Abstract

Background

Though the same types of complication were found in both elective cesarean section (ElCS) and emergence cesarean section (EmCS), the aim of this study is to compare the rates of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality between ElCS and EmCS.

Methods

Full-text articles involved in the maternal and fetal complications and outcomes of ElCS and EmCS were searched in multiple database. Review Manager 5.0 was adopted for meta-analysis, sensitivity analysis, and bias analysis. Funnel plots and Egger’s tests were also applied with STATA 10.0 software to assess possible publication bias.

Results

Totally nine articles were included in this study. Among these articles, seven, three, and four studies were involved in the maternal complication, fetal complication, and fetal outcomes, respectively. The combined analyses showed that both rates of maternal complication and fetal complication in EmCS were higher than those in ElCS. The rates of infection, fever, UTI (urinary tract infection), wound dehiscence, DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation), and reoperation of postpartum women with EmCS were much higher than those with ElCS. Larger infant mortality rate of EmCS was also observed.

Conclusion

Emergency cesarean sections showed significantly more maternal and fetal complications and mortality than elective cesarean sections in this study. Certain plans should be worked out by obstetric practitioners to avoid the post-operative complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cesarean section (CS) is the worldwide process of pregnancy termination that delivers live or dead fetuses with an incision on the abdominal wall and uterine wall [1]. In the last decades, cesarean section has been performed to be a safe operation and improved the parturition outcome [2]. In America, the overall maternal mortality rate varies from 6 to 22 per 100,000 live births, and one-third or one half of the deaths attributed to the cesarean delivery that should be done [3]. CS has been rose in its frequency in many countries around the world [4, 5]. The previous studies have reported that the incidence of CS in the developed countries varies from 10 to 25%, while studies in India showed the cesarean rates varied between 8 and 36% [6, 7].

Though the rate of cesarean section has steadily increased and usually it is lifesaving, the procedure by itself carries risks and may increase the mortality and morbidity of mother and new born when compared to vaginal delivery [8,9,10]. Some studies have reported that the recovery time and intra- and post-operative complications of cesarean section, especially the emergency cesarean section (EmCS) [11, 12]. Postpartum maternal complications of cesarean sections include infection of wound and chest, blood transfusion complications, postpartum hemorrhage, burst abdomen, urinary tract infections (UTI), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), fever caused by infection, and other inflammation like endometritis, and mainly postpartum fetal complications consist of birth asphyxia, transient tachypnea of newborn (TTN), respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), sepsis, and soft tissue injury. Because of the inherent risks, World Health Organization stated that there is no justification for any region to have cesarean section rates higher than 10–15% [13]. Concerning these various and severe complications of pregnant women and fetuses, guidelines were established and implemented and cesarean section should be performed when some specific defined indications presented [14].

EmCS is a cesarean section that conducted in an emergence, and the indications consist of fetal distress, cephalopelvic disproportion, failure to induce labor, none progress of labor, and previous cesarean delivery [15, 16]. Another important reason of choosing cesarean section in present is the increase in maternal age [4]. Elective cesarean section (ElCS) is a procedure that is generally done around 39 weeks when the incidence of newborn with tachypnoea is much less. Several indications mentioned above are also observed in the indication of ElCS, and another main indication is the previous surgery of cesarean section. The relative risk for emergency CS was 1.7 times more than that of elective CS apart from antenatal complications and medical disorder [17]. ElCS may reduce the incidence of maternal morbidity and mortality, and it is not surprising that older mothers tend to automatically require elective cesarean section.

Although the types of complication in ElCS and EmCS were similar, several studies have reported that the rates of post-operative complications after ElCS and EmCS were different [18, 19], and the current study aims to synthetically establish comparisons of the main maternal and fetal complications and outcomes in two groups of pregnancy between ElCS and EmCS.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Related studies about the maternal and fetal complications and outcomes of ElCS and EmCS were comprehensive searched in multiple databases, including PubMed, Springer, EMBASE, Wiley-Blackwell, and China Journal Full-text Database. The systematic review and meta-analysis was undertaken with articles published from inception to October 2016 with all publication statuses (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress). The articles were searched independently and efficiently with the following keywords: (1) maternal OR fetal; (2) complication OR outcome; (3) elective cesarean section OR emergency cesarean section OR ElCS OR EmCS. All these terms were assembled with the connection symbol “AND” to search the articles related in the databases. To obtain more relevant studies and higher accuracy, the reference lists of each article we searched out should also be reviewed.

