Abstract

In order to investigate the possible involvement of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in the developmental origins of hepatic steatosis associated with undernourishment in utero, we herein employed a fetal undernourishment mouse model by maternal caloric restriction in three cohorts; cohort 1) assessment of hepatic steatosis and the ER stress response at 9 weeks of age (wks) before a high fat diet (HFD), cohort 2) assessment of hepatic steatosis and the ER stress response on a HFD at 17 wks, cohort 3) assessment of hepatic steatosis and the ER stress response at 22 wks on a HFD after the alleviation of ER stress with a chemical chaperone, tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA), from 17 wks to 22 wks. Undernourishment in utero significantly deteriorated hepatic steatosis and led to the significant integration of the ER stress response on a HFD at 17 wks. The alleviation of ER stress by the TUDCA treatment significantly improved the parameters of hepatic steatosis in pups with undernourishment in utero, but not in those with normal nourishment in utero at 22 wks. These results suggest the pivotal involvement of the integration of ER stress in the developmental origins of hepatic steatosis in association with undernourishment in utero.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is considered to be a hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome and the leading cause of hepatic dysfunction. The prevalence of NAFLD in the general population was previously estimated to be 20–30% in Western Countries and 5–18% in developing countries, such as Asia1. However, the rate of increases in the prevalence of NAFLD was shown to be markedly higher in developing countries than in developed countries2,3. The prevalence of NAFLD in China and Japan has nearly doubled in the last 10–15 years2 and has been attributed to the widespread availability of obesogenic cheap energy-dense foods. Nevertheless, the natural history of NAFLD remains unclear. Nobili et al. suggested the importance of the contribution of the programming hypothesis of pro-steatotic conditions presumably caused by undernourishment or overnourishment in utero4. Developing countries have been undergoing rapid economic improvements over the past few decades and a generation that was exposed to a low nutritional environment during fetal life due to maternal poverty and/or political turmoil has now shifted to a life of an obesogenic diet. Recent human5,6 and animal studies7,8,9 revealed that undernourishment in utero was causatively associated with the risk of NAFLD in later life. Therefore, it is plausible that not only the rapid shift to obesogenic energy-dense foods, but also exposure to undernourishment in utero, may underlie the marked increase in the rate of adult NAFLD in developing countries. However, how undernourishment in utero programs adult NAFLD has not yet been fully elucidated; therefore, effective preventive strategies against its prevalence, specifically in developing countries, have not been established.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the major site in cells for protein folding as well as trafficking and the critical site of the metabolism, secretion and homeostasis of proteins, lipids and glucose10,11. The ER is considered to play important roles in the regulation of lipid droplet number, composition and size and/or in lipogenesis as well as lipolysis; however, its involvement still remains unclear11,12. The ER plays a vital role in maintaining cellular and organismic metabolic homeostasis under normal physiological fluctuations in nutrients and conditions of excess10,11. However, a failure in the adaptive capacity of the ER, ER stress, has been shown to activate the unfolded protein response (UPR), which intersects with many different inflammatory and stress signaling pathways13. Thus, the ER stress response represents an evolutionary bottleneck that leads to common chronic diseases, including hepatic steatosis14,15, as well as a valuable target area for their prevention and treatment15. Experimental studies14,16 and evidence obtained from humans17,18 revealed the important causative involvement of ER stress in the development of hepatic steatosis.

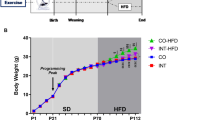

In the present study, we hypothesized that undernourishment in utero programs the up-regulation of ER stress in the adult liver on an obesogenic high fat diet (HFD) and causes the deterioration of hepatic steatosis. To prove the hypothesis, we employed a fetal undernourishment mouse model by maternal caloric restriction, which we established previously19,20,21,22,23, to three cohorts as illustrated in Fig. 1; cohort 1) assessment of hepatic steatosis and the ER stress response at 9 weeks of age (wks) before a HFD, cohort 2) assessment of hepatic steatosis and the ER stress response on a HFD at 17 wks, cohort 3) assessment of hepatic steatosis and the ER stress response at 22 wks on a HFD after the alleviation of ER stress by the chemical chaperone, tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) from 17 wks to 22 wks.

Schematic illustration of experimental procedures.

Three cohort studies were carried out until 9 wks (cohort 1), 17 wks (cohort 2) and 22 wks (cohort 3). Procedure for the caloric restriction of dams was described in Supplemental Figure S1.

