Abstract

Background and Objectives Although anoxic encephalopathy is the most dreaded consequence of submersion accidents, respiratory involvement is also very common in these patients. Nevertheless, few data are available about the clinical course and resolution of lung injury in adult victims of near-drowning. Our goal was to study the clinical manifestations of near-drowning and the course of respiratory involvement in a retrospective cohort of adult, mostly elderly patients. Patients Our study included adult patients who were hospitalized after near-drowning in seawater over an 8-year period. Forty-three patients (26 female, 17 male), with an age range of 18–88 years old, were studied. Most (79%) of the patients were elderly (>60 years). Results In the Emergency Department two patients were comatose and required intubation. Another patient was intubated within the first 24 h because of ARDS. At presentation, all patients but two had a PaO2/FiO2 < 300, while ARDS was present in 17 and acute lung injury in 15 cases. The nine remaining hypoxemic patients had either focal infiltrates or a negative chest X-ray. Superimposed pneumonia was observed in four patients and resulted in a protracted hospital stay. Improvement of lung injury was rapid in most cases: by day 4 resolution of hypoxemia was observed in 33/43 (76.7%) of the cases and resolution of radiographic findings in 66.6%. Duration of hospitalization varied from 2 to 14 days (mean = 5.2 ± 0.5 days). One patient with coma died due to ventilator-associated pneumonia (mortality = 2.3%). Conclusion Respiratory manifestations of near-drowning in adult immersion victims are often severe. Nevertheless, in noncomatose patients at least, intubation can often be avoided and quick improvement is the rule while a good outcome is usually expected even in elderly patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drowning is the third most common cause of accidental death, with the majority of drowning victims being younger than 20 years [1]. Although the outcome of patients after accidental submersion in a liquid medium is related mainly to the presence or absence of anoxic encephalopathy, acute respiratory failure (ARF) is also very common in these patients [2–4]. We report our experience with hospitalized victims of submersion in warm seawater, who survived for at least 24 h after the accident, with special emphasis on the respiratory consequences of submersion. We also describe the time-frame of the resolution of radiographic findings and the recovery of pulmonary gas exchange. Although definitions for submersion injury are by no means uniform [5], we have kept in our discussion the time-honored term “near-drowning” as defined by Model [6] in order to characterize our cohort.

Material and Methods

We reviewed the medical records of all submersion victims admitted to the Pulmonary Department of a general hospital serving a suburban area of Athens in close proximity to the coastline, during a period of 8 years (1994–2002). Patients who expired within the first 24 h were excluded. Recorded data included demographics, underlying diseases, swimming experience, mental status (using the Conn–Barker scoring system [7]), arterial blood gases (ABGs), chest X-ray, and laboratory data on admission to the hospital. We also recorded duration of hospital stay, presence or absence of secondary complications such as pneumonia, and the time-frame of resolution/recovery of gas exchange and radiographic findings. Chest X-rays were reviewed by two pulmonologists-intensivists with respect to the pattern and extent of parenchymal opacities and decision was reached by consensus. Respiratory involvement with hypoxemia and diffuse infiltrates was designated as either acute lung injury (ALI) or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) based on the American–European Consensus Conference [8].

Resolution of hypoxemia was defined as having a PaO2 > 60 mmHg without supplemental oxygen. Resolution of radiologic findings was defined as the characterization of the chest X-ray as negative by both reviewers.

Numerical variables are expressed as mean (SD) or median and interquartile range. The normality of distributions was assessed by visual inspection of plots and a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Comparisons of numerical variables were performed using the t test or the Mann–Whitney U test. Qualitative characteristics are reported as percentages (%) and analyzed using the χ2 test. Associations were examined using either Pearson or Spearman correlation (depending on the type of distribution). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism ver. 3.03 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Results

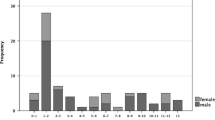

A total of 43 cases (17 male, 26 female) of near-drowning were admitted over a period of 8 years. Median age was 69.2 years (interquartile range = 62–80), with 34 patients older than 60. Seventeen patients (39.5%) had a history of preexisting chronic health problems (10 cardiovascular, 4 diabetes mellitus, 1 rheumatoid arthritis, 1 asthma, 1 epilepsy). All cases resulted from accidental submersion during recreational swimming in seawater during the summer months. All survivors stated that they were experienced swimmers. The accident was preceded by procardial pain (2 cases), seizure attack (1 case), acute alcohol intoxication (1 case), and self-reported dizziness (8 patients). In all cases there were no data for the duration of submersion before rescue. There were no coexisting injuries (e.g., head or spine).