Citation selection

All the articles after the first screening were reviewed for the further selection. The titles and abstracts of these articles were screened independently and attentively. Then, the full text of the studies was obtained if the study was likely to be relevant.

The following inclusion criteria must be met in the citations included in this study:

-

1.

a randomized control trial study or a controlled clinical trial study;

-

2.

comparison of the morbidity and mortality between ElCS and EmCS;

-

3.

availability of full text.

Exclusion criteria:

-

1.

not a randomized study;

-

2.

studies on other means of pregnancy other than cesarean section;

-

3.

studies lacking outcome measures or comparable results.

The articles finally included were determined by these two investigators together. They checked whether the study was met the conditions presented above.

Data extraction

Two reviewers read the full text of the articles independently and extracted the relevant data of each study into coding sheets in Microsoft Excel software. In this study, the characteristics extracted consisted of the first author’s name, year of publication, year of onset, sample size (ElCS/EmCS), age range of pregnant woman, and outcome parameters. The extracted parameters included the maternal and fetal complications of ElCS and EmCS and infant mortality rate.

Statistical analysis

The meta-analyses were performed with the Review Manager 5.0 (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011) to estimate the difference of complication rates and infant mortality rates between ElCS and EmCS, and STATA 10.0 software was used to estimate the publication bias. Q statistics was used to reflect the levels of heterogeneity. A random-effect model was adopted when heterogeneity I 2 statistic >50%, which means that the moderate or high heterogeneity was obtained; otherwise, a fixed-effect model was chosen. We performed the sensitivity analysis and bias analysis to the quality of included articles, and risk of bias of the included studies was assessed with the following criterions: (1) random sequence generation, (2) allocation concealment, (3) blinding of participants and personnel, (4) blinding of outcome assessment, (5) incomplete outcome data, (6) selective reporting, and (7) other bias. In our studies, all parameters were binary variables and related risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was calculated. Funnel plots together with Egger’s tests were also applied to assess possible publication bias. P value <0.05 was considered that statistically significant was observed.

Results

Search results

A total of 1137 related titles and abstracts were initially searched out in electronic databases, and after an in-depth review, nine articles [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] eventually met all the inclusion criteria. The other 1128 articles were excluded for duplication, irrelevant studies, without a control group, incomplete data or comparison, other operations, reviews, or not a full text. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the study identification, inclusion, and exclusion that reflects the search process and the reasons of exclusion. Among these nine articles, seven were involved in the maternal complication of post-operation, three were involved in the fetal complication of post-operation, and four were involved in the fetal outcomes.

Characteristics of included studies

Details of the included articles are presented in Table 1. The first author’s name, year of publication, year of onset, sample size (ElCS/EmCS), age range of parturient woman, and sand outcome parameters of each study are shown in Table 1. All these articles were published from 2012 to 2016. The sample size ranges from 100 to 3217. Totally5019parturient women were included in these studies, and the puerperal in ElCS and EmCS group were 1390 and 3629, respectively.

Quality assessment

The bias table in the Review Manager 5.3 Tutorial was used to evaluate the risk of each study by applying the criteria of evaluating design-related bias. The risk of bias table in this study is present in Table 2. Due to the obvious differences between ElCS and EmCS, high risk of blinding of participants and personnel was existed for in the included studies.

Results of meta-analysis

Meta-analysis about the rate of maternal complication

Seven of nine included studies were involved in the maternal complication of post-operation. The forest plot for the rate of maternal complication in ElCS and EmCS group is shown in Fig. 2. All these seven studies showed the statistical difference of the rate of maternal complication between ElCS and EmCS group. In addition, the meta-analysis suggested that significant difference of the rate of maternal complication in ElCS and EmCS was observed [RR = 0.43, 95% CI (0.38, 0.48), P < 0.00001; P for heterogeneity = 0.68, I 2 = 0%].