Materials and Methods

Animal models

Pregnant C57Bl/6 mice (n = 20 [cohorts 1 and 2], n = 40 [cohort 3]) were purchased at 7.5 days post coitum (dpc) from Japan SLC, Inc. (Hamamatsu, Japan) and housed individually with free access to water during 12-h/12-h light/dark cycles under a regular chow diet (formula number D06121301, Research Diets Inc., New Brunswick, NJ). Dams were divided into two groups at 11.5 dpc. One group was fed the powdered regular chow ad libitum (AD, n = 10 [cohorts 1 and 2], n = 20 [cohort 3]). The maternal caloric intake of the other group was restricted to 60%, i.e. 40% reduction, (CR; n = 10 [cohorts 1 and 2], n = 20 [cohort 3]) of the ad libitum feeding dams (AD), as previously described19,20,21,22,23, between 11.5 dpc and 17.5 dpc (Supplemental Figure S1). Caloric restriction of 60%, i.e. 40% reduction, was adopted in the present study because liver weight and the liver weight/body weight ratio in the adult offspring of CR dams were both found to be significantly higher than those in AD dams in pilot studies of caloric restriction of 70%, 65%, 60% and 55% (Supplemental Table S1). Pups of maternal caloric restriction of 60% did not show significant changes in mean body weight or mean caloric intake (Supplemental Table S2) with all significant increase in liver weight (Supplemental Table S1), suggesting a possibility of lipid redistribution from adipose tissues and ectopic deposition in the liver in this animal model.

AD and CR dams were both fed ad libitum after delivery. All pups were cross fostered by dams fed ad libitum at 1.5 days of age, only male pups were selected by identifying black dots at the base of their tails and the number of pups was adjusted to 8 per litter. Only male pups were used in subsequent experiments because obesity and its associated metabolic disorders on a HFD were previously reported to be more prominent in males than in females in this animal model23. A regular chow diet (Rodent Lab Diet EQ 5L37, Japan SLC, Inc., Hamamatsu, Japan) was supplied to all of the offspring after weaning until 9 wks (Fig. 1). Each cohort study was carried out as an independent study.

In cohorts 2 and 3, a HFD containing 60% lipids (formula number D12492, Research Diets Inc.) was supplied to all of the pups from 9 to 17 wks and from 9 to 22 wks, respectively, for the purpose of mimicking a modern obesogenic diet, as previously described19,23,24 (Fig. 1).

All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the standards of humane animal care by the criteria outlined in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” prepared by the National Academy of Sciences and published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH publication 86–23 revised 1985) and approved by the Animal Research Committee, Hamamatsu University School of Medicine (H20-014).

ER stress alleviation by the TUDCA treatment under a HFD

In cohort 3, a HFD was supplied between 9 and 22 wks to AD and CR pups, as described above. At 17 wks, AD and CR pups were both randomly selected as a pup per litter and divided into two groups for Vehicle (Veh) or the TUDCA (TU; Merck Japan Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) treatment, resulting in four study groups being prepared, i.e. AD-Veh (n = 8), AD-TU (n = 10), CR-Veh (n = 7) and CR-TU (n = 10) groups (Fig. 1). TUDCA (TU), dissolved in distilled water and vehicle distilled water (Veh) were per orally administrated to the pups (TU: 0.5 g/kg/day) for five consecutive days a week from 17 to 22 wks until sampling (Fig. 1). Stainless needles (Product number; KN-348: Natsume. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were used for oral administration. At 22 wks, all pups were killed and the liver tissues as well as blood specimens were collected to assess hepatic steatosis and the ER stress response under a HFD (Fig. 1).

Blood and tissue sampling

Sampling points are illustrated in Fig. 1. Two trained technicians blinded to the study systematically decapitated each pup under ad libitum feeding and immediately measured blood glucose levels with ACC-CHEK Compact Plus (Roche Diagnostics Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The remaining blood samples were collected with heparin-coated glass tubes and centrifuged at 1200 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The plasma thus obtained was aliquoted and stored at −30 °C until assayed. The whole liver was dissected and weighed. Some of the liver tissue was fixed in 10% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin for a morphological analysis. The remaining tissue was snap frozen using liquid nitrogen in blocks and stored at −80 °C for mRNA or protein extraction.

Measurement of lipids

Total lipids in the liver were extracted with ice-cold 2:1 (vol/vol) chloroform/methanol. Triglyceride (TG) concentrations were measured using enzymatic assay kits (Sekisui Medical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Plasma lipoproteins were analyzed by an HPLC system at Skylight Biotec (Akita, Japan) according to the procedure described by Usui et al.25. The size of lipoprotein particles was determined based on individual elution times that corresponded to peaks on the chromatographic pattern of cholesterol fractions according to the procedure described by Okazaki et al.26.

Histological assessment of hepatic steatosis

The liver tissue blocks embedded in paraffin were cut into 3-μm-thick sections. Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining and Picrosirius Red staining (Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) were carried out. Hepatic steatosis (grade) and cell ballooning were assessed and scored as 0 ~ 3 and 0 ~ 2, respectively, according to the procedures described by Kleiner et al.27. Hydroxyproline content was measured using a commercially available kit.

A macrophage-specific F4/80 rat monoclonal antibody (MCA497GA, AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK) or CD45 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Proteintech Group, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was applied to the sections. Detection was performed with a polymer detection kit (ChemMate EnVisionTM; Dako Japan, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by a reaction with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine and counterstaining with hematoxylin. Eight separate images of a high-power field (HPF; ×400) were randomly separated and digitally captured and the numbers of positive cells were then counted and assessed as numbers per HPF.

