ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Giving and receiving feedback are critical skills and should be taught early in the process of medical education, yet few studies discuss the effect of feedback curricula for first-year medical students.

OBJECTIVES

To study short-term and long-term skills and attitudes of first-year medical students after a multidisciplinary feedback curriculum.

DESIGN

Prospective pre- vs. post-course evaluation using mixed-methods data analysis.

PARTICIPANTS

First-year students at a public university medical school.

INTERVENTIONS

We collected anonymous student feedback to faculty before, immediately after, and 8 months after the curriculum and classified comments by recommendation (reinforcing/corrective) and specificity (global/specific). Students also self-rated their comfort with and quality of feedback. We assessed changes in comments (skills) and self-rated abilities (attitudes) across the three time points.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Across the three time points, students’ evaluation contained more corrective specific comments per evaluation [pre-curriculum mean (SD) 0.48 (0.99); post-curriculum 1.20 (1.7); year-end 0.95 (1.5); p = 0.006]. Students reported increased skill and comfort in giving and receiving feedback and at providing constructive feedback (p < 0.001). However, the number of specific comments on year-end evaluations declined [pre 3.35 (2.0); post 3.49 (2.3); year-end 2.8 (2.1)]; p = 0.008], as did students’ self-rated ability to give specific comments.

CONCLUSION

Teaching feedback to early medical students resulted in improved skills of delivering corrective specific feedback and enhanced comfort with feedback. However, students’ overall ability to deliver specific feedback decreased over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Giving feedback is a critical skill for effective teaching and learning, the “heart of medical education” 1–3. A recent review of the social science literature defined feedback in clinical education as “specific information about the comparison between a trainee’s performance and a standard, given with intent to improve the trainee’s performance” 4. Generally accepted characteristics of effective formative feedback include aspects of structure, content, and format. Structural requirements encompass location, time, and orientation of the learner to the process and to the goal of the process. Ideally, the provider and recipient are allies and operate in a culture of mutual respect, while feedback is co-constructed through loops of dialogue and information and reflective practice 1,5,6. As for the content of feedback, studies have validated that effective feedback is constructive, specific, and non-judgmental 4,7,8. Useful formats for feedback include oral, written, graphic, and video 9–11.

It is desirable for medical students to learn effective feedback skills early in their careers. Medical educators rely on feedback from learners to impel enhancement of educational programs 12. Moreover, the increased emphasis on assessment of professionalism underscores the need for feedback curricula; in a multicenter study, student focus groups identified that receiving training to give and receive effective feedback is necessary for success of a peer evaluation system of professionalism 13,14. However, there are few reported outcomes of curricula to teach feedback to early medical students. In published descriptions of such curricula for residents and faculty 15–19, there remain several open questions about the scope and effectiveness of these curricula. Few studies report improvements in the quality of feedback as a result of these courses, despite data showing that written feedback is quantifiable 9,19,20. We also found scarce data in the medical literature assessing the long-term effects of curricular interventions to teach feedback.

Our research objectives were: to objectively assess students’ feedback skills at three time points (before, immediately after, and 8 months after a curriculum to teach feedback) and to elicit students’ comfort and perceived efficacy at delivering feedback at the same time points.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were the entire class of 141 first-year medical students at a single institution in 2006. All students received the same feedback curriculum. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for all parts of the study, including student participation in surveys and review of anonymous student course evaluations. A consent form provided to all students explained the purpose and methods of the study, and students voluntarily participated in the study by submitting their surveys.

Setting and Curricular Intervention

At our School of Medicine, the inaugural course for first-year medical students is an interdisciplinary, integrated basic science and foundational clinical skills course called “Prologue/Foundations of Patient Care” (“PFPC”). The course spans 8 weeks.

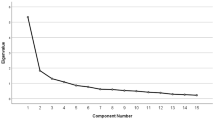

Intervention: In September 2006, we instituted a multidisciplinary curricular module involving anatomy knowledge, clinical skills, and feedback (Figure 1). In the second week of school, students attended an administrative introduction to the use of the online system for school-wide course evaluation, but were not introduced to concepts or principles of feedback. Later that week, students received a lecture about basic principles of feedback. This session defined feedback (emphasizing the important roles of both reinforcing and corrective feedback), its proper setting, structure, content, and formats, and provided in-class case scenarios and practice opportunities. Students were encouraged to continue to practice these skills as they concurrently developed their nascent medical physical examination and interviewing skills in weekly to biweekly small group sessions.

