Abstract

Summary

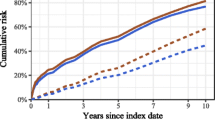

In Canada in 2008, based on current rates of fracture and mortality, a woman or man at age 50 years will have a projected lifetime risk of fracture of 12.1% and 4.6%, respectively, and 8.9% and 6.7% after incorporating declining rates of hip fracture and increases in longevity.

Introduction

In 1989, the lifetime risk of hip fractures in Canada was 14.0% (women) and 5.2% (men). Since then, there have been changes in rates of hip fracture and increased longevity. We update these estimates to 2008 adjusted for these trends, and in addition, we estimated the lifetime risk of first hip fracture.

Methods

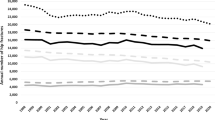

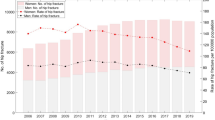

We used national administrative data from fiscal year April 1, 2007 to March 31, 2008 to identify all hip fractures in Canada. We estimated the crude lifetime risk of hip fracture for age 50 years to end of life using life tables. We projected lifetime risk incorporating national trends in hip fracture and increased longevity from Poisson regressions. Finally, we removed the percentage of second hip fractures to estimate the lifetime risk of first hip fracture.

Results

From April 1, 2007 to March 31, 2008, there were 21,687 hip fractures, 15,742 (72.6%) in women and 5,945 (27.4%) in men. For women and men, the crude lifetime risk was 12.1% (95%CI, 12.1, 12.2%) and 4.6% (95%CI, 4.5, 4.7%), respectively. When trends in mortality and hip fractures were both incorporated, the lifetime risk of hip fracture were 8.9% (95%CI, 2.3, 15.4%) and 6.7% (95%CI, 1.2, 12.2%). The lifetime risks for first hip fracture were 7.3% (95%CI, 0.8, 13.9%) and 6.2% (95%CI, 0.7, 11.7%).

Conclusions

The lifetime risk of hip fracture has fallen from 1989 to 2008 for women and men. Adjustments for trends in mortality and rates of hip fracture with removing second fractures produced non-significant differences in estimates

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Canadian Institute for Health Information, Health Indicators 2007 (Ottawa: CIHI, 2007)

Wiktorowicz ME, Goeree R, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, Papadimitropoulos E (2001) Economic implications of hip fracture: health service use, institutional care and cost in Canada. Osteoporos Int 12:271–278

Ioannidis G, Papaioannou A, Hopman WM, Akhtar-Danesh N, Anastassiades T, Pickard L, Kennedy CC, Prior JC, Olszynski WP, Davison KS, Goltzman D, Thabane L, Gafni A, Papadimitropoulos EA, Brown JP, Josse RG, Hanley DA, Adachi JD (2009) Relation between fractures and mortality: results from the Canadian multicentre osteoporosis study. CMAJ 181(5):265–271

Berry SD, Samelson EJ, Hannan MT, McLean RR, Lu M, Cupples LA, Shaffer ML, Beiser AL, Kelly-Hayes M, Kiel DP (2007) Second hip fracture in older men and women: the Framingham study. Arch Intern Med 167:1971–1976

Tarride JE, Hopkins R, Leslie WD, Papaioannou A, Morin S, Adachi JD, Bischof M, Goeree R (2010). The acute care costs of osteoporosis-related fractures in Canada. ISPOR 13th Annual European Congress, Prague, Czech Republic, November 6–9, 2010

Snelling A, Crespo C, Schaeffer M, Smith S, Walbourn L (2001) Modifiable and nonmodifiable factors associated with osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988–1994. J Womens Hlth Gend Based Med 10:57–65

Cummings SR, Melton LJ (2002) Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 359:1761–1767

Marks R (2010) Hip fracture epidemiological trends, outcomes, and risk factors, 1970–2009. Int J Gen Med 3:1–17