Western blot

Twenty micrograms of protein from the liver tissues was loaded onto the SDS-Page gel and probed with primary antibodies against fatty acid synthase (FAS), sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 (SREBP1), phospho-inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (p-IRE1α), inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), phospho-eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (p-eIF2α), eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP), glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), or β-actin. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against SREBP1 and β-actin were obtained from Abnova, Taipei, Taiwan and BioVision, Milpitas, CA, USA, respectively. Rabbit polyclonal antibody against p-IRE1α was obtained from Abcam Japan, Tokyo, Japan. All of the other primary antibodies (rabbit monoclonal) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Boston, MA, USA. After washing, the membrane was incubated with a HRP-conjugated goat polyclonal second antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA; 1:1,000). The intensities of the immunoblots were quantified using ImageJ (version 1.48). In case of analysis of 11 specimens (cohort 1), single blot was used. In case of analysis of 19 specimens (cohort 2), two blots were assessed by comparison with one identical specimen (duplicate, total two) as an internal positive control, as previously described28,29. In case of analysis of 24 specimens (cohort 3), four blots were similarly assessed by comparison with two identical specimens (in duplicate, total four), as internal positive controls28,29.

Measurement of transaminase and insulin

Alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels were measured using FUJI DRI-CHEM 3500 (FUJIFILM Holdings Co., Tokyo, Japan). Insulin levels were measured using a commercially available kit.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

The gene expression levels of unspliced form X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1u; inactive form), spliced from X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1s; active form), Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and TNF receptor-associated factor 1 (TRAF1) were determined by quantitative RT-PCR using the High Capacity RNA to cDNA Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The expression of 18S ribosomal RNA was used as an internal control. The primers used were XBP1u; forward; GGATCCTGACGAGGTTCCAG, reverse; GCAGAGGTGCACATAGTCTGA, XBP1s; forward; GAAAGAAAGCCCGGATGAGC, reverse; ACCTGCTGCGGACTCA, TNF-α; forward; ACCCTCACACTCAGATCATCTTC, reverse; TGGTGGTTTGCTACGACGT, TRAF1; forward; GGGAGCCCACAATCCATGCA, reverse; TCGCTTCCACAGCTGCCTGA and 18S ribosomal RNA; forward; GGGAGCCTGAGAAACGGC, reverse; GGGTCGGGAGTGGGTAATTTT.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SDs. The significance of differences between two mean values was assessed using the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. The significance of differences among four mean values was assessed with the Steel-Dwass test. A p value of less than 0.05 was regarded as significant.

Results

Undernourishment in utero neither induced hepatic steatosis nor integrated the ER stress response in the liver at 9 wks before a HFD (cohort 1)

Liver weight and the liver weight/body weight ratio in CR pups were similar to those in AD pups (Fig. 2A,B). HE staining showed no apparent steatosis in AD (Fig. 2C) or CR pups (Fig. 2D) at 9 wks before a HFD. The protein expression levels of FAS and SREBP1 in CR pups were similar to those in AD pups (Fig. 2E,F). The number of F4/80-positive hepatic macrophages was in CR pups (10.5 ± 4.0 cells/HPF, n = 6) was similar to that in AD pups (11.0 ± 6.2 cells/HPF, n = 5).

Effects of undernourishment in utero on parameters of hepatic steatosis (A,B) or the ER stress response at 9 wks before a HFD (cohort 1). HE staining (C,D). Western blot analysis of FAS (E), SREBP1 (F), p-IRE1α (G), p-eIF2α (H), CHOP (I) and GRP78 (J). A pup per litter was randomly selected for the experiments (C–J). AU; arbitrary unit. All bands of Western blot analysis (E–J) were shown in Supplemental Figure S2.

The protein expression levels of p-IRE1α (Fig. 2G), p-eIF2α (Fig. 2H), CHOP (Fig. 2I) and GRP78 (Fig. 2J) in CR pups were similar to those in AD pups.

Undernourishment in utero significantly deteriorated hepatic steatosis and hepatic inflammatory reactions and significantly integrated the ER stress response at 17 wks on a HFD (cohort 2)

At 17 wks on a HFD, liver weight, the liver weight/body weight ratio, hepatic TG content and hepatic total TG amount were significantly higher in CR pups than in AD pups (Fig. 3A–D). HE staining (Fig. 3G,H) and gross appearance (Fig. 3I,J) showed that the deterioration of hepatic steatosis was greater in CR pups than in AD pups. FAS protein expression levels were significantly higher in CR pups than in AD pups (Fig. 3E), while SREBP1 protein expression levels were significantly lower in CR pups than in AD pups (Fig. 3F). The number of F4/80-positive hepatic macrophages was significantly higher in CR pups than in AD pups (Fig. 4A–C). TRAF1 gene expression levels were significantly higher in CR pups than in AD pups (Fig. 4E), while TNF-α levels were slightly higher in CR pups than in AD pups (Fig. 4D).

Effects of undernourishment in utero on parameters of hepatic steatosis (A–D) at 17 wks on a HFD (cohort 2). Western blot analysis of FAS (E) and SREBP1 (F). HE staining and gross appearance of the liver of AD (G,I)) and CR pups (H,J). A pup per litter was randomly selected for the experiments (C–J). *P < 0.05. ***P < 0.001. AU; arbitrary unit. All bands of Western blot analysis (E,F) were shown in Supplemental Figure S2.