To create a highly integrated setting where students could practice feedback skills relevant to their level of clinical expertise, we created role-play scenarios adapted to the students’ current clinical skills and anatomy knowledge. 6 These role-plays occurred in weeks 5 and 7 of PFPC, immediately after curricular modules on surface anatomy. Students worked in pairs: one student portrayed a patient and read a script of the patient’s concerns, while the other portrayed a physician (without a script) in a clinical vignette highlighting surface anatomy objectives that they had just learned. After the exercises, we asked “patients” to give feedback to “physicians” about their interviewing and physical examination techniques, while “physicians” were asked to self-reflect on their performance. The feedback was structured using a checklist and required a written comment about the encounter. No subsequent formal teaching or reinforcement of feedback principles occurred for the remainder of the school year, although small groups in medical interviewing with actual or standardized patients, coupled with peer feedback, continued on average every other week, for a total of 12 sessions.

Outcome Measures, Evaluation, and Analysis

-

1.

Feedback Skill Assessment

In September 2006, immediately following the administrative introduction of the online evaluation program (PFPC week 2), students were asked to provide online feedback to a lecturer who had taught in PFPC the prior week; these comments comprised qualitative data for time point A. Time point A was open to the whole class. Anonymous online comments collected as part of routine evaluation of course lecturers comprised data for time points B (October 2006, comments on PFPC lecturers) and C (June 2007, comments on lecturers in the final course of the first year, Figure 1). To reduce evaluation fatigue, approximately one-third of each medical school class, selected at random, is assigned to evaluate each medical school course and its lecturers. The online system cues students to complete lecturer evaluations immediately after the lecturer’s series concludes, so that comments are timely and less subject to temporal decay.

-

2.

Self-report of Feedback Skills

In October 2006, after the second series of surface anatomy role-play exercises in week 7 of PFPC, all students were invited to complete a brief self-report survey assessing their attitudes towards giving and receiving feedback using a retrospective pre- and post-intervention survey 21. Students self-reported their abilities on a single retrospective pre-/post-course survey using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree (time points A and B; Figure 1). Students completed the same self-report survey assessing their attitudes towards giving and receiving feedback in June 2007, at the end of their first year (time point C). We calculated descriptive statistics and analyzed changes in self-rated feedback skills with a repeated-measures analysis of variance.

Coding Procedures

Two investigators (MK, CLC) reviewed written student evaluations and coded comments provided to instructors who lectured 3 h or more in the first and last course of the 2006–07 academic year. Because student comments to lecturers are predominantly formative in nature, we simplified a previously used coding scheme 9 to four classifications of feedback: (1) reinforcing global, (2) reinforcing specific, (3) corrective global, and (4) corrective specific. We defined the term “comment” as a quantifiable item in a student’s evaluation that fit one of the four categories. Thus, one evaluation could contain several comments, even if the evaluation consisted of only one sentence (Table 1).

Qualitative data from time point C were analyzed using open coding, refining the definitions of the initial coding scheme. Subsequently, coders independently classified comments from the two remaining time points using the refined coding scheme and identified and discussed each coding discrepancy until reaching consensus. The first dataset was then re-analyzed using the final coding scheme; discrepancies were discussed until reaching consensus. To ensure that the comments could be consistently categorized, another author (PSOS) was trained to use the coding scheme. She independently rated 32 comments representing a sampling across all faculty for whom written comments were made. The correlation with those scores and those of the primary raters were 0.76 for positive specific comments, 0.92 for negative specifics, 0.67 for global positives and 0.51 for global negatives. The latter score was low due to the very few negative global comments in the sample. This reliability study supports that another reviewer can obtain consistent ratings for counting comments.

The average number of comments per written student evaluation was calculated. Descriptive statistics were calculated using a one-way ANOVA, followed by a Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis of differences between time points A, B, and C.

RESULTS

Feedback skill assessment

The response rate on the evaluations and the number of comments coded are listed in Table 2. The total number of evaluations per faculty member decreased from 29 at time point B to 17.3 at time point C.