Subgroup analyses about the rate of maternal complication

Subgroup analyses were preformed according to the types of complications. The major maternal complications in ElCS and EmCS were similar, including infection of wound and respiratory infection, fever, UTI, headache, wound dehiscence, DIC, and reoperation. The forest plot for subgroup analyses is shown in Fig. 3. The combined results demonstrated that the rates of infection, fever, UTI, wound dehiscence, DIC, and reoperation of EmCS were all much higher than those of ElCS [RR = 0.44, 95% CI (0.37, 0.53), P < 0.00001; RR = 0.29, 95% CI (0.19, 0.45), P < 0.00001; RR = 0.31, 95% CI (0.23, 0.41), P < 0.00001; RR = 0.67, 95% CI (0.48, 0.95), P = 0.02; RR = 0.34, 95% CI (0.17, 0.66), P = 0.001; RR = 0.44, 95% CI (0.21, 0.93), P = 0.03, respectively], while the rate of headache between ElCS and EmCS showed no difference [RR = 1.85, 95% CI (0.80, 4.30), P = 0.15].

Meta-analysis about the rate of fetal complication

These three included studies which involve in the fetal complication of post-operation are shown in Fig. 4. Despite Najam suggested that difference of the rate of fetal complication between ElCS and EmCS was not significant, the overall result indicated that the rate of fetal complication in EmCS was higher than that of ElCS [RR = 0.36, 95% CI (0.24, 0.55), P < 0.00001; P for heterogeneity = 0.28, I 2 = 22%].

Meta-analysis about the infant mortality rate

Four studies were involved in the fetal outcome, as shown in Fig. 5. Souksyna reported that the infant mortality rate in EmCS was similar to that of ElCS (P > 0.05), while the combined result suggested that the infant mortality rate of EmCS was also much larger than that of ElCS [RR = 0.16, 95% CI (0.10, 0.26), P < 0.00001; P for heterogeneity = 0.76, I 2 = 0%].

Bias analysis

According to the results above, low heterogeneities of meta-analyses about the rate of maternal complication, fetal complication, and infant mortality rate were observed (I 2 = 0, 22, and 0%, respectively), and fixed-effect models were chosen.

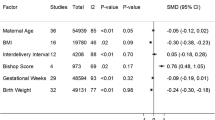

Funnel plots for the studies about the maternal complication, fetal complication, and fetal outcome were performed (Figs. 6, 7, 8), and the Egger’s tests of different parameters are presented in Table 3, which showed that no publication bias was observed in these meta-analyses (P > 0.05).

Discussion

Cesarean section rates have increased dramatically in recent years. Due to economical aspects in terms of health care budgets and customs, the cesarean rates vary in different countries, even in different regions. The CS rate of US was 32.8% in 2010 [27]. In India, cesarean rates ranged from 8 to 36% [28]. Cesarean section was used as a lifesaving operation of the mothers and because of the poor facilities and technology, the rate of complications reached 50 to 70% in the past decades. With the widely use of spectrum antibiotics, advanced blood transfusion facilities, and improved surgical techniques, the morbidity and mortality of mother and newborn with this procedure has come down considerably. Nowadays, cesarean section has been one of the most widely used procedures, even at some points, it has been abused. Though the mortality and morbidity of pregnant and fetuses is significantly decreased, it is still relatively high. The increasing rise of cesarean sections has attracted the attention of profession and public, and some gynecologists begin to discuss the necessity of cesarean section. WHO has recommended that cesarean section should only be done when it is necessary [29].

In this study, we compared that the rate of maternal and fetal complications between ElCS and EmCS for the previous has reported that elective cesarean section may reduce neonatal complications [30]. The articles included in our studies contained almost all types of maternal and fetal complications. The meta-analysis about the rate of maternal complication suggested that the morbidity of ElCS is quite lower than that of EmCS. The related risk of different complications varies. Except the headache of mother, other incidence of maternal complications including infection, fever, UTI, wound dehiscence, DIC, and reoperation is more common in EmCS compared with ElCS. These results may attribute to the longer preparation time, better surgical preparation of obstetricians, and also better condition of pregnant women. The headache of mother after the surgery may mainly be caused by anaesthesia, which is irrelevant to the types of cesarean section. Similarly, lower rate of fetal complication in elective cesarean sections was observed compared with emergency cesarean sections.