Effects of undernourishment on the average number of hepatic macrophages (A–C) and ER stress response at 17 wks on a HFD (cohort 2). Gene expression of TNF-α (D) and TRAF1 (E) and gene splicing of XBP1u (XBP1s; F) by a quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Western blot analysis of p-IRE1α (G), p-eIF2α (H), CHOP (I) and GRP78, an endogenous chaperone protein that inhibits hepatic lipogenesis (J). A pup per litter was randomly selected for the experiments (A–J). *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001. AU; arbitrary unit. All bands of Western blot analysis (G–J) were shown in Supplemental Figure S2.

The integration of the ER stress response in CR pups relative to AD pups was indicated by a significant increase in the ratio of XBP1s/XBP1u gene expression (Fig. 4F) as well as the protein expression of p-IRE1α (Fig. 4G), p-eIF2α (Fig. 4H) and CHOP (Fig. 4I), but not GRP78, an endogenous chaperone protein that inhibits hepatic lipogenesis (Fig. 4J).

The amelioration of ER stress by the TUDCA treatment significantly alleviated hepatic steatosis, augmentation of hepatic macrophage numbers, the ER stress response and plasma lipid profiles in pups with undernourishment in utero, but not in normal control pups at 22 wks on a HFD (cohort 3)

The TUDCA treatment (17–22 wks) significantly decreased liver weight (Fig. 5A), the liver weight/body weight ratio (Fig. 5B), hepatic TG content (Fig. 5C) and hepatic total TG amount (Fig. 5D) in CR pups (CR-Veh v.s. CR-TU), but not in AD pups (AD-Veh v.s. AD-TU; Fig. 5A–D). HE staining (Fig. 5E,F) and gross appearance (Fig. 5G,H) also revealed that the TUDCA treatment improved steatosis in CR pups (CR-Veh v.s. CR-TU). The TUDCA treatment slightly decreased the protein expression levels of FAS (Fig. 5I), but not those of SREBP1 (Fig. 5J).

Effects of the TUDCA treatment on parameters of hepatic steatosis (A–D) at 22 wks on a HFD (cohort 3). HE staining (E,F) and gross appearance (G,H) of the liver. Western blot analysis of FAS (I) and SREBP1 (J). *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. AU; arbitrary unit. All bands of Western blot analysis (I,J) were shown in Supplemental Figure S2.

The TUDCA treatment significantly reduced the number of F4/80-positive hepatic macrophages in CR pups (Fig. 6A–C; CR-Veh v.s. CR-TU), but not in AD pups. The TUDCA treatment also slightly decreased the gene expression levels of TNF-α (Fig. 6D), but not those of TRAF1 (Fig. 6E).

Effects of the TUDCA treatment on the average number of hepatic macrophages (A–C) and ER stress response at 22 wks on a HFD (cohort 3). The gene expression of TNF-α (D) and TRAF1 (E) and gene splicing of XBP1u (XBP1s; F) by a quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Western blot analysis of p-IRE1α (G), p-eIF2α (H), CHOP (I) and GRP78, an endogenous chaperone protein that inhibits hepatic lipogenesis (J). *P < 0.05. AU; arbitrary unit. All bands of Western blot analysis (G–J) were shown in Supplemental Figure 2S.

The alleviation of the ER stress response in CR pups by the TUDCA treatment was indicated by a significant decrease in the gene splicing of XBP1u (XBP1s; Fig. 6F) (CR-Veh v.s. CR-TU) and in the protein expression of p-eIF2α (Fig. 6H) and CHOP (Fig. 6I). TUDCA treatment slightly decreased p-IRE1α protein expression in CR pups (Fig. 6G). The TUDCA treatment slightly increased the protein expression levels of GRP78, an endogenous chaperone protein that inhibits hepatic lipogenesis (Fig. 6J; CR-Veh v.s. CR-TU).

The TUDCA treatment significantly decreased the plasma levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and small dense LDL cholesterol in CR pups (CR-Veh v.s. CR-TU), but not in AD pups (Table 1A), but did not cause significant changes in the serum levels of chylomicron cholesterol, VLDL cholesterol, total triglycerides, glucose, or insulin (Table 1A).

Note; all bands of Western blots analysis were shown in Supplemental Figure S2. Results of Western blot analysis in cohort 2 and cohort 3 were summarized in Supplemental Table S3.

Discussion

We herein demonstrated, using this mouse animal model, that undernourishment in utero programmed the exacerbation of fatty liver on an obesogenic HFD (Fig. 3). The parameters of fatty liver, i.e. liver weight, the liver weight/body weight ratio, TG content and total TG amount, were significantly elevated by exposure to undernourishment in utero (AD v.s. CR; Fig. 3A–D). However, the scores of hepatic steatosis and cell ballooning in CR pups were similar to those in AD pups (Table 1B). Hepatic fibrosis assessed by Picrosirius Red staining and hydroxyproline content in CR pups were similar to those in AD pups (Supplemental Figure S3 and Table 1C). These results indicated that undernourishment in utero appeared to cause a simple increase in hepatic total TG storage in this animal model. A significant elevation in hepatic FAS protein expression levels, a rate-limiting enzyme in hepatic fatty acid synthesis, (Fig. 3E) supported this speculation. A significant decrease in SREBP1 protein expression levels was observed in the CR pups of this animal model (Fig. 3F), which we currently have no clear explanation for. Since we did not prove direct involvement of ER stress integration in the regulation of lipid synthesis in the present study, it is necessary to investigate the epigenetic modification of these critical substances, i.e. SREBP1 and FAS, to clarify entire pathophysiological association between the exacerbation of hepatic steatosis and undernourishment in utero.