Goeree R, Blackhouse G, Adachi J (2006) Cost-effectiveness of alternative treatments for women with osteoporosis in Canada. Curr Med Res Opin 22(7):1425–1436

Schousboe JT (2008) Cost effectiveness of screen-and-treat strategies for low bone mineral density: how do we screen, who do we screen and who do we treat? Appl Health Econ Health Policy 6(1):1–18

Murray CJ, Evans DB, Acharya A, Baltussen RM (2000) Development of WHO guidelines on generalized cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ 9:235–251

Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oden A, Oglesby A (2002) International variations in hip fracture probabilities: implications for risk assessment. J Bone Miner Res 17:1237–1244

Levy AR, Mayo NE, Grimard G (1995) Rates of transcervical and peritrochanteric hip fractures in the province of Quebec, Canada, 1981–1992. Am J Epidemiol 142:428–436

Bacon WE, Maggi S, Looker A, Harris T, Nair C, Giaconi J, Hankanon R, Ho SC, Peffers KA, Torring O, Gass R, Gonzalez N (1996) International comparison of hip fracture rates in 1988–89. Osteoporos Int 6:69–75

Lofthus CM, Osnes EK, Falch JA et al (2001) Epidemiology of hip fractures in Oslo. Norway Bone 29:413–418

OECD health data 2010. by Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) & Institut de Recherche et d’Étude en Economie de la Santé (IRDES). Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [producer and distributor], 2010.

Leslie WD, O’Donnell S, Jean S et al (2009) Osteoporosis surveillance expert working group. Trends in hip fracture rates in Canada. JAMA 302(8):883–889

Nymark T, Lauritsen JM, Ovesen O et al (2006) Short time-frame from first to second hip fracture in the Funen County Hip Fracture Study. Osteoporos Int 17:1353–1357

Canadian Institute for Health Information, Data Quality Documentation, Discharge Abstract Database, 2008–2009—Executive Summary (Ottawa, Ont.: CIHI, 2009).

Juurlink D, Preyra C, Croxford R, Chong A, Austin P, Tu J, Laupacis A (2006) Canadian institute for health information discharge abstract database: a validation study. Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Toronto

World Health Organization (1992) International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth revision. World Health Organization, Geneva

Statistics Canada. Life expectancy at birth and at age 65 by sex and by geography, CANSIM, table 102–0512. 2007

Shepard J. Greene R.W. Sociology and You. Ohio: Glencoe McGraw-Hill. 2003. A-22.

Statistics Canada. Census of Canada 2008.

Oden A, Dawson A, Dere W, Johnell O, Jonsson B, Kanis JA (1999) Lifetime risk of hip fracture is underestimated. Osteoporos Int 8:599–603

Ryg J, Rejnmark L, Overgaard S, Brixen K, Vestergaard P (2009) Hip fracture patients at risk of second hip fracture: a nationwide population-based cohort study of 169,145 cases during 1977–2001. J Bone Miner Res 24:1299–1307

StataCorp. 2009. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP

Melton LJ, Chrischilles EA, Cooper C, Lane AW, Riggs BL (1992) How many women have osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 7:1005–1010

Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM et al (2009) Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA 302:1573–1579

Ziade N, Jougla E, Coste J (2009). Using vital statistics to estimate the population-level impact of osteoporotic fractures on mortality based on death certificates, with an application to France (2000–2004).BMC Public Health.17;9(1):344

Rosen CJ, Khosla S (2010) Placebo-controlled trials in osteoporosis—proceeding with caution. N Engl J Med 363:1365–1367

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johansson H et al (2009) FRAX and its applications to clinical practice. Bone 44:734–743

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A et al (2000) Long-term risk of osteoporotic fracture in Malmö. Osteoporos Int 11:669–674

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hopkins, R.B., Pullenayegum, E., Goeree, R. et al. Estimation of the lifetime risk of hip fracture for women and men in Canada. Osteoporos Int 23, 921–927 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1652-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1652-8