Abstract

Objective To assess the frequency of faints and other medical emergencies experienced by staff of a UK dental hospital. To investigate the training they had received in the management of medical emergencies, their perception of readiness to deal with emergencies and future training needs.

Subjects All 193 clinical staff (dentists, hygienists, nurses and radiographers) of the University Dental Hospital of Manchester.

Design Structured questionnaire with covering letter, reminders sent to non-responders.

Results There was an 82% response. Fainting was the commonest event: other medical emergency events were experienced with an average frequency of 1.8 events per year, with the highest frequency reported by staff in oral surgery. Most expressed a need for further training: only 3% felt no need.

Conclusions Medical emergencies occur in dental hospital practice more frequently but in similar proportions to that found in general dental practice. There is a perceived need for further training among dental hospital staff in the management of medical emergencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The ability to manage medical emergencies is an important and on-going requirement for dental practitioners.1 Recently, studies have been carried out in Great Britain and Australia which report the medical emergencies experienced by general dental practitioners (GDPs) and their perceptions of readiness to manage such events.2,3,4 No such study has reported the experience of staff of a UK dental hospital, although in the United States, Malamed has published data on the medical emergency events which occurred at the University of Southern California School of Dentistry from 1973–1992.5

The purpose of this paper is to report the findings of a questionnaire survey of members of staff of the University Dental Hospital of Manchester which was carried out to learn of their experience of medical emergencies and how prepared they felt to manage such events. Where appropriate, these findings will be compared with those available from general dental practice.

The University Dental Hospital of Manchester is a dental teaching hospital providing training at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. It also provides a secondary and tertiary referral service for diagnosis and treatment of the full range of clinical dental specialities, together with a dental casualty service. Dental treatment under intravenous sedation is carried out and there is a general anaesthesia service for simple exodontia in children. In total around 75,000 patient attendances take place each year. Day-case and in-patient oral and maxillo-facial surgery is carried out in the nearby Manchester Royal Infirmary: staff working exclusively in this unit were not involved in the survey.

Aims

The aims of the study were to ascertain:

-

The number of faints experienced by hospital staff over a 12-month period

-

The nature and number of other medical emergency events experienced over a 10-year period or for as long as they had been working if less than this

-

The training received in management of medical emergencies both during training and following qualification

-

How well prepared staff felt to manage such events: (a) at qualification and (b) currently

-

How they felt their readiness might be improved.

Method

A structured questionnaire was devised, parts of which were similar to that used to survey GDPs,3 to enable comparisons to be made between the GDP sample and dentally qualified staff at the Dental Hospital regarding the types of medical emergencies experienced and the nature of training in their management. Numbered questionnaires with a covering letter were sent to all full- and part-time clinical members of staff of the University Dental Hospital of Manchester in April 1998, and a second questionnaire with a covering letter was sent 1 month later to those who initially did not respond. It asked when they had commenced working at the Dental Hospital and when the dentally qualified staff had graduated in order to gain an indication of the total number of years' experience over which the emergency events were being reported.

One person (GJA) entered data from the questionnaires onto a Microsoft 'Excel'® spreadsheet for analysis: 10% of the data were re-entered to ensure accuracy. They were then adapted and transferred onto the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (for Windows™) (©SPSS Inc) for further analysis.

Results

There were 203 forms sent: however, three staff members received duplicate forms; six did no clinical sessions at the Dental Hospital and one was on maternity leave, thus there was a sample population of 193. A total of 158 were returned, a response of 81.9%: all had been completed satisfactorily, apart from one respondent who did not state their occupation. In addition, one respondent, a radiographer, reported medical emergencies experienced in a general hospital accident and emergency department: her data were not included in the parts of the analysis concerning frequency of events, as it was our aim to report events, as far as possible, experienced in a dental hospital.

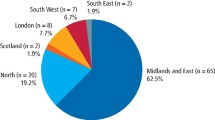

Among the dentally qualified members of staff, 84 forms were returned from 105 sent to those who carried out clinical work at the Dental Hospital (80.0%). Of the dentists who responded, there were 26 consultants, 28 registrars, senior registrars or lecturers, 11 house officers or senior house officers, two senior lecturers, 11 honorary teachers and six clinical assistants. Thirty-three of the dentally qualified staff worked in restorative dentistry, 25 in paediatric dentistry and orthodontics, eight in dental diagnostic science (comprising oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology), six in oral and maxillofacial surgery and one in dental public health: 11 did not state a speciality. Of the ancillary staff, there were 47 members of nursing staff, of whom 16 were students, 21 hygienists, of whom 16 were students and five radiographers. As stated above, one respondent did not state their occupation and the data from one radiographer were excluded. Dentally qualified members of staff reported working a mean of 5.4 clinical sessions a week and ancillary staff a mean of 8.3 (nursing staff 8.7, hygienists 5.8 and radiographers 7).