Previous studies demonstrated the important involvement of chronic inflammation in the development of hepatic steatosis10,30,31. In the present study, a significant elevation in the average number of F4/80-positive hepatic macrophages was observed in CR pups at 17 wks (Fig. 4A–C) concomitant with a slight increase in TNF–α gene expression levels (Fig. 4D) as well as the significant augmentation of TRAF1 gene expression (Fig. 4E). Therefore, this animal model was considered to have appropriately mimicked the risk of hepatic steatosis caused by fetal undernourishment in humans5,6 and coincided with the findings of other animal studies7,8,9.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the major site in cells for protein folding as well as trafficking10,11 and is also the site of triglyceride formation, particularly in liver cells32. Experimental models11,15,16 and evidence obtained from humans17,33,34 revealed that the activation of specific UPR pathways with ER stress was causatively associated with the development of hepatic steatosis, especially on an obesogenic diet. However, to the best of our knowledge, it currently remains unclear whether undernourishment in utero primes ER stress in the adult liver during the process of fat accumulation.

In the present study, undernourishment in utero significantly augmented the protein expression levels of p-IRE1α, a phospho-inositol-requiring enzyme 1α, with endonuclease activity35 (Fig. 4G) and the gene expression levels of XBP1s produced by mRNA splicing36 (Fig. 4F). Regarding the PERK pathway37, undernourishment in utero significantly augmented the protein expression levels of p-eIF2α (Fig. 4H) and CHOP (Fig. 4I), but not those of GRP78 (Fig. 4J), an endogenous chaperone protein, which is typically induced by UPR and inhibits hepatic lipogenesis to maintain lipid homeostasis11,38. Therefore, undernourishment in utero activated the UPR pathways of lipogenesis (Fig. 4F–I), but did not affect the protein expression levels of GRP78, a suppressor of lipogenesis11,38 (Fig. 4J), suggesting that it may induce a kind of predisposition to hepatic fat deposition on an obesogenic HFD, presumably by differently programming hepatic GRP78 protein expression from other UPR pathways at 17 wks (cohort 2).

At 22 wks (cohort 3), significant deteriorations were still observed in all the parameters of hepatic steatosis in the pups with undernourishment in utero (Fig. 5A–D; AD-Veh v.s. CR-Veh). In order to elucidate the involvement of ER stress in the developmental origins of the risk of hepatic steatosis in more detail, we ameliorated ER stress by administering an oral treatment of TUDCA, a chemical chaperone39,40, from 17 to 22 wks on a HFD (Fig. 1). At 22 wks, the TUDCA treatment significantly improved the parameters of fatty liver (CR-Veh v.s. CR-TU), i.e. liver weight, the liver weight/body weight ratio, TG content, total TG amount (Fig. 5A–D) and some lipid profiles (Table 1A) concomitant with a significant decrease in F4/80-positive hepatic macrophage numbers (Fig. 6A–C), a slight decrease in the gene expression levels of TNF-α (Fig. 6D). TUDCA treatment significantly decreased the gene expression levels of XBP1s produced by mRNA splicing (CR-Veh v.s. CR-TU; Fig. 6F) and the protein expression levels of p-eIF2α (CR-Veh v.s. CR-TU; Fig. 6H) and CHOP (CR-Veh v.s. CR-TU; Fig. 6I), but not p-IRE1α (Fig. 6G), indicating the significant amelioration of ER stress. On the other hand, TUDCA treatments induced a slight paradoxical increase in the GRP78 protein expression, although statistically not significant (CR-Veh v.s. CR-TU; Fig. 6J). Since GRP78 protein inhibits hepatic lipogenesis11,38, the paradoxical slight increase in GRP78 protein expression might, at least partly, contribute to the amelioration of hepatic fat deposition by TUDCA treatment.