At the scene of rescue, 10 patients were comatose and 6 more had varying degrees of confusion. Half of the patients regained consciousness rapidly after initial resuscitation at the scene, and on admission the Conn–Barker [6] scale was A (awake) in 34 cases, B (blunted) in 7, and C (comatose) in 2 (one patient was C1 and the other was C2). The two comatose scale C patients were intubated at the ED on arrival. Another patient required intubation a few hours later because of respiratory failure and ARDS. On admission, two patients had mild hypothermia and seven additional patients had an axillary temperature higher than 37.3°C (up to 38.2°C).

Data on ABGs and laboratory values are given in Table 1. PaO2/FiO2 significantly correlated with the level of consciousness on admission (rs = 0.48, p = 0.003), serum sodium (rs = −0.42, p = 0.014), and white blood cell count (WBC) (rs = −0,43, p = 0.002) but not with age.

A chest X-ray was obtained for all patients shortly after arrival. Thirty-four patients had bilateral diffuse infiltrates (radiographic findings suggesting pulmonary edema). More data on these patients are presented in Table 2. In addition, five patients had localized alveolar infiltrate (lobar or segmental) with concomitant hypoxygenemia, while a low PaO2/FiO2 with normal chest X-ray was found in four cases. Other chest X-ray findings (sand bronchogram, Kerley lines, pleural effusion) were absent.

Criteria for ALI were fulfilled in 17 cases and criteria for ARDS in 15 cases. Furthermore, 2 of the 34 patients with diffuse bilateral infiltrates had a PaO2/FiO2 > 300.

Intubated patients (2 with coma and 1 with ARDS) were transferred to the ICU. Two of them were successfully extubated within 48–96 h. The patient with a Conn–Barker score of C3 [6] had no neurologic improvement and died 3 weeks later due to ventilator-associated pneumonia, sepsis, and multiple organ failure syndrome. A fourth nonintubated patient, who was also admitted to the ICU for acute respiratory failure, was successfully managed with noninvasive positive ventilation (NIPPV).

All patients on spontaneous ventilation were treated with furosemide and administration of supplemental O2. Steroids were not administered. All patients received chemoprophylaxis with intravenous antibiotics (amoxicillin or cefuroxime).

Presumed pneumonia (new onset of fever >38.3°C) with new and persistent focal radiographic infiltrates complicated the clinical course in four patients, one of whom required intubation. In all cases pneumonia was a late complication (>4 days). Klebsiella pneumoniae was isolated from the mechanically ventilated patient. In all other cases no pathogen was isolated. All nonintubated patients with clinical suspicion of pneumonia had rapid clinical improvement with an empirical change in antibiotic regimen.

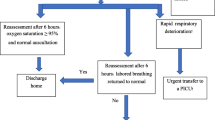

In most cases there was a rapid improvement in PaO2/FiO2 within the first 24 h (from 214 ± 59 mmHg to 250 ± 66 mmHg, p = 0.004). Resolution of hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2 > 300 and PaO2 > 60 mmHg without supplemental oxygen) was observed by day 4 in 33/43 (76.7%) of the cases (Fig. 1). Delayed resolution (after first week) of hypoxemia was observed in three cases due to pneumonia (Fig. 1).

Resolution of radiographic findings was observed by day 4 (Fig. 1) in 26/39 (66.6%) of the cases and by day 7 in 34/39 (87.2%). Delayed resolution (after first week) of chest X-ray was observed in five cases, in three of which it was due to the development of pneumonia.

Patients were discharged after 2–15 days (mean stay = 5.2 ± 0.5 days). Duration of hospital stay was significantly longer in patients who had an affected level of consciousness (confusion or coma) (7.6 ± 0.8 vs. 4.3 ± 0.8 days, p = 0.023). There was no significant association between duration of hospital stay and age, PaO2/FiO2, and presence of chronic underlying conditions. In-hospital mortality was 2.3% (1/43).

Discussion

The present study reports on a retrospective cohort of 43 cases of near-drowning in warm seawater. In contrast to most reports on near-drowning, our series included only adults, with the majority being older than 60. According to a large series on near-drowning, the mortality of victims is about 9–12%, without significant differences between freshwater and seawater drowning [9, 10]. The primary variable influencing outcome is the neurologic status of the patient, with patients admitted with a blunted conscience having a worse outcome than patients who are alert, and with comatose patients faring worse than all the others [10–13].

Although some previous series on near-drowning also included some elderly patients [9, 11, 14], data are sparse on the outcome of this group. Model et al. [11] state that age did not seem to influence the outcome, but it seems that in their study only a few patients were elderly.