Medical emergency events reported

A total of 296 episodes of fainting were reported over a 12-month period by all respondents. The proportions of dental and ancillary staff reporting different numbers of faints is shown in Figure 1. Dentally qualified staff experienced a mean of 2.2 faints (with a standard deviation of 3.2, a median of 1 and a mode of 0) and ancillary staff a mean of 1.6 faints (with a standard deviation of 1.9, a median of 1 and a mode of 0). From the data, it was calculated that dentally qualified staff would experience four faints per full time equivalent (ie 10 clinical sessions a week) per year, compared with 1.9 faints per full time equivalent per year for ancillary staff. Thus dentally qualified staff reported about twice the number of faints, assuming a full-time equivalent working week for both groups.

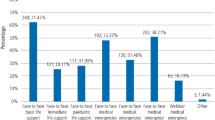

Apart from faints, there was a total of 862 emergency events reported in the survey over a 10-year period. These included 15 events associated with general anaesthesia (GA) and one episode of respiratory arrest was reported under intravenous sedation (IVS). Figure 2 shows the events not associated with GA or IVS reported by all staff, by the dentally qualified staff and by nursing staff over a 10-year period (or for as long as they had been working if less than 10 years). Figure 3 shows the events associated with general anaesthesia reported by dentally qualified staff only. (The data presented is limited to events reported by dental staff in an attempt to minimise double reporting.) The 84 dentists had worked the equivalent of 319.5 years of full time (10 sessions a week) clinical practice over a 10-year period and reported a total of 588 emergency events not including those associated with GA. This represents an average of 1.8 events per year.

Table 1 compares the relative frequency of emergency events reported by dentally qualified staff only, in different disciplines of dental hospital practice, namely restorative dentistry, paediatric dentistry/orthodontics, dental diagnostic science (comprising oral medicine, pathology and radiology), and oral and maxillofacial surgery.

Training

Table 2 shows the number and percentage of dentally qualified and ancillary staff who reported having received training in the management of medical emergencies before and since qualification. Figure 4 shows the components of this training and Figure 5 shows their perceptions of readiness to manage medical emergencies at qualification and currently. In all, 93.0% of respondents expressed a desire for some form of further training to improve their readiness to manage medical emergencies. The majority (88.0%), thought their readiness could be improved by 'hands on' courses and 32.9% expressed a desire for lectures as well. Only 2.5% felt they did not need to improve their readiness.

Discussion

This is the first survey which has attempted to investigate the prevalence of medical emergencies at a dental hospital in the UK. The response, 82% in this survey, is considered to be 'good'.6 However, any survey which seeks to quantify the occurrence of faints or other medical emergencies is prone to inaccuracy resulting from vagaries of memory. Respondents were asked to report emergency events experienced over a 10-year period and faints over a 12-month period in the hope that the effect of defective recollection would be reduced. The data presented rely solely on respondents' ability to remember events which may or may not have actually occurred in the time periods requested. Specific numbers should be interpreted with some caution, especially in consideration of events recalled over a 10-year period. It may also be that some events occurred at the Dental Hospital but went unreported in the survey, as the people who witnessed the event may no longer be working there. Conversely, when considering the total numbers of reported events, a single emergency event could well have been reported by more than one respondent, as true for GA events as for any others. All this notwithstanding, these figures do provide the first broad estimates of the prevalence and relative frequency of different types of medical emergency in this setting, and the training and attitudes of the personnel who attended them.

Fainting is a frequent event in dental practice and in general seems to be well managed, as there are few reports of untoward sequelae. Exactly how often this event occurs is not known but an attempt has been made here to quantify the frequency of its occurrence in a dental hospital setting. Bearing in mind what has been said above, the frequency of faints is quite high and fainting is easily the most common medical emergency event experienced by those surveyed. Two surveys carried out in the US, reported 15,407 faints experienced by 4,309 dentists over a 10-year period, an average of nearly 0.4 faints per dentist per year.7,8 This survey found a ten times greater frequency for the occurrence of this event, at four episodes per full time equivalent dentist per annum.

Other types of medical emergency occurred with an average frequency of 1.8 events per full time equivalent dentist per year. This compares with a UK survey of medical emergencies in general dental practice, where the 'average' GDP witnessed an emergency event once every 3.6 to 4.5 years of practice.3 This represents a seven to eight times higher frequency in the hospital setting, yet the relative frequency of different types of medical emergency appears to be similar.

There may be a number of factors contributing to the differences in reported frequency of emergency events. First, as already mentioned, in a dental hospital it is highly likely that a single emergency event will be reported by more than one dentist. Also, there are differences in the population of patients attending a dental hospital compared with those attending general dental practice: patients with a poor state of general health are often referred from practice to a dental hospital for treatment. It is also possible that a higher proportion of surgical treatment is carried out at the Dental Hospital compared with general dental practice. We found that those working in oral surgery encountered more medical emergencies (especially angina pectoris, myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest) and faints than those in other specialities. A survey of GDPs also found that more emergency events were associated with restorative treatment and dento-alveolar surgery than other dental procedures.3 This may reflect a greater physiological and psychological stress experienced by patients undergoing surgical procedures or requiring a local anaesthetic compared with other aspects of dental treatment.