We summarized the changes in ER stress response in Supplemental Table S3. Consistent induction of protein expression levels of p-eIF2α and CHOP was observed both at 17 wks (Fig. 4H,I) (AD v.s. CR, cohort 2) and 22 wks (Fig. 6H,I) (AD-Veh v.s. CR-Veh, cohort 3), supporting an involvement of ER stress augmentation in the continuous deterioration of hepatic steatosis after undernourishment in utero. On the other hand, the gene splicing of XBP1u (XBP1s) (Fig. 4F) and protein expression of p-IRE1α (Fig. 4G) was transiently induced at 17 wks (cohort2), but not at 22 wks (Fig. 6F,G) (cohort 3); however, TUDCA treatment significantly suppressed gene splicing of XBP1u (XBP1s) only in CR pups (CR-Veh v.s. CR-TU), but not in AD pups (AD-Veh v.s. AD-TU) (Fig. 6F) (cohort 3), suggesting a potential involvement of XBP1s in the deterioration of hepatic steatosis between 17 wks and 22 wks. We have currently no clear explanation of the transient induction of p-IRE1α and its involvement in the continuous deterioration of hepatic steatosis between 17 wks and 22 wks. We speculated that heterogeneous factors might affect the complicated cascades of the p-IRE1α after their initial activation by the introduction of an obesogenic diet between 9 wks and 17 wks. Further studies are needed in order to confirm this speculation. Undernourishment in utero also caused consistent induction of the gene expression of endoplasmic reticulum–localized DnaJ 4 (ERdj4) and growth arrest and DNA damage inducible 34 (GADD34), but not activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), at 17 wks (cohort 2; AD v.s. CR) and 22 wks (cohort 3; AD-Veh v.s. CR-Veh) (Supplemental Table S4). Taken together, ER stress responses of at least p-eIF2α, CHOP, ERdj4, GADD34 and possibly XBP1s were considered to be involved in the deterioration of hepatic steatosis between both 17 wks and 22 wks.

Therefore, significant induction of ER stress markers (AD v.s. CR; cohort 2) and specific alleviation of hepatic steatosis by TUDCA treatment (CR-Veh v.s. CR-TU; cohort 3) together supported the specific involvement of ER stress integration in the relationship between the predisposition of hepatic steatosis and undernourishment in utero.

Thus the results of present study lead us to an interesting conclusion that undernourishment in utero may program the future integration of ER stress and subsequent UPR in the liver on an obesogenic diet in later life and may, as a consequence, induce the deterioration of hepatic steatosis. However, the concept of long-lasting programing of ER stress response has not been established so far and little information is available concerning its mechanistic background, as far as we know. Intensive investigation is necessary to clarify the mechanism of long-lasting programing of ER stress response. The candidates of the future investigation would be the epigenetic changes of the key substances of ER stress response, such as XBP1u, IRE1α, eIF2α, CHOP, GRP78 etc. On the other hand, gut-liver axis was recently proposed as a causatively linking between NAFLD and bowel inflammation41. Gjymishka et al., reported a possible involvement of ER stress in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases42. Since we orally treated TUDCA, the alleviation of ER stress in bowel microbiota may be a candidate of the mechanism inducing the improvement of hepatic steatosis. Future investigation is necessary.

A limitation in the present study was the lack of the assessment of insulin sensitivity. There were no significant changes in the levels of casual blood glucose and insulin levels, although there was a slight decrease in blood glucose levels in CR-TU pups compared to CR-Veh (Table 1A). Fasting blood glucose and insulin levels as well as glucose tolerance testing are necessary to assess the involvement of the changes of insulin sensitivity in the deterioration of hepatic steatosis in this animal model. Another limitation is that we assessed the numbers of F4/80-positive hepatic macrophages but did not show any data of their characteristics, such as apoptosis and population. Rather stable numbers of leukocyte common antigen CD45-positive cells (Supplemental Table S5) suggested a possible changes in the leukocyte population; however, more intensive analysis of the changes in the entire immune system including F4/80-positive hepatic macrophages is necessary to clarify the detailed association between ER stress integration and chronic inflammation during the development of hepatic steatosis.

The results of the present study suggested that integration of the ER stress response was causatively associated with the developmental origins of NAFLD in individuals who were born small, even in developed countries5,6, and/or in those exposed to a low nutritional environment during fetal life due to maternal poverty or political turmoil, especially in developing countries such as China2. It may also be a concern after future economic and political reconstructions of current conflict areas such as the Middle East and Africa.

In Japan, large numbers of young women have a strong desire to be thin43 and insufficient energy intake by pregnant Japanese women44 has been implicated in the continuous decrease in mean birth weights as well as the continuous increase in the rate of low birth weight neonates in Japan45. The prevalence of undernourishment in utero may explain, at least partly, why the prevalence of NAFLD in Japan has nearly doubled in the last 10–15 years2.

The ER stress response recently emerged as a promising therapeutic target in metabolic syndrome including NAFLD by chemical chaperones15 or specific foods, such as Asian traditional brown rice46. The present study provides an insight into the development of strategies for early interventions in a potential high-risk population of NAFLD, such as people born small or those exposed to maternal undernourishment during the fetal period due to socioeconomic conditions5,6.

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggest that ER stress integration plays a pivotal role in priming the deterioration of hepatic steatosis by undernourishment in utero.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Muramatsu-Kato, K. et al. Undernourishment in utero Primes Hepatic Steatosis in Adult Mice Offspring on an Obesogenic Diet; Involvement of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Sci. Rep. 5, 16867; doi: 10.1038/srep16867 (2015).

References

Masarone, M., Federico, A., Abenavoli, L., Loguercio, C. & Persico, M. Non alcoholic fatty liver: epidemiology and natural history. Reviews on recent clinical trials 9, 126–133 (2014).

Fan, J. G. et al. What are the risk factors and settings for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia-Pacific? Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology 22, 794–800, 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04952.x (2007).

Karbasi-Afshar, R., Saburi, A. & Khedmat, H. Cardiovascular disorders in the context of non-alcoholic Fatty liver disease: a literature review. The journal of Tehran Heart Center 9, 1–8 (2014).