The average number of reinforcing global comments across the first two time points remained statistically similar, but increased by year’s end (Table 3). There was a significant decrease in reinforcing specific comments from time point A to B, without further change at time point C. Conversely, corrective specific comments statistically increased from time point A to B, with a sustained change at the end of the year. We were unable to assess a change in corrective global comments, because there were none prior to the exercises. The overall averages of total global and total specific comments remained the same from time point A to time point B; at time point C, total specific comments decreased significantly compared to the two previous time points, whereas total global comments increased compared to the two previous time points.

Student self-assessment

Students’ comfort in giving and receiving feedback from peers increased significantly from time point A to time point B and remained high at time point C (Table 4). Students rated that their feedback was more constructive after the curriculum, and that attitude was sustained 8 months later. On the other hand, students believed that while the specificity of their feedback increased from time point A to time point B, it decreased to levels statistically indistinguishable from pre-curriculum levels at time point C.

DISCUSSION

Our study of the effects of an integrated curricular module on feedback for first-year medical students resulted in the following three findings. (1) Students’ skill at delivering corrective specific comments to faculty in an anonymous written venue increased immediately after the curricular module and remained high after 8 months, and this skill corresponded to their self-assessment that their feedback was more constructive at these time points. (2) The overall specificity of students’ feedback to faculty decreased immediately post-curriculum, contrary to students’ self-assessment; long term, students accurately self-assessed that the specificity of their feedback had declined. (3) Students felt significantly more comfortable giving and receiving peer feedback, both immediately and 8 months after the completion of the module. These findings are consistent with studies showing that teaching feedback to faculty results in short-term increases in specific comments 9,19,22.

We believe this analysis extends what is known about teaching feedback in several substantive ways. Most previous curricular descriptions assessed immediate post-curricular attitudes in small numbers of residents or faculty who chose to undertake specific courses in teaching 23,24; here, we objectively assessed both skills and attitudes in feedback. Our study population was a large class of first-year medical students unselected for their interest in teaching. Moreover, students knew that the feedback they provide to lecturers is anonymous, an important factor influencing the likelihood to participate in providing specific feedback 13,14. Finally, we studied long-term skill retention of our curriculum.

In our study, the observed fall in the overall specificity of students’ feedback appeared to apply wholly to their delivery of reinforcing comments, since their frequency of corrective specific comments remained statistically significantly higher than baseline. Interestingly, as the average number of reinforcing specific comments fell, there was a corresponding rise in reinforcing global comments. High levels of comfort giving and receiving feedback may reflect a high degree of unconditional support and praise for classmates. This supposition is consistent with a study reporting that the ratio between reinforcing and corrective comments provided to peers was four to one 25.

The increase in corrective specific comments is consistent with prior studies that noted short-term increases or no change in written specific feedback comments 9,19. Our study adds that students retained these skills for at least 8 months. The reduced number of reinforcing specific comments we observed could indicate that our curriculum emphasized corrective over supportive feedback or the development of “evaluation fatigue” rather than an actual decrement in skills. Indeed, compared with a 100% response rate on evaluations at time point B, only 74% of students completed evaluations at time point C. Alternatively, the anonymous nature of the evaluations may have increased critical appraisals of faculty 26. Specific appreciative comments have been shown to enhance significant cultural change at a medical school through participants’ heightened awareness of relational capacity 27; therefore, it may be desirable to change our curricular module to further highlight the utility and skill of reinforcing specific feedback, rather than merely corrective feedback.

There is considerable literature showing that self-assessments by physicians, residents, and medical students at all levels are inaccurate 25,28–30. Similar but limited data exist for self-assessment of feedback skills: general practitioners in training report being capable of giving feedback, while objective review indicates that their skills need improvement 31. Our first-year students erroneously assessed the overall change in specificity of their feedback by time point B, but accurately reported at time point C that their feedback was less specific and more constructive. Students may have favored the importance of corrective comments when asked to rate their own feedback skills; however, further studies are required to test this assumption. Additionally, accuracy in self-assessment may be related to students’ familiarity with the task at hand 32; they may have had more experience using specific language for constructive, rather than reinforcing, comments.

Our finding that students can show long-term improvement of feedback skills reflects prior data in faculty development. Thirty-two participants reported increased feedback skills as long as 14 years after completion of a faculty development program 23; this study did not provide data on feedback quality. In a recent review examining long-term retention of basic science knowledge, several principles emerged, including reinforcement, prolonged contact with a domain, and structured revisitation over time 33. It is possible that these factors also apply to retention of feedback skills: as our students progressed through the remainder of their first year of medical school, they continued to practice feedback in discussion groups and to complete online evaluations of their instructors.