With a mortality of 2.3%, our cohort confirms that patients of near-drowning who have good neurologic status after initial resuscitation usually have a good prognosis, in spite of old age, presence of ARF, or comorbidities. Although we do not have detailed data on the patients’ state at the rescue site, most of them probably corresponded more or less to grade 2–3 severity according to the stratification of Spilzman et al. [10]. The expected mortality in such patients is reported to be 0.6–5.2% [10], not much different from that observed in our study. Yet their large cohort included much younger patients (mean age = 22.7 ± 11.5) than our series.

While commonly reported causes of secondary submersion injury (alcohol or drug abuse, seizure attack, trauma) [15] were unusual in our study, many of our patients complained of a nonspecific dizziness just before the accident. Given the advanced age of most of our patients, this may have been related to rhythm disturbances or transient cerebral or coronary ischemia, but in most cases we had no sufficient evidence to substantiate this hypothesis.

Contrary to what is known about the epidemiology of submersion injury [1], most victims in our cohort were female. A possible explanation may be that in the elderly, differences between the sexes with respect to propensity to danger-prone behavior probably become attenuated.

Despite the low incidence of neurologic impairment in our study, all our patients had respiratory involvement, in many cases severe. We did not find a significant correlation between PaO2/FiO2 and age in our study. Increased sodium and WBC were negatively associated with oxygenation and they probably represent indices of more severe immersion injury.

Chest X-ray findings were similar to those reported in the literature but the incidence of pulmonary edema was higher in our patients [16, 17]. The asymmetry of radiographic findings observed in some of our patients has been noticed by others as well and it has been attributed to body position [17]. The fact that we found right lung predominance in cases of asymmetry should probably be attributed to more water being aspirated in the right lung. We also observed some cases of focal consolidation, presumably because of localized aspiration. In agreement with previous reports [16, 18], we found rapid chest X-ray improvement in uncomplicated cases, with persistence of infiltrates for more than 10 days suggesting complications (pneumonia).

Although late ARDS has rarely been reported to develop in initially asymptomatic patients with normal chest X-ray at presentation [19], no such cases were seen in our series. In agreement with previous reports, some patients had hypoxemia with a normal chest X-ray, but in all patients who developed ALI or ARDS, radiographic findings suggestive of pulmonary edema were already present in the first few hours [20]. In all patients without supervening pulmonary infection, a steady improvement in chest X-ray was observed after the first 24 h.

Almost one-third of our patients fulfilled the criteria for ARDS. Nevertheless, only one of them had to be intubated because of respiratory failure. Previous series report a much higher proportion of patients with significant chest X-ray findings who had to be intubated [11, 14]. Because of the unavailability of ICU beds, all nonintubated patients in our series, with one exception, had to be treated in the ward; all cases were treated successfully. The one nonintubated patient who was transferred to an ICU was successfully treated with NIPPV. In alert patients who are breathing spontaneously, nasal continuous positive airway pressure has been reported to be beneficial, resulting in recruitment of atelectatic regions and reducing shunt [21]. To our knowledge there has been no report of NIPPV in patients with immersion injury.

Pneumonia is a serious and sometimes fatal complication of near-drowning [22]. Its incidence varies from 1.1 to 14.7% [11, 14]. According to Van Berkel et al. [14], intubation is a major risk factor (risk of pneumonia was 52% in intubated vs. 3% in nonintubated patients). Another factor that may be associated with pneumonia is immersion in grossly contaminated water [23]. Sometimes early infections often caused by uncommon pathogens (Aeromonas, fungi) have been reported in the context of immersion and aspiration of water. They can have a fulminant course, may be associated with bacteremia and sepsis, and have a high mortality [22, 24]. In our series, pulmonary infection was considered probable on clinical grounds in three nonintubated patients. The late appearance of pneumonia in our series suggests that it probably represents hospital-acquired infection and not the result of aspiration of microorganisms during immersion in seawater.

Three retrospective reviews have addressed the issue of prophylactic antibiotics in near-drowning and they have found no benefit [11, 14, 25]. Antibiotic prophylaxis is not encouraged, though cases of severe aspiration or near-drowning in heavily contaminated water may be possible exceptions [23, 24]. Nevertheless, all patients in our series received prophylactic antibiotics.