Nobili, V., Cianfarani, S. & Agostoni, C. Programming, metabolic syndrome and NAFLD: the challenge of transforming a vicious cycle into a virtuous cycle. Journal of hepatology 52, 788–790, 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.02.010 (2010).

Nobili, V. et al. Intrauterine growth retardation, insulin resistance and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children. Diabetes care 30, 2638–2640, 10.2337/dc07-0281 (2007).

Alisi, A., Panera, N., Agostoni, C. & Nobili, V. Intrauterine growth retardation and nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease in children. International journal of endocrinology 2011, 269853, 10.1155/2011/269853 (2011).

Choi, G. Y. et al. Gender-specific programmed hepatic lipid dysregulation in intrauterine growth-restricted offspring. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 196, 477 e471-477, 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.024 (2007).

Yamada, M. et al. Early onset of fatty liver in growth-restricted rat fetuses and newborns. Congenital anomalies 51, 167–173, 10.1111/j.1741-4520.2011.00336.x (2011).

Wolfe, D. et al. Nutrient sensor-mediated programmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in low birthweight offspring. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 207, 308 e301-306, 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.07.033 (2012).

Hotamisligil, G. S. Inflammation and endoplasmic reticulum stress in obesity and diabetes. Int J Obes (Lond) 32, Suppl 7, S52–54, 10.1038/ijo.2008.238 (2008).

Hotamisligil, G. S. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell 140, 900–917, 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.034 (2010).

Gregor, M. F. & Hotamisligil, G. S. Thematic review series: Adipocyte Biology. Adipocyte stress: the endoplasmic reticulum and metabolic disease. Journal of lipid research 48, 1905–1914, 10.1194/jlr.R700007-JLR200 (2007).

Roy, B. & Lee, A. S. The mammalian endoplasmic reticulum stress response element consists of an evolutionarily conserved tripartite structure and interacts with a novel stress-inducible complex. Nucleic acids research 27, 1437–1443 (1999).

Fu, S., Watkins, S. M. & Hotamisligil, G. S. The role of endoplasmic reticulum in hepatic lipid homeostasis and stress signaling. Cell metabolism 15, 623–634, 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.007 (2012).

Gentile, C. L. & Pagliassotti, M. J. The endoplasmic reticulum as a potential therapeutic target in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Current opinion in investigational drugs 9, 1084–1088 (2008).

Gentile, C. L., Frye, M. A. & Pagliassotti, M. J. Fatty acids and the endoplasmic reticulum in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. BioFactors 37, 8–16, 10.1002/biof.135 (2011).

Gregor, M. F. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is reduced in tissues of obese subjects after weight loss. Diabetes 58, 693–700, 10.2337/db08-1220 (2009).

Lake, A. D. et al. The adaptive endoplasmic reticulum stress response to lipotoxicity in progressive human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology 137, 26–35, 10.1093/toxsci/kft230 (2014).

Yura, S. et al. Role of premature leptin surge in obesity resulting from intrauterine undernutrition. Cell metabolism 1, 371–378, 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.005 (2005).

Kawamura, M. et al. Undernutrition in utero augments systolic blood pressure and cardiac remodeling in adult mouse offspring: possible involvement of local cardiac angiotensin system in developmental origins of cardiovascular disease. Endocrinology 148, 1218–1225 (2007).

Kawamura, M. et al. Isocaloric high-protein diet ameliorates systolic blood pressure increase and cardiac remodeling caused by maternal caloric restriction in adult mouse offspring. Endocr J 56, 679–689, JST.JSTAGE/endocrj/K08E-286 [pii] (2009).

Kawamura, M. et al. Angiotensin II receptor blocker candesartan cilexetil, but not hydralazine hydrochloride, protects against mouse cardiac enlargement resulting from undernutrition in utero. Reprod Sci 16, 1005–1012, 1933719109345610 [pii] 10.1177/1933719109345610 (2009).

Kohmura, Y. K. et al. Association between body weight at weaning and remodeling in the subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese adult mice with undernourishment in utero. Reprod Sci 20, 813–827, 10.1177/1933719112466300 (2013).

Yura, S. et al. Neonatal exposure to leptin augments diet-induced obesity in leptin-deficient Ob/Ob mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16, 1289–1295, oby200857 [pii] 10.1038/oby.2008.57 (2008).

Usui, S., Hara, Y., Hosaki, S. & Okazaki, M. A new on-line dual enzymatic method for simultaneous quantification of cholesterol and triglycerides in lipoproteins by HPLC. Journal of lipid research 43, 805–814 (2002).

Okazaki, M., Usui, S., Fukui, A., Kubota, I. & Tomoike, H. Component analysis of HPLC profiles of unique lipoprotein subclass cholesterols for detection of coronary artery disease. Clinical chemistry 52, 2049–2053, 10.1373/clinchem.2006.070094 (2006).

Kleiner, D. E. et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 41, 1313–1321, 10.1002/hep.20701 (2005).

Terakawa, K. et al. Site-specific augmentation of amnion cyclooxygenase-2 and decidua vera phospholipase-A2 expression in labor: possible contribution of mechanical stretch and interleukin-1 to amnion prostaglandin synthesis. J Soc Gynecol Investig 9, 68–74 (2002).