Our study appears to be one of the first to objectively analyze the characteristics of students’ evaluations of instructors. One prior analysis of evaluations in a problem-based learning curriculum noted that faculty recipients of students’ written feedback valued the specific directions students offered for improvement 34. Other reports demonstrated that most faculty in health sciences and other disciplines use written feedback from students to improve the effectiveness of their teaching 35,36. Future studies will need to assess if and how instructors differentially change their teaching behaviors in response to the reinforcing/constructive and global/specific nature of students’ comments.

There are limitations to this study. First, analysis occurred in a single school, in a single class of students. Second, though our curriculum taught students to give both oral and written feedback to peers, we measured the specificity of their written anonymous feedback to faculty. We maintain these are the same or highly analogous skills: the ability to compose a feedback statement should meet the general principles in oral or written settings 8,37. Third, the generalizability of our results might be affected by sampling bias. We believe that our school’s evaluation system attempts to balance evaluation fatigue with self-selection bias; however, it is still possible that the students’ skill levels demonstrated in this study are not fully representative of the entire class. Finally, our study examined objective analysis of students’ skill in writing comments, without determining the impact of those comments on the intended recipient; therefore, we have measured and reported just one aspect of feedback, and not its ultimate efficacy.

In summary, we found that teaching feedback in an integrated curriculum to first-year medical students resulted in immediate and long-term improvement in comfort giving and receiving feedback, and skills of delivering corrective specific feedback. Moreover, students were able to conduct accurate long-term self-assessments of the constructiveness of their feedback. Further studies could address how to expand the acquisition and retention of feedback skills to include specific reinforcing feedback, and to determine factors that influence long-term retention of feedback skills. Ultimately, assessing the impact of student comments on the intended recipient will determine the true efficacy of such curricula.

References

Bienstock JL, Katz NT, Cox SM, Hueppchen N, Erickson S, Puscheck EE. To the point: medical education reviews–providing feedback. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(6):508–13.

Branch WT, Paranjape A. Feedback and reflection: teaching methods for clinical settings. Acad Med. 2002;77(12):1185–8.

Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250(6):777–81.

van de Ridder JMM, Stokking KM, McGaghie WC, ten Cate OTJ. What is feedback in clinical education. Med Educ. 2008;42(2):189–97.

Askew S, Lodge C. Gifts, ping-pong and loops - linking feedback and learning. In: Askew S, ed. Feedback for Learning. London: Routledge/Falmer; 2000:1–17.

Cole KA, Barker LR, Kolodner K, Williamson P, Wright SM, Kern DE. Faculty development in teaching skills: an intensive longitudinal model. Acad Med. 2004;79(5):469–80.

Hewson MG, Little ML. Giving feedback in medical education: verification of recommended techniques. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(2):111–6.

Shute V. Focus on formative feedback. Rev Educ Res. 2008;78(1):153–89.

Salerno SM, Jackson JL, O’Malley PG. Interactive faculty development seminars improve the quality of written feedback in ambulatory teaching. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(10):831–4.

Kogan JR, Bellini LM, Shea JA. Have you had your feedback today. Acad Med. 2000;75(10):1041.

Regan-Smith M, Hirschmann K, Iobst W. Direct observation of faculty with feedback: an effective means of improving patient-centered and learner-centered teaching skills. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(3):278–86.

Kern DE, Thomas PA, Howard DM, Bass EB. Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2000.

Shue CK, Arnold L, Stern DT. Maximizing participation in peer assessment of professionalism: the students speak. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 Suppl):S1–5.

Arnold L, Shue CK, Kalishman S, Prislin M, Pohl C, Pohl H, Stern DT. Can there be a single system for peer assessment of professionalism among medical students? A multi-institutional study. Acad Med. 2007;82(6):578–86.

Spickard A III, Corbett EC Jr, Schorling JB. Improving residents’ teaching skills and attitudes toward teaching. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11(8):475–80.

Salerno SM, O’Malley PG, Pangaro LN, Wheeler GA, Moores LK, Jackson JL. Faculty development seminars based on the one-minute preceptor improve feedback in the ambulatory setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(10):779–87.

