Abstract

Background

Postoperative outcome of patients is determined by recovery characteristics and self-reported quality of life. The first can be assessed with the McPeek score which values three aspects of recovery: mortality, postoperative critical care and duration of hospitalization.

Materials and methods

We calculated the McPeek score of 669 patients in three trials: (1) colorectal cancer surgery, (2) antihistamine/volume loading in various operations, and (3) cholecystectomy. Beforehand, the average of intensive care unit treatment and duration of hospitalization were determined for the different operations to define McPeek score points. The score was tested on reliability, validity, and sensitivity. In addition, clinical applicability was assessed in a survey.

Results

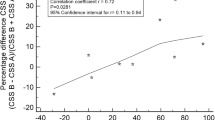

The score was reliable with similarly distributed score points in the three trials at different institutions. Inter-rater reliability was high (97% overlap). Validity was proven by moderate high correlation to convergent criteria such as complications (trial I to III r=0.43, r=0.38, r=0.60), preoperative American Society of Anesthesiologists class (ASA) (r=0.24, r=0.28, r=0.57), and age (r=0.23, r=0.32, r=0.31). The score was different between patients with and without neoplasms (P<0.001, trial II) and between elective or emergency patients (P<0.001, trial III). In a survey, investigators reported that the score was easy to assess and more comprehensive than four other scores.

Conclusions

The McPeek score values the postoperative outcome on a nonlinear scale. A priori, the average duration of hospitalization and critical care for a specific operation has to be defined. Our validation suggests that it is a reliable, valid, sensitive, and practical instrument for outcome analysis after anesthesia and surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sheridan WG, Williams HO, Lewis MH (1987) Morbidity and mortality of common bile duct exploration. Br J Surg 74:1095–1099

Vironen JH, Halme L, Sainio P, Kyllonen LE, Scheinin T, Husa AI, Kellokumpu IH (2002) New approaches in the management of rectal carcinoma result in reduced local recurrence rate and improved survival. Eur J Surg 168:158–164

Basse L, Hjort JD, Billesbolle P, Werner M, Kehlet H (2000) A clinical pathway to accelerate recovery after colonic resection. Ann Surg 232:51–57

Smith RL, Bohl JK, McElearney ST, Friel CM, Barclay MM, Sawyer RG, Foley EF (2004) Wound infection after elective colorectal resection. Ann Surg 239:599–605

Ruland CM, Bakken S (2002) Developing, implementing, and evaluating decision support systems for shared decision making in patient care: a conceptual model and case illustration. J Biomed Inform 35:313–321

Wolters U, Wolf T, Stützer H, Schröder T (1996) ASA classification and perioperative variables as predictors of postoperative outcome. Br J Anaesth 77:217–222

Cullen DJ, Civetta JM, Briggs BA, Ferrara L (1974) Therapeutic intervention scoring system: a method for quantitative comparison of patient care. Crit Care Med 2:57–60

McPeek B, Gasko M, Mosteller F (1986) Measuring outcome from anesthesia and operation. Theor Surg 1:2–9

Jenicek M (1995) Prognosis. Studies of disease course and outcome. In: Jenicek M (ed) Epidemiology, the logic of modern medicine. EPIMED, New Haven, Connecticut, pp 241–266

Lorenz W, Duda D, Dick W, Sitter H, Doenicke A, Black A, Weber D, Menke H, Stinner B, Junginger T, Rothmund M, Ohmann C, Healy MJR, The Trial Group Mainz/Marburg (1994) Incidence and clinical importance of perioperative histamine release: randomised study of volume loading and antihistamines after induction of anaesthesia. Lancet 343:933–940

Ludwig K, Patel K, Wilhelm L, Bernhardt J (2002) Prospective study on patients outcome following laparoscopic vs. open cholecystectomy. Zentralbl Chir 127:41–46

Nies C, Krack W, Lorenz W, Kaufmann T, Sitter H, Celik I, Rothmund M (1997) Histamine release in conventional vs minimally invasive surgery: results of a randomised trial in acute cholecystitis. Inflamm Res 46(Suppl 1):S83–S84

Lohr KN, Aaronson NK, Alonso J, Burnam MA, Patrick DL, Perrin EB, Roberts JS (1996) Evaluating quality-of-life and health status instruments: development of scientific review criteria. Clin Ther 18:979–992