About three-quarters of ancillary and 70% of dentally qualified staff reported having received training in the management of medical emergencies during their undergraduate training. More than 90% of dentally qualified staff had sought such training since qualifying. The figures for the dentally qualified members of staff are not dissimilar from those reported by a sample of GDPs, where 75.2% and 94.8% respectively had received undergraduate and sought postgraduate training in the management of medical emergencies.4 At graduation, 28.8% of the GDP sample felt 'well' or 'fairly well' prepared to manage a medical emergency compared with 16.9% of the dentally qualified staff of the Dental Hospital. Currently, 78.7% of the GDP sample felt 'well' or 'fairly well' prepared to manage a medical emergency compared with 65.4% of the dentally qualified staff of the Dental Hospital. These differences were statistically significant (P = 0.021 and P = 0.003 respectively). Nonetheless, both samples show a marked shift in perceived readiness to manage medical emergencies from graduation to the current situation. There was a desire expressed by more than 90% of both samples for 'hands on' courses to improve readiness to manage medical emergencies.

Several regions now operate schemes where training sessions in the management of medical emergencies and basic life support is provided to general dental practices 'in-house'. For dental undergraduates there is renewed emphasis on learning about the management of medical emergencies and regular practice of resuscitation routines.9 It is important that qualified dental staff and ancillaries working in the dental hospital service also receive co-ordinated programmes of training. The University Dental Hospital of Manchester has addressed this issue by organising CPR courses and lectures on the management of medical emergencies for all clinical and ancillary staff, as well as organising a more highly trained 'crash team' to deal with cardiac arrests. These measures require monitoring to gauge their effectiveness but provide one possible solution for dental hospital personnel.

Conclusions

-

A questionnaire survey has been carried out which has achieved a good response rate of more than 80%.

-

Fainting appears to be quite a common event in dental hospital practice, with a reported frequency of 4.0 occurrences per annum for dentally qualified staff.

-

Other emergency events were reported with a frequency of 1.8 events per year, (assuming a notional ten clinical sessions a week), some six to eight times higher than that reported by a sample of GDPs.

-

The relative proportion of different types of emergency event, however, mirrors that reported in the general dental practice.

-

Oral surgery procedures appeared to be associated with more faints and emergency events than other types of dental treatment.

-

There is a perceived need for further training to improve readiness to manage medical emergencies and a desire among most dental hospital staff for 'hands on' training.

The authors are grateful to all those members of staff of the University Dental Hospital of Manchester who completed the questionnaire.

References

Maintaining standards – guidance to dentists on professional and personal conduct. London: General Dental Council, 1997.

Chapman P J . Medical emergencies in dental practice and choice of emergency drugs and equipment: a survey of Australian dentists. Aust Dent J 1997; 42: 103–108.

Atherton G J, McCaul J A, Williams S A . Medical emergencies in general dental practice in Great Britain. Part 1: their occurrence over a 10-year period. Br Dent J 1999; 186: 72–79.

Atherton G J, McCaul J A, Williams S A . Medical emergencies in general dental practice in Great Britain. Part 3: perceptions of training and competence of general dental practitioners in their management. Br Dent J 1999; 186: 234–237.

Malamed S F . Medical emergencies in the dental office. 4th ed. p2. St Louis, Missouri: Mosby, 1993.

British Dental Journal. Guidelines for acceptable response rates in epidemiological surveys. 1997; 182: 68.

Fast TB, Martin MD, Ellis TM . Emergency preparedness: a survey of dental practitioners. J Am Dent Assoc 1986; 112: 499–501.

Malamed SF . Managing medical emergencies. J Am Dent Assoc 1993; 124: 40–51.

Smales F C, Anderson J, Basker R M, Harrison A, Kramer L D, Macadam T S, McGowan D A, Murray J J . The first five years: the undergraduate dental curriculum. London: General Dental Council, March 1997.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Atherton, G., Pemberton, M. & Thornhill, M. Medical emergencies: the experience of staff of a UK dental teaching hospital. Br Dent J 188, 320–324 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800469

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800469

This article is cited by

-

A quality improvement project to improve the quality of medical emergency aide-mémoires

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

Kreislaufstillstand unter besonderen Umständen

Notfall + Rettungsmedizin (2021)

-

A ten year experience of medical emergencies at Birmingham Dental Hospital

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Kreislaufstillstand in besonderen Situationen

Notfall + Rettungsmedizin (2015)

-

Bridging the gap – vocational trainee to senior house officer: a new induction course

British Dental Journal (2003)