Kakui, K. et al. Augmented endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) protein expression in human pregnant myometrium: possible involvement of eNOS promoter activation by estrogen via both estrogen receptor (ER)alpha and ERbeta. Mol Hum Reprod 10, 115–122 (2004).

Hotamisligil, G. S. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 444, 860–867, 10.1038/nature05485 (2006).

Than, N. N. & Newsome, P. N. A concise review of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Atherosclerosis 239, 192–202, 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.01.001 (2015).

Wolins, N. E., Brasaemle, D. L. & Bickel, P. E. A proposed model of fat packaging by exchangeable lipid droplet proteins. FEBS letters 580, 5484–5491, 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.040 (2006).

Sharma, N. K. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress markers are associated with obesity in nondiabetic subjects. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 93, 4532–4541, 10.1210/jc.2008-1001 (2008).

Boden, G. et al. Increase in endoplasmic reticulum stress-related proteins and genes in adipose tissue of obese, insulin-resistant individuals. Diabetes 57, 2438–2444, 10.2337/db08-0604 (2008).

Calfon, M. et al. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature 415, 92–96, 10.1038/415092a (2002).

Sidrauski, C. & Walter, P. The transmembrane kinase Ire1p is a site-specific endonuclease that initiates mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response. Cell 90, 1031–1039 (1997).

Oyadomari, S., Harding, H. P., Zhang, Y., Oyadomari, M. & Ron, D. Dephosphorylation of translation initiation factor 2alpha enhances glucose tolerance and attenuates hepatosteatosis in mice. Cell metabolism 7, 520–532, 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.04.011 (2008).

Kammoun, H. L. et al. GRP78 expression inhibits insulin and ER stress-induced SREBP-1c activation and reduces hepatic steatosis in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation 119, 1201–1215, 10.1172/JCI37007 (2009).

Ozcan, U. et al. Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science 313, 1137–1140, 10.1126/science.1128294 (2006).

Kawasaki, N., Asada, R., Saito, A., Kanemoto, S. & Imaizumi, K. Obesity-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress causes chronic inflammation in adipose tissue. Scientific Reports 2, 799, 10.1038/srep00799 (2012).

Kirpich, I. A., Marsano, L. S. & McClain, C. J. Gut-liver axis, nutrition and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clinical biochemistry, 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2015.06.023 (2015).

Gjymishka, A., Coman, R. M., Brusko, T. M. & Glover, S. C. Influence of host immunoregulatory genes, ER stress and gut microbiota on the shared pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease and Type 1 diabetes. Immunotherapy 5, 1357–1366, 10.2217/imt.13.130 (2013).

Hayashi, F., Takimoto, H., Yoshita, K. & Yoshiike, N. Perceived body size and desire for thinness of young Japanese women: a population-based survey. The British journal of nutrition 96, 1154–1162 (2006).

Kubota, K. et al. Changes of maternal dietary intake, bodyweight and fetal growth throughout pregnancy in pregnant Japanese women. The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research 39, 1383–1390, 10.1111/jog.12070 (2013).

Itoh, H. & Kanayama, N. Low bith weight and risk of obesity -Potential Problem of Japanese People- Curr Women Health Rev 5, 212–219, 10.2174/157340409790069989 (2009).

Kozuka, C. et al. Brown rice and its component, gamma-oryzanol, attenuate the preference for high-fat diet by decreasing hypothalamic endoplasmic reticulum stress in mice. Diabetes 61, 3084–3093, 10.2337/db11-1767 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mrs Nahoko Hakamata, Mrs Yumiko Yamamoto, Mrs Naoko Kondo, Mrs Miuta Sawai and Mrs Kazuko Sugiyama for their secretarial or technical assistance. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports, Japan (No. 24390273, No. 23659534, No. 15H04882).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.M.-K.; main contributor to the experiments and analyses. H.I.; study concept, design and obtained funding. Y.K.-K.; contributed to the lipid analysis. U.J.F.; contribution to RT-PCR analysis. N.T.; important intellectual content and technical support. C.Y.; histological assessment of steatosis. T.U.; statistical analysis and technical support. K.S.; important intellectual content and animal experiments. K.H.; contributed to the analysis of hepatic steatosis. T.S.; contributed to the analysis of lipid profiles and inflammation. Y.O.; study supervision and important intellectual content. N.K.; study supervision and important intellectual content. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Muramatsu-Kato, K., Itoh, H., Kohmura-Kobayashi, Y. et al. Undernourishment in utero Primes Hepatic Steatosis in Adult Mice Offspring on an Obesogenic Diet; Involvement of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Sci Rep 5, 16867 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16867

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16867

This article is cited by

-

Tcf7l2 in hepatocytes regulates de novo lipogenesis in diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice

Diabetologia (2023)

-

Maternal tadalafil therapy for fetal growth restriction prevents non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and adipocyte hypertrophy in the offspring

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Plasticity of histone modifications around Cidea and Cidec genes with secondary bile in the amelioration of developmentally-programmed hepatic steatosis

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.