, dressing, eating, and elimination; Doupe et al., 2011), (c) time at risk, (d) fall risk drugs, (e) polypharmacy (use of five and more drugs), (f) age, and (g) sex. Hospital and medical claims were used to define dementia, the long-term care database for level of care and time at risk, the Drug Program Information Network for fall risk drugs and polypharmacy, and the registry for age and sex (Table 1). Note that benzodiazepines and antidepressants are included in the definition of fall risk drugs used for this research—they are a subset of “psychotropic drugs” identified in Table 1: variable definitions and data sources.

Rates were analyzed as “per person-year” (ppy) to reflect the different lengths of time each resident was at risk of falling while living in the nursing home. Residents’ lengths of stay varied because of factors such as different admission and/or separation dates and hospitalization. Falls that occurred after hospital admission were excluded from the analysis.

The study period was June 1, 2003 to March 31, 2008, a total of 58 months. The preintervention period was almost 2 years—from June 1, 2003, until the date the program education was received by each study nursing home, which ranged from March 2 to April 18, 2005. The postintervention period was approximately 3 years—from the date the education was received until March 31, 2008.

An additional 5 years of hospital, medical, and pharmaceutical data prior to the study period (1998–2003) were used so that people with certain conditions prior to admission (i.e., dementia, fall-risk drug use, and polypharmacy), could be identified.

Analyses

Comparisons were made in terms of time (i.e., pre- and poststudy period), study group (i.e., with or without a fall program), and a Time × Study Group interaction, before and after adjustment for several confounding variables: (a) age, (b) sex, (c) level of care on admission, (d) polypharmacy rates, (e) rates of fall-risk drug use, and (f) dementia.

All of these covariates were controlled for in most of the analyses. Due to small numbers, it was only possible to keep level of care in the hospitalized falls model.

Because these data were counts, a Poisson distribution was used to model the two main outcomes—falls and injurious falls. Models were also run using a negative binomial distribution, but the data consistently better fit the Poisson distribution.

Because many of the same people were measured on more than one occasion (i.e., in the pre- and postperiod), these observations were correlated and not independent (Ballinger, 2004). This necessitated the use of a generalized estimating equation which is a method of parameter estimation, which corrects for within-subject correlations (Twisk, 2003).

For this research, models were run using different age groupings, definitions of polypharmacy and correlation structures in order to find the combination which best fit the data. Grouping age into (a) 80 years and under, (b) 81–86 years, (c) 87–91 years, and (d) 92+ years, and defining polypharmacy as residents taking five or more drugs simultaneously, yielded the best fitting models for the main outcomes (i.e., falls and injuries).

Descriptive analyses were conducted to provide an overview of the data and help to visualize trends. Chi-square tests were used to test for univariate associations between the categorical covariates by RHA and over time.

In order to allow time for nursing home staff to become familiar with the program, a 30-day washout period was incorporated when analyzing the data. For the 30-day period following the start of the program in each nursing home, data were excluded. The nonprogram nursing homes in the comparison nursing home (IRHA) were randomly matched with the program nursing homes in NEHA.

Results

Resident Characteristics

Analyses were conducted with 1,046 residents living in 12 nursing homes. Any residents living in the nursing home in both time periods were counted in each time period—NEHA had 310 residents in the preperiod and 411 in the postperiod (n = 721), and IRHA had 317 and 402, respectively (n = 719). Note that the postperiod was 14 months longer than the preperiod, thus accounting for the larger number of post-period residents in both RHAs.

Overall, the nursing home residents were not significantly different from each other by RHA or over time, from the preperiod to the postperiod, with the exception of a few variables (Table 2). Level of care and use of fall risk drugs increased significantly for residents in the program nursing homes from pre- to postperiod. In addition, although similar on all covariates in the preperiod, program nursing homes had a significantly greater burden of care and number of residents on polypharmacy than nonprogram nursing homes by the postperiod.