Except the complications of mother and newborn with cesarean section, fetal morbidity is another important issue. As a study in the developed country has reported, the infant mortality rate of cesarean sections is about 13 per 100,000, while the rate of vaginal birth is only 3.5 per 100,000, which is almost a quarter of the former [31]. Choate [32] et al. have suggested that compared with emergency cesarean section, elective CS has some advantages on fetal morbidity. In our studies, it has been shown that the risk of infant death is much greater with EmCS compared with ElCS.

Despite the fact that the same indications were observed in both elective and emergency groups, the proportions of symptoms are various. The indications of EmCS are usually emergent and critical, which would affect the occurrence of complications. In the results, the pure event rates of maternal complication were 23.3% (273/1172) in ElCS and 55.2% (1709/3094) in EmCS. The combined rates of fetal complication in ElCS and EmCS were 8.3% (22/265) and 20.2% (134/665), and rates of infant mortality were 1.7% (18/1035) and 9.8% (319/3248), respectively. Though the results showed the better outcomes of ElCS, the complications of both ElCS and EmCS were relatively high. One of the possible reasons was that some slight complications including headache were took into account. In addition, the week of gestation and decision-to-delivery interval (DDI) could also influence the prognosis. As long as the gestational age is more than 37 weeks or the DDI is less than 30 min, detrimental post-operative effects may be decreased, especially for fetuses [33,34,35].

In the present study, low heterogeneities of meta-analyses were obtained, and according to the funnel plots and Egger’s test, no publication bias was observed, which would support our results better. Although this study suggests that emergency cesarean sections showed significantly higher maternal and fetal complications than elective cesarean sections, there are some limitations that should be avoided. First, because of the particularity of the management, high risk of blinding of participants and personnel might be existed. The previous studies have pointed that ElCS may be more common in the urban, while EmCS may be more common in the rural [7]. Due to the better facilities and care in the hospital, the results may be influenced. Besides EmCS was usually applied in emergency situations, the status of the baby is bad originally, so it is not surprising that negative results are observed. In this study, we got some positive results, but some studies had relatively poor quality and a few studies included were published in internationally leading journals about obstetrics and gynecology, which indicates a need for further well-designed and prospective studies.

Conclusion

It was suggested that both elective cesarean section and emergency cesarean section cause certain complications to the mother and the fetuses. The incidences of maternal and fetal complications were relatively higher in EmCS than ElCS, and considerable care should be still required to provide and reduce the rates of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.

References

Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL et al (2005) Williams obstetrics, 22nd edn. McGraw-Hill Companies, New York

Sachs BP (2001) Vaginal birth after caesaren: a heath policy perspective. Clin Obstet Gynaecol 44:553–560

Khawaja NP, Yousaf T, Tayyeb R (2004) Analysis of caesarean delivery at a tertiary hospital in Pakistan. J Obstet Gynaecol 24:139–141

Landon MB, Hauth JC, Lenevo KL et al (2005) Maternal and perinatal outcome associated with a trial of labor after prior caesarean delivery. N England J Med 352:1718–1720

Chauhan S, Martin J, Henrichs C et al (2003) Maternal and perinatal complications with uterine rupture in 142,075 patients who attempted vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: a review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189:408–417

Keith Edmonds D (2008) Malpresentation, malposition, cephalopelvic disproportion and obstetric procedures. Blackwell publishing, London 17:311–325

Rao BK (1994) Global aspects of a rising caesarean section rate. In: Women’s health today: perspectives on current research and clinical practice. The proceedings of the XIV world congress of obstetrics and gynecology, Montreal, pp 59–64

Adashek JA, Peaceman AM, Lopez-Zeno JA et al (1993) Factors contributing to the increased cesarean birth rate in older parturient women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 169:936–940

Sowmya M, Dutta I (2014) Comparative Study of Neonatal outcome in Cesarean section done in referred cases vs Elective Cesarean delivery in a rural medical college hospital. J Evol Med Dent Sci 24:13993–13998

Hasssan S, Tariq S, Javaid MK (2008) Comparative analysis of problems encountered between patients of elective caesarean section and patient for whom elective caesarean section was planned but ended up in emergency. Professional Med J 15:211–215

Bergholt T, Stenderup JK, Vedsted-Jakobsen A et al (2003) Intraoperative surgical complication during cesarean section: an observational study of the incidence and risk factors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 82:251–256

Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA et al (2000) Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomized multicentre trial: term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet 356:1375–1383

World Health Organization (1985) Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet 2:436–437

Tampakoudis P, Assimakopoulos E, Grimbizis G et al (2004) Caesarean section rates and indications in Greece: data from a 24 year period in a teaching hospital. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 31:289–292

McCarthy FP, Rigg L, Cady L et al (2007) A new way of looking at Caesarean section births. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 47:316–320

Notzon FC, Cnattingius S, Bergsjø P et al (1994) Cesarean section delivery in the 1980s: international comparison by indication. Am J Obstet Gynecol 170:495–504

Belizán JM, Althabe F, Cafferata ML (2007) Health consequences of the increasing caesarean section rates. Epidemiology 18:485–486

Ghazi Asifa, Karim Farah, Hussain Ayesha Muhammad et al (2012) Maternal morbidity in emergency versus elective caesarean section at tertiary care hospital. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 24:10–13

Raees M, Yasmeen S, Jabeen S et al (2013) Maternal morbidity associated with emergency versus elective caesarean section. JPMI 27:55–62

Najam R, Sharma R (2013) Maternal and fetal outcomes in elective and emergency caesarean sections at a teaching hospital in North India. A retrospective study. J Adv Res Biolo Sci 5:5–9

SoukaynaBenzouina Mohamed El-mahdiBoubkraoui, Mrabet Mustapha et al (2016) Fetal outcome in emergency versus elective cesarean sections at Souissi Maternity Hospital, Rabat, Morocco. Pan Afr Med J 23:197

Suja Daniel M, Viswanathan BN Simi et al (2014) Comparison of fetal outcomes of emergency and elective caesarean sections in a teaching hospital in Kerala. Acad Med J India 2:32–36

Daniel Suja, ManjushaViswanathan Simi BN et al (2014) Study of maternal outcome of emergency and elective caesarean section in a semi-rural tertiary hospital. Natl J Med Res 4:14–18

Thakur V, Chiheriya H, Thakur A et al (2015) Study of maternal and fetal outcome in elective and emergency caesarean section. Int J Med Res Rev 3:1300–1305

Diana V, Tipandjan A (2016) Emergency and elective caesarean sections: comparison of maternal and fetal outcomes in a suburban tertiary care hospital in Puducherry. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 5:3060–3065

Zhang ZW (2016) The study of clinical comparisons with emergency cesarean and selective cesarean. China Foreign Med Treat 17:69–70

Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ (2013) Births: preliminary data for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep 62:1–17

Rao BK (1994) Global aspects of a rising caesarean section rate. Women’s health today: perspectives on current research and clinical practice. The proceedings of the XIV world congress of obstetrics and gynecology, Montreal, pp. 59–64

World Health Organization (2009) Monitoring emergency obstetric care: a handbook. Geneva. World Health Organization

Chongsuvivatwong V, Bachtiar H, Chowdhury ME et al (2010) Maternal and fetal mortality and complications associated with C/S deliveries in teaching hospitals in Asia. J Obstetric Gynaecol 36:45–51

ACO Obstetricians gynecologists (2014) Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 210:179–193

Choate JW, Lund CJ (1968) Emergency cesarean section: an analysis of maternal and fetal results in 177 operations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 100:703–715

Berlit S, Welzel G, Tuschy B et al (2013) Emergency caesarean section: risk factors for adverse neonatal outcome. Arch Gynecol Obstet 287:901–905

Paganelli S, Soncini E, Gargano G et al (2013) Retrospective analysis on the efficacy of corticosteroid prophylaxis prior to elective caesarean section to reduce neonatal respiratory complications at term of pregnancy: review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet 288:1223–1229

Hillemanns P, Hasbargen U, Strauss A et al (2003) Maternal and neonatal morbidity of emergency caesarean sections with a decision-to-delivery interval under 30 minutes: evidence from 10 years. Arch Gynecol Obstet 268:136–141

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XJY: protocol/project development and manuscript writing/editing. SSS: data collection or management and data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This study does not involve human participants or animals.

Informed consent

Informed consent is not required for this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, XJ., Sun, SS. Comparison of maternal and fetal complications in elective and emergency cesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 296, 503–512 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4445-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4445-2