Lorenz W, Dick W, Junginger T, Ohman C, Ennis M, Immich H, McPeek B, Dietz W, Weber D (1988) Induction of anaesthesia and perioperative risk: influence of antihistamine H1+H2-prophylaxis and volume substitution with Haemaccel-35 on cardiovascular and respiratory disturbances and histamine release. Protocol of a controlled clinical trial. Theor Surg 3:55–77

Elebute EA, Stoner HB (1983) The grading of sepsis. Br J Surg 70:29–31

Myles PS, Weitkamp B, Jones K, Melick J, Hensen S (2000) Validity and reliability of a postoperative quality of recovery score: the QoR-40. Br J Anaesth 84:11–15

Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JEJ (1995) Methods of validating MOS health measures. In: Stewart AL and Ware JEJ (eds) Measuring functioning and well-being. Duke Univ. Press, Durham, North Carolina, pp 309–324

Lorenz W (1998) Outcome: definition and methods of evaluation. In: Troidl H, McKneally MF, Mulder DS, Wechsler AS, McPeek B, Spitzer WO (eds) Surgical research: basic principals and clinical practice, 3rd edn. Springer, New York Berlin Heidelberg, pp 513–520

McDowell I, Newell C (1996) Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires. Oxford Univ. Press, New York, USA

Wood-Dauphinee S, Troidl H (1989) Assessing quality of life in surgical studies. Theor Surg 4:35–44

Sitter H, Stinner B, Duda D, Menke H, Lorenz W (1995) Model building strategies for risk analysis of perioperative histamine-related cardiorespiratory disturbances. Inflamm Res 44:S82–S83

Menke H, Graf JM, Heintz A, Klein A, Junginger T (1993) Risk factors of perioperative morbidity and mortality in colorectal cancer with special reference to tumor stage, site and age. Zentralbl Chir 118:40–46

Hall JC, Hall JL (1996) ASA status and age predict adverse events after abdominal surgery. J Qual Clin Pract 16:103–108

Cullen DJ, Apolone G, Greenfield S, Guadagnoli E, Cleary P (1994) ASA physical status and age predict morbidity after three surgical procedures. Ann Surg 220:3–9

Menke H, Klein A, John KD, Junginger T (1993) Predictive value of ASA classification for the assessment of the perioperative risk. Int Surg 78:266–270

McDowell I, Newell C (1996) Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires. Oxford Univ. Press, New York

Donabedian A (1966) Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q 44:166–203

Torrance GW, Feeny D (1989) Utilities and quality-adjusted life years. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 5:559–569

Atherly A, Culler SD, Becker ER (2000) The role of cost effectiveness analysis in health care evaluation. Q J Nucl Med 44:112–120

Lorenz W, Troidl H, Solomkin JS, Nies C, Sitter H, Koller M, Krack W, Roizen MF (1999) Second step: testing–outcome measurements. World J Surg 23:768–780

Koller M, Lorenz W (2002) Quality of life: a deconstruction for clinicians. J R Soc Med 95:481–488

Bauhofer A, Lorenz W, Stinner B, Rothmund M, Koller M, Sitter H, Celik I, Farndon JR, Fingerhut A, Hay J-M, Lefering R, Lorijn R, Nyström P-O, Schäfer H, Schein M, Solomkin J, Troidl H, Volk H-D, Wittmann DH, Wyatt J, Lucerne Group for Consensus-assisted Development of the Study Protocol on Prevention of Abdominal Sepsis: Example G-CSF (2001) Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor in the prevention of postoperative infectious complications and sub-optimum recovery from operation in patients with colorectal cancer and increased preoperative risk (ASA 3 and 4). Protocol of a controlled clinical trial developed by consensus of an international study group. Part two: design of the study. Inflamm Res 50:187–205

Nies C, Celik I, Lorenz W, Koller M, Plaul U, Krack W, Sitter H, Rothmund M (2001) Outcome of minimally invasive surgery. Qualitative analysis and evaluation of the clinical relevance of study variables by the patient and physician. Chirurg 72:19–28

Bauhofer A, Lorenz W, Stinner B (2004) Improvement of quality of life by G-CSF prophylaxis in high risk patients with colorectal cancer surgery—results of a randomised trial. Shock 21:39 (Suppl)

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergmann B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ (1993) The European Organisation for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality of life instrument fore use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:356–376