Morrison EH, Rucker L, Boker JR, Gabbert CC, Hubbell FA, Hitchcock MA, Prislin MD. The effect of a 13-hour curriculum to improve residents’ teaching skills: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(4):257–63.

Haber RJ, Bardach NS, Vedanthan R, Gillum LA, Haber LA, Dhaliwal GS. Preparing fourth-year medical students to teach during internship. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):518–20.

Holmboe ES, Fiebach NF, Galaty L, Huot S. The effectiveness of a focused educational intervention on resident evaluations from faculty: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(7):427–34.

Sluijsmans DMA, Brand-Gruwel S, Van Merriënboer JJG. Peer assessment training in teacher education. Assessment Eval Higher Educ. 2002;27(5):443–54.

Internal invalidity in pretest-posttest self-report evaluations and a re-evaluation of retrospective pretests. Appl Psychol Meas. Howard GS; 1979;3(1):1–23.18.

Berbano EP, Browning R, Pangaro L, Jackson JL. The impact of the Stanford faculty development program on ambulatory teaching behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):430–4.

Knight AM, Carrese JA, Wright SM. Qualitative assessment of the long-term impact of a faculty development program in teaching skills. Med Educ. 2007;41(6):592–600.

Menachery EP, Knight AM, Kolodner K, Wright SM. Physician characteristics associated with proficiency in feedback skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):440–6.

Rudy DW, Fejfar MC, Griffith CH 3rd, Wilson JF. Self- and peer assessment in a first-year communication and interviewing course. Eval Health Prof. 2001;24(4):436–45.

Afonso NM, Cardozo LJ, Mascarenhas OA, Aranha ANF, Shah C. Are anonymous evaluations a better assessment of faculty teaching performance? A comparative analysis of open and anonymous evaluation processes. Fam Med. 2005;37(1):43–7.

Suchman AL, Williamson PR, Litzelman DK, Frankel RM, Mossbarger DL, Inui TS. Relationship-centered care initiative discovery team toward an informal curriculum that teaches professionalism: transforming the social environment of a medical school. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(5 Pt 2):501–4.

Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1094–102.

Srinivasan M, Hauer KE, Der-Martirosian C, Wilkes M, Gesundheit N. Does feedback matter? Practice-based learning for medical students after a multi-institutional clinical performance examination. Med Educ. 2007;41(9):857–65.

Langendyk V. Not knowing that they do not know: self-assessment accuracy of third-year medical students. Med Educ. 2006;40(2):173–9.

Prins FJ, Sluijsmans DMA, Kirschner PA. Feedback for general practitioners in training: Styles, quality and preferences. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2006;11(3):289–303.

Fitzgerald JT, White CB, Gruppen LD. A longitudinal study of self-assessment accuracy. Med Educ. 2003;37(7):645–9.

Custers EJFM. Long-term retention of basic science knowledge: a review study. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2008; published ahead of print; doi: 10.1007/s10459-008-9101-y. Latest date of access 3/31/09.

van Wyk JM, McLean M. Maximising the value of feedback for individual facilitator and faculty development. Med Teach. 2007;26(1):e26–31.

Schum TR, Yindra KJ. Relationship between systematic feedback to faculty and ratings of clinical teaching. Acad Med. 1996;71(10):1100–2.

Yao Y, Weissinger E, Grady M. Faculty use of student evaluation feedback. Pract Assess, Res Eval. 2003;8(21). Retrieved March 9, 2009 from http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=8&n=21.

Elnicki MD, Layne RD, Ogden PE, Morris DK. Oral versus written feedback in medical clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(3):155–8.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joseph Crawford and Melissa Salonga for their invaluable support with survey data collection, Josephine Tan for her help with literature searches, and UCSF medical students for their cooperation.

Disclosure conflict of interest and funding sources

None of the authors has a conflict of interest, and no external or internal funding resources contributed to completion of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An abstract of this study was presented at a poster session at the AAMC Annual Meeting, Washington DC, November 2007.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kruidering-Hall, M., O’Sullivan, P.S. & Chou, C.L. Teaching Feedback to First-year Medical Students: Long-term Skill Retention and Accuracy of Student Self-assessment. J GEN INTERN MED 24, 721–726 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-0983-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-0983-z