Explanatory and Outcome Variables in Program and Comparison Nursing Homes by Pre- and Postintervention Period

| Variables . | NEHA (program) (n = 721) . | IRHA (nonprogram) (n = 719) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (n = 310) . | Post (n = 411) . | Pre (n = 317) . | Post (n = 402) . | |

| 1. Explanatory | n (%) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 112 (36.1%) | 154 (37.5%) | 118 (37.2%) | 158 (39.3%) |

| Female | 198 (63.9%) | 257 (62.5%) | 199 (62.8%) | 244 (60.7%) |

| Age | ||||

| <80 | 84 (27.1%) | 110 (26.8%) | 78 (24.6%) | 113 (28.1%) |

| 80–86 | 82 (26.5%) | 129 (31.4%) | 98 (30.9%) | 115 (28.6%) |

| 87–91 | 87 (28.1%) | 104 (25.3%) | 89 (28.1%) | 107 (26.6%) |

| 92+ | 57 (18.4%) | 68 (18.4%) | 52 (16.4%) | 67 (16.7%) |

| Level of care | ||||

| 2 | 95 (30.6%)* | 89 (21.7%)*,** | 111 (35.0%) | 135 (33.6%)** |

| 3 | 131 (42.3%)* | 210 (51.1%)*,** | 123 (38.8%) | 173 (43.0%)** |

| 4 | 63 (20.3%) | 75 (18.2%) | 66 (20.8%) | 65 (16.2%) |

| 5 and 6 | 21 (6.8%) | 37 (9.0%) | 17 (5.4%) | 29 (7.2%) |

| Polypharmacy | 169 (54.5%) | 196 (47.7%)** | 168 (53.0%) | 233 (58.0%)** |

| Use of fall risk drugs | 82 (26.5%)* | 225 (54.7%)* | 88 (27.8%)* | 236 (58.7%)* |

| Dementia | 201 (64.8%) | 279 (67.9%) | 193 (60.9%) | 266 (66.2%) |

| 2. Outcomes | n (aRR) | |||

| Falls (n = 4,102) | 708 (1.95)** | 1,451 (2.24) | 550 (1.54)*,** | 1,393 (2.24)* |

| Injurious falls (n = 1,225) | 208 (0.599) | 361 (0.596)** | 209 (0.590)* | 447 (0.746)*,** |

| Hospitalized falls (n = 60) | 10 (0.036)* | 12 (0.020)*,** | 12 (0.034) | 26 (0.041)** |

| Variables . | NEHA (program) (n = 721) . | IRHA (nonprogram) (n = 719) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (n = 310) . | Post (n = 411) . | Pre (n = 317) . | Post (n = 402) . | |

| 1. Explanatory | n (%) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 112 (36.1%) | 154 (37.5%) | 118 (37.2%) | 158 (39.3%) |

| Female | 198 (63.9%) | 257 (62.5%) | 199 (62.8%) | 244 (60.7%) |

| Age | ||||

| <80 | 84 (27.1%) | 110 (26.8%) | 78 (24.6%) | 113 (28.1%) |

| 80–86 | 82 (26.5%) | 129 (31.4%) | 98 (30.9%) | 115 (28.6%) |

| 87–91 | 87 (28.1%) | 104 (25.3%) | 89 (28.1%) | 107 (26.6%) |

| 92+ | 57 (18.4%) | 68 (18.4%) | 52 (16.4%) | 67 (16.7%) |

| Level of care | ||||

| 2 | 95 (30.6%)* | 89 (21.7%)*,** | 111 (35.0%) | 135 (33.6%)** |

| 3 | 131 (42.3%)* | 210 (51.1%)*,** | 123 (38.8%) | 173 (43.0%)** |

| 4 | 63 (20.3%) | 75 (18.2%) | 66 (20.8%) | 65 (16.2%) |

| 5 and 6 | 21 (6.8%) | 37 (9.0%) | 17 (5.4%) | 29 (7.2%) |

| Polypharmacy | 169 (54.5%) | 196 (47.7%)** | 168 (53.0%) | 233 (58.0%)** |

| Use of fall risk drugs | 82 (26.5%)* | 225 (54.7%)* | 88 (27.8%)* | 236 (58.7%)* |

| Dementia | 201 (64.8%) | 279 (67.9%) | 193 (60.9%) | 266 (66.2%) |

| 2. Outcomes | n (aRR) | |||

| Falls (n = 4,102) | 708 (1.95)** | 1,451 (2.24) | 550 (1.54)*,** | 1,393 (2.24)* |

| Injurious falls (n = 1,225) | 208 (0.599) | 361 (0.596)** | 209 (0.590)* | 447 (0.746)*,** |

| Hospitalized falls (n = 60) | 10 (0.036)* | 12 (0.020)*,** | 12 (0.034) | 26 (0.041)** |

Note: See Figures 1–3 for aRRs and p-values for outcomes. NEHA = North Eastman Health Association; IRHA = Interlake Regional Health Authorities; aRR = adjusted relative rate.

*Significant difference between pre- and postperiod (p < .05).

**Significant difference between program and nonprogram nursing homes (p < .05).

Explanatory and Outcome Variables in Program and Comparison Nursing Homes by Pre- and Postintervention Period

| Variables . | NEHA (program) (n = 721) . | IRHA (nonprogram) (n = 719) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (n = 310) . | Post (n = 411) . | Pre (n = 317) . | Post (n = 402) . | |

| 1. Explanatory | n (%) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 112 (36.1%) | 154 (37.5%) | 118 (37.2%) | 158 (39.3%) |

| Female | 198 (63.9%) | 257 (62.5%) | 199 (62.8%) | 244 (60.7%) |

| Age | ||||

| <80 | 84 (27.1%) | 110 (26.8%) | 78 (24.6%) | 113 (28.1%) |

| 80–86 | 82 (26.5%) | 129 (31.4%) | 98 (30.9%) | 115 (28.6%) |

| 87–91 | 87 (28.1%) | 104 (25.3%) | 89 (28.1%) | 107 (26.6%) |

| 92+ | 57 (18.4%) | 68 (18.4%) | 52 (16.4%) | 67 (16.7%) |

| Level of care | ||||

| 2 | 95 (30.6%)* | 89 (21.7%)*,** | 111 (35.0%) | 135 (33.6%)** |

| 3 | 131 (42.3%)* | 210 (51.1%)*,** | 123 (38.8%) | 173 (43.0%)** |

| 4 | 63 (20.3%) | 75 (18.2%) | 66 (20.8%) | 65 (16.2%) |

| 5 and 6 | 21 (6.8%) | 37 (9.0%) | 17 (5.4%) | 29 (7.2%) |

| Polypharmacy | 169 (54.5%) | 196 (47.7%)** | 168 (53.0%) | 233 (58.0%)** |

| Use of fall risk drugs | 82 (26.5%)* | 225 (54.7%)* | 88 (27.8%)* | 236 (58.7%)* |

| Dementia | 201 (64.8%) | 279 (67.9%) | 193 (60.9%) | 266 (66.2%) |

| 2. Outcomes | n (aRR) | |||

| Falls (n = 4,102) | 708 (1.95)** | 1,451 (2.24) | 550 (1.54)*,** | 1,393 (2.24)* |

| Injurious falls (n = 1,225) | 208 (0.599) | 361 (0.596)** | 209 (0.590)* | 447 (0.746)*,** |

| Hospitalized falls (n = 60) | 10 (0.036)* | 12 (0.020)*,** | 12 (0.034) | 26 (0.041)** |

| Variables . | NEHA (program) (n = 721) . | IRHA (nonprogram) (n = 719) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (n = 310) . | Post (n = 411) . | Pre (n = 317) . | Post (n = 402) . | |

| 1. Explanatory | n (%) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 112 (36.1%) | 154 (37.5%) | 118 (37.2%) | 158 (39.3%) |

| Female | 198 (63.9%) | 257 (62.5%) | 199 (62.8%) | 244 (60.7%) |

| Age | ||||

| <80 | 84 (27.1%) | 110 (26.8%) | 78 (24.6%) | 113 (28.1%) |

| 80–86 | 82 (26.5%) | 129 (31.4%) | 98 (30.9%) | 115 (28.6%) |

| 87–91 | 87 (28.1%) | 104 (25.3%) | 89 (28.1%) | 107 (26.6%) |

| 92+ | 57 (18.4%) | 68 (18.4%) | 52 (16.4%) | 67 (16.7%) |

| Level of care | ||||

| 2 | 95 (30.6%)* | 89 (21.7%)*,** | 111 (35.0%) | 135 (33.6%)** |

| 3 | 131 (42.3%)* | 210 (51.1%)*,** | 123 (38.8%) | 173 (43.0%)** |

| 4 | 63 (20.3%) | 75 (18.2%) | 66 (20.8%) | 65 (16.2%) |

| 5 and 6 | 21 (6.8%) | 37 (9.0%) | 17 (5.4%) | 29 (7.2%) |

| Polypharmacy | 169 (54.5%) | 196 (47.7%)** | 168 (53.0%) | 233 (58.0%)** |

| Use of fall risk drugs | 82 (26.5%)* | 225 (54.7%)* | 88 (27.8%)* | 236 (58.7%)* |

| Dementia | 201 (64.8%) | 279 (67.9%) | 193 (60.9%) | 266 (66.2%) |

| 2. Outcomes | n (aRR) | |||

| Falls (n = 4,102) | 708 (1.95)** | 1,451 (2.24) | 550 (1.54)*,** | 1,393 (2.24)* |

| Injurious falls (n = 1,225) | 208 (0.599) | 361 (0.596)** | 209 (0.590)* | 447 (0.746)*,** |

| Hospitalized falls (n = 60) | 10 (0.036)* | 12 (0.020)*,** | 12 (0.034) | 26 (0.041)** |

Note: See Figures 1–3 for aRRs and p-values for outcomes. NEHA = North Eastman Health Association; IRHA = Interlake Regional Health Authorities; aRR = adjusted relative rate.

*Significant difference between pre- and postperiod (p < .05).

**Significant difference between program and nonprogram nursing homes (p < .05).

Falls, Injurious Falls, and Falls Resulting in Hospitalization

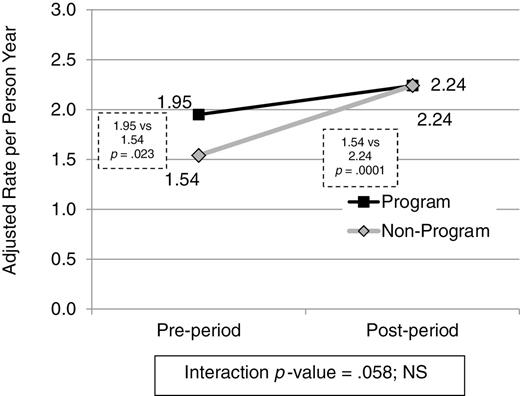

There were 4,102 total falls, 1,225 total injuries, and 60 hospitalized falls (Table 2). The rate of falls did not change in the program nursing homes (NEHA). The adjusted rate of falls per person-year in the program nursing homes did trend upward, from 1.95 in the preperiod to 2.24 in the postperiod, but was not statistically significant. Program nursing homes had significantly more falls than nonprogram nursing homes (IRHA) in the preperiod (1.95 vs 1.54; aRR = 1.27, 95% CIs = 1.03–1.56; p = .023) but a significant increase in falls in nonprogram nursing homes over time (1.54–2.24; aRR = 1.46, 95% CIs = 1.24–1.71; p < .0001) closed this gap. By the postperiod, the program and nonprogram nursing homes had the same fall rate of 2.24 falls ppy (Figure 1).

Adjusted rate of falls in program and comparison nursing homes by pre- and postintervention (n = 4,102 falls).

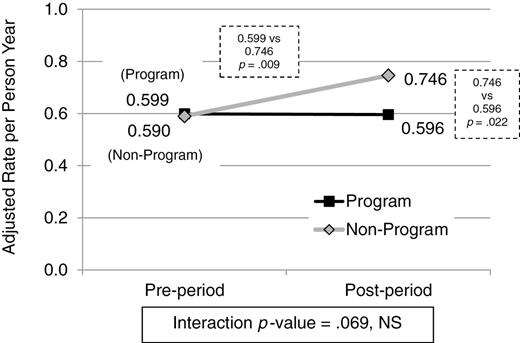

Injurious falls did not change in the program nursing homes. The adjusted rate of injurious falls was 0.599 falls ppy in the preperiod and 0.596 in the postperiod (aRR = 0.99, 95% CIs = 0.80–1.23; p = .49, NS). However, the program and nonprogram nursing homes had similar rates of injurious falls in the preperiod, but by the postperiod, the program nursing homes’ adjusted rate of 0.596 ppy was significantly lower than 0.746 in the nonprogram nursing homes (aRR = 0.79, 95% CIs = 0.67–0.96; p = .022; Figure 2).

Adjusted rate of injurious falls in program and comparison nursing homes by pre- and postintervention (n = 1,225 injuries).

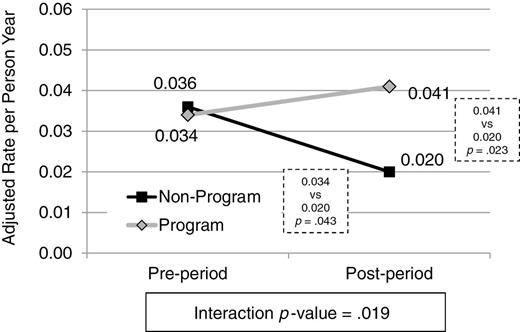

The most serious falls—those resulting in hospitalization—decreased significantly in the program nursing homes. The adjusted rate of falls resulting in a hospitalization decreased significantly in the program nursing homes from 0.036 in the preperiod to 0.020 ppy in the postperiod (aRR = 0.56, 95% CIs = 0.32–0.96; p = .043). Moreover, although similar in the preperiod, the rate of falls resulting in hospitalization was significantly lower in the program nursing homes compared with nonprogram nursing homes in the postperiod (0.020 vs 0.041; aRR = 0.49, 95% CIs = 0.28–0.88; p = .023), the rate in the program nursing homes decreased significantly, whereas the nonprogram nursing homes stayed the same (Figure 3).

Adjusted rate of falls resulting in hospitalization in program and comparison nursing homes by pre- and postintervention (n = 60 falls).

Discussion

Given that the Fall Management program was aimed at keeping nursing home residents mobile, it was thought that the rate of falls in the program nursing homes could possibly increase. There was an upward trend in falls, but it was not statistically significant. However, the program appears to have had a protective effect—despite this upward trend in falls, overall injuries remained stable and hospitalized falls decreased significantly.

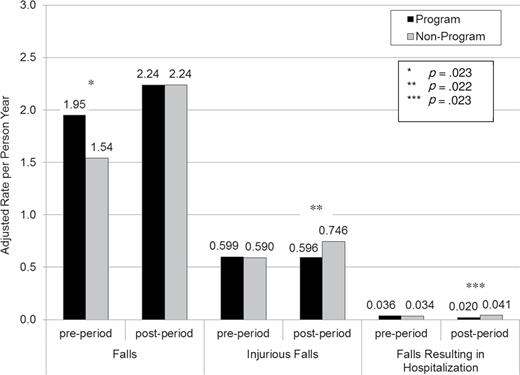

In addition, program residents fared significantly better than the nonprogram residents, in the post-period, after the program had been implemented all nursing homes had the same rate of falls, but residents in the program nursing homes had significantly fewer injurious falls and falls resulting in hospitalization than those in nonprogram nursing homes (Figure 4).

A review of open-ended information from a small sample of fall forms in the program nursing homes showed that overall, the frequency with which staff documented performing specific postfall protocol program procedures increased from 27.1% to 35.3% from pre- to postperiod. Documentation of individual procedures was erratic—some increased (e.g., checking vital signs, alerting others, assisting and monitoring resident, and specific fall management strategies), some decreased (e.g., reviewing fall reasons with resident/family and referral to another health professional), and some remained stable (e.g., documentation that chart was updated). Although overall documentation was low, it is not necessarily indicative of low implementation—staff could be preforming but not documenting procedures. Moreover, this increase, which was accompanied by improved outcomes for program residents, could be indicative of improved program compliance by staff.

Limitations

There are several limitations associated with this research. First, administrative data often do not contain all of the needed information (Ballinger, 2004; Creswell, 2003; Roos, Nicol, & Cageorge, 1987) because it has been collected for purposes other than research (e.g., payment of claims and planning; Institute for Clinical Evaluative Services, 2007; Sorensen, Sabroe, & Olsen, 1996). However, it does enable longitudinal retrospective analyses, which is less expensive and time consuming than prospective data collection.

Another limitation was the use of a nonrandomized design. Randomization helps to (a) increase the likelihood that intervention and comparison groups are similar at the beginning (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002) and (b) assess causality (Harris et al., 2006) by controlling for confounding variables and helping to isolate program effects (Creswell, 2003). Randomization was not possible because participants were pre-existing populations. However, the quasiexperimental design used provided an indication of program effects under “real life” conditions, which is more generalizable than the “lab setting” results of randomized designs (Bawden & Sonenstein, 2011). Moreover, using a pretest and comparison group provided information about outcomes in the absence of the program, thus contributing to the internal validity (Lie, 2007).

This research was also limited by a relatively short study period—there is an unavoidable lag between program implementation and improved outcomes (Commonwealth of Australia, 2009), so it is possible that program effects would have been stronger given more time. Moreover, there was only one time point measured in the postperiod, so there is no trend information. However, despite its short duration, this study is much longer than most comparable studies in the literature.

It is also possible that the use of occurrence reports was subject to reporting bias—if staff recorded falls more often after program implementation, this could explain why overall injuries in the program nursing homes remained stable rather than decreasing. However, even assuming there was an increase in the recording of falls and injuries in the program nursing homes, the fact that rates remained stable and injuries were significantly lower than the nonprogram nursing homes in the postperiod is encouraging. Moreover, hospital records, which are less subject to reporting bias and are thus a more valid indicator of injuries, showed that there was significant improvement in the program nursing homes—falls resulting in hospitalization decreased significantly from pre- to postperiod and were significantly lower than the nonprogram nursing homes in the postperiod.

Thus, it appears that the program nursing homes had beneficial effects for residents and nonprogram nursing homes had more difficulty preventing injuries when residents fell compared with the program nursing homes. Being proactive and implementing a Fall Management program universally before a resident falls is associated with improved outcomes.

It is important to note that at the end of this study, the nonprogram nursing homes in IRHA subsequently developed and implemented a fall prevention program.

Significance of Study

The results of this research fill many gaps in the current literature. First, this study is unique in that it links administrative data with nursing home data. Most previous studies used data derived solely from occurrence reports.

Second, this research provides information about the effectiveness of fall management—an area that is currently lacking in the literature. Most studies focused on the prevention of falls, rather than the prevention of injuries while maintaining activity and mobility (NEHA, 2005).

Third, these results contribute to other areas where there is need for more research: (a) patient safety in nursing homes, especially in Canadian settings (Canadian Patient Safety Institute, 2007) and (b) healthy aging in Canadian rural and remote communities.

Implications for Policy and Practice

These results show that a Fall Management program was associated with improved outcomes in program nursing homes from pre- to postperiod and compared with nonprogram nursing homes. Moreover, there is some support for being proactive and implementing a Fall Management program universally and pre-emptively before a resident falls, rather than targeting only those who have already fallen—keep residents as active and mobile as possible and employ injury prevention strategies to help minimize the chance of an injurious fall.

However, larger scale, longitudinal research is needed to identify the true effectiveness of the Fall Management program and generalizability of results. Is the program effective over time and/or in other populations?

If results support the effectiveness of the Fall Management program, similar programs should be implemented as a standard practice of care for all nursing home residents, rather than just targeting residents at risk of falling. Given the serious consequences of seniors’ falls (i.e., increased morbidity, mortality, and health care costs; Jensen, Nyberg, Gustafson, & Lundin-Olsson, 2003; Kiely, Kiel, Burrows, & Lipsitz, 1998) and the greater risk of falls among institutionalized seniors compared with their community counterparts (Kannus et al., 2005; Hoffman, Powell-Cope, MacClellan, & Bero, 2003), it is imperative that long-term care institutions be proactive (Trotto, 2001). Reducing injurious falls benefits the residents themselves, their families, nursing home staff, and the health care system.

It is also important to mitigate factors that can hinder the implementation of programs—lack of time, resources, and/or support (Capezuti, 2007). Use of computer-based data entry and analysis incorporating fall management assessments and care plans could potentially save time and improve care by facilitating work flow and improving communication with frontline workers who are often most familiar with residents’ fall risk (Taylor et al., 2007; Wagner, Capezuti, Taylor, Sattin, & Ouslander, 2005). Moreover, the work of Murphy and colleagues (2012) outlines steps that could lead to increased resources and support for fall programs. They conducted research that demonstrated program effectiveness and disseminated findings to legislators, care providers, and other stakeholders while building collaborative relationships with them, which lead to the funding and legislation of fall prevention in Connecticut.

Future Research

As with most research, some questions were answered and more were generated. Can the program be sustained? Have injuries started to decrease? How do rates compare with other regions in the province, and with other provinces and countries? Given more time and resources, the scope and depth of the analyses could be expanded by extending the study period and adding comparison groups.

As well, because injurious falls can result in substantial economic costs for nursing homes (Carroll, Delafuente, Cox, & Narayanan, 2008), incorporating financial data would provide information about whether the program was associated with lower costs. Did costs decrease in the program nursing homes over time? Were costs lower in the program nursing homes compared with the nonprogram nursing homes? If a program that is successful at stabilizing or reducing injuries can also be shown to be more economic, its chance of implementation is increased.

Future research could also investigate whether the program was associated with improved resident quality of life. As Bunn and colleagues (2008) found, fall programs need to incorporate older people’s perspectives about falls (as cited in Hill et al., 2011). This information could help to improve program effectiveness and sustainability.

Given the seriousness of the injuries seniors sustain from falling, it is imperative that there is continuous effort to minimize them. More research in this area would contribute greatly to this end.

Funding

Several contributors helped to fund this research, and I am extremely grateful for their assistance. This work was supported in part by the Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI) as a CPSI Studentship with matching funds from the Manitoba Institute for Patient Safety (MIPS); a 2009 Evelyn Shapiro Award; and assistance from my advisor, Dr. Patricia Martens, through her CIHR/PHAC Applied Public Chair Award.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my advisor, committee, family, and friends for their unwavering support and encouragement. The results and conclusions presented are those of the authors. No official endorsement by Manitoba Health or the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy is intended or should be inferred. Some of the data used in this study are from the Population Health Research Data Repository housed at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, University of Manitoba: (a) University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board #: H2009:112 and (b) Manitoba Health Information Privacy Committee #: 2009-2010-06.

References

Author notes

Decision Editor: Rachel Pruchno, PhD