Moller JT, Cluitmans P, Rasmussen LS, Houx P, Rasmussen H, Canet J, Rabbitt P, Jolles J, Larsen K, Hanning CD, Langeron O, Johnson T, Lauven PM, Kristensen PA, Biedler A, van Beem H, Fraidakis O, Silverstein JH, Beneken JE, Gravenstein JS (1998) Long-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly ISPOCD1 study. ISPOCD investigators. International Study of Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction. Lancet 351:857–861

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BA 1560-2/4). We thank Carmi Margolis M.D. (professor of Pediatrics, University Beer Sheva, Israel) for discussing the paper with us, Martin Middeke M.D. (Institute of Theoretical Surgery, University of Marburg) for creating the database, and Helen Prünte (mathematician, Institute of Theoretical Surgery, Marburg, Germany) for statistical calculations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: The McPeek recovery score

| Score points |

Patient who died: | |

– in the operating theatre | 1 |

– in the hospital, but after leaving the operating theatre | 2 |

Patient who was discharged alive: | |

– required a great amount of care after operation in an ICU | 4 |

– required a moderate amount of care after operation in an ICU | 5 |

Patient with a routine recovery: | |

– had a relatively long postoperative hospitalization | 7 |

– had an average postoperative hospitalization | 8 |

– had a relatively short postoperative hospitalization | 9 |

This score is non-additive; points are assigned on the basis of the most severe event. Patients with optimal recovery were thus given a score of 9. A great amount of care after operation was defined as three or more days on an intensive care unit and a moderate amount of less then three days. A relatively long duration of hospitalization was defined as >17 days in trial I and >12 days in trials II and III, an average duration was 14–17 days in trial I and 8–12 days in trials II and III, and a relatively short duration as <14 days in trial I and <8 days in trials II and III.

Appendix 2: Instruction for determination of the McPeek score

Steps for McPeek classification | Example: trial III |

A) Identification of the operations of interest | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

B) Determination of: | |

ICU amount (range) | 0–3 days |

Determination of actual duration of hospitalization (range) for the selected operation | 3–10 days |

C) Defining ICU treatment as: | |

Great (4 score points) | >2 ICU days |

Moderate (5 score points) | 1–2 ICU days |

Defining duration of hospitalization | |

Long (7 score points) | >12 days |

Average (8 score points) | 12–8 days |

Short (9 score points) | <8 days |

D) Classification of the patients as defined in step C | 2 patients, 2 score points |

6 patients, 4 score points | |

12 patients, 5 score points | |

9 patients, 7 score points | |

18 patients, 8 score points | |

31 patients, 9 score points |

This score is non-additive; points are assigned on the basis of the most severe event. For example, mortality in the operating theatre is always 1 score point and mortality in the postoperative follow-up period of 30 days is 2 score points.

Appendix 3

A) Definitions of postoperative complications (trial I and III) | |

Pulmonary dysfunction | Pneumonia, atelectasis, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, embolism—if followed by a therapeutic intervention |

Thrombo-embolism | Clinical signs, phlebography, or scintigraphy |

Cardiac dysfunction | Heart failure, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction—if followed by a therapeutic intervention |

Renal dysfunction | Anuria, increase in serum creatinin >1.5 mg/dl or increase of >0.5 mg/dl in patients with preoperative increased levels |

Liver dysfunction | Icterus, increase in bilirubin <1.2 mg/dl or trans-aminases >30% of standard value |

Pancreatic dysfunction | S-Amylases >250 mg/dl |

Wound infection | Visible pus |

Anastomotic leakage (peritonitis) | Clinical signs±purulent or fecal drainage |

Ileus | Missing bowel peristalsis >4 days, X-ray signs |

Sepsis | Proven infection and 2 of the 4 SIRS criteria: |

Temperature >38 or <36°C | |

Heart rate >90 beats/min | |

Respiratory rate >20 breaths/min | |

White blood cell count >12,000 cells/ml or <4,000 cells/ml | |

B) Responses to intraoperative events/complications (trial II) | |

Pulmonary | Hyperventilation (volume, oxygen), fenoterol inhalation, theophylline, endotracheal suction |

Cardiac | Vasopressors, volume loading (faster or more), head down position, reduction of enflurane, atropine |

Allergic | Corticosteroids, anti-histamines, theophylline, epinephrine |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bauhofer, A., Lorenz, W., Koller, M. et al. Evaluation of the McPeek postoperative outcome score in three trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg 391, 418–427 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-005-0020-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-005-0020-6