Our study confirms that noncomatose adult immersion victims who are not in need of intubation in the first 24 h have an excellent outcome after a relatively short hospitalization regardless of age. Patients who are not in a coma usually improve rapidly, without serious complications, in spite of the initial presence of often severe acute respiratory failure. When there is limited ICU bed availability, such patients can usually be treated successfully in the ward. A more protracted hospital stay may be expected in patients with confusion or a blunted conscience at presentation.

References

Quan L, Cummings P (2003) Characteristics of drowning by different age groups. Inj Prev 9:163–166. doi:10.1136/ip.9.2.163

Falk JL, Escowitz HE (2002) Submersion injuries in children and adults. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 23:47–55. doi:10.1055/s-2002-20588

Salomez F, Vincent JL (2004) Drowning: a review of epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment and prevention. Resuscitation 63:261–264. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.06.007

Bierens JJ, Knape JT, Gelissen HP (2002) Drowning. Curr Opin Crit Care 8:578–581. doi:10.1097/00075198-200212000-00016

Papa L, Hoelle R, Idris A (2005) Systematic review of definitions for drowning incidents. Resuscitation 65:255–258. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.11.030

Model JH (1981) Drown versus near-drown: a discussion of definitions. Crit Care Med 9:351–352

Conn AW, Barker GA (1984) Fresh water drowning and near drowning—an update. Can Anaesth Soc J 31(3):S38–S44

Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL (1994) The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 149:818–824

Ellis AA, Trent RB (1995) Hospitalization for near-drowning in California: incidence and costs. Am J Public Health 85:1115–1118

Spilzman D (1997) Near-drowning and drowning classification. A proposal to stratify mortality based on the analysis of 1831 cases. Chest 112:660–665. doi:10.1378/chest.112.3.660

Model JH, Graves SA, Ketover A (1976) Clinical course of 91 consecutive near-drowning victims. Chest 70:231–238. doi:10.1378/chest.70.2.231

Model JH, Graves SA, Kuck EJ (1980) Near-drowning correlation of level of consciousness and survival. Can Anaesth Soc J 27:211–215

Habib DM, Tecklenburg FW, Webb SA, Anas NG, Perkin RM (1996) Prediction of childhood drowning and near-drowning, morbidity and mortality. Pediatr Emerg Care 12:255–258. doi:10.1097/00006565-199608000-00005

Van Berkel M, Bierens JJLM, Lie RKL (1996) Pulmonary oedema, pneumonia and mortality in submersion victims; a retrospective study in 125 patients. Intensive Care Med 22:101–107. doi:10.1007/BF01720715

Cummings P, Quan L (1999) Trends in unintentional drowning. The role of alcohol and medical care. JAMA 281:2198–2202. doi:10.1001/jama.281.23.2198

Hunter TB, Whitehouse WM (1974) Fresh-water near-drowning: radiological aspects. Radiology 112:51–56

Al-Talafieh A, Al-Majali R, Al-Dehayat G (1999) Clinical, laboratory and X-ray findings of drowning and near drowning in the Golf of Aqaba. East Mediterr Health J 5:706–709

Rosenbaum HT, Thomson WL, Fuller RG (1964) Radiographic pulmonary changes in near-drowning. Radiology 83:306–313

DeNicola LK, Falk JL, Swanson ME (1997) Submersion injuries in children and adults. Crit Care Clin 13:447–451. doi:10.1016/S0749-0704(05)70325-0

Orlowski JP, Szpilman D (2001) Drowning. Rescue, resuscitation and reanimation. Pediatr Clin North Am 48:627–631. doi:10.1016/S0031-3955(05)70331-X

Dottorini M, Eslami A, Baglioni S (1996) Nasal-continuous positive airway pressure in the treatment of near-drowning in freshwater. Chest 110:1122–1124. doi:10.1378/chest.110.4.1122

Ender PT, Dolan MJ (1997) Pneumonia associated with near-drowning. Clin Infect Dis 25:896–902. doi:10.1086/515532

Simcock AD (1986) Treatment of near-drowning—a review of 130 cases. Anaesthesia 41:643–648. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1986.tb13062.x

Miyake M, Iga K, Izumi C, Miyagawa A, Kobashi Y, Konishi T (2000) Rapidly progressive pneumonia due to Aeromonas hydrophila shortly after near-drowning. Intern Med 39:1128–1130. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.39.1128

Oakes DD, Sherck JP, Maloney JR, Charters AC 3rd (1982) Prognosis and management of victims of near-drowning. J Trauma 22:544–549. doi:10.1097/00005373-198207000-00004

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gregorakos, L., Markou, N., Psalida, V. et al. Near-Drowning: Clinical Course of Lung Injury in Adults. Lung 187, 93–97 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-008-9132-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-008